Piers Greville, Cartesian Algorithm, 2025, oil on cotton duck canvas, 182.88cm x 152.4cm.

Breakfast at Berghain

Philip Brophy

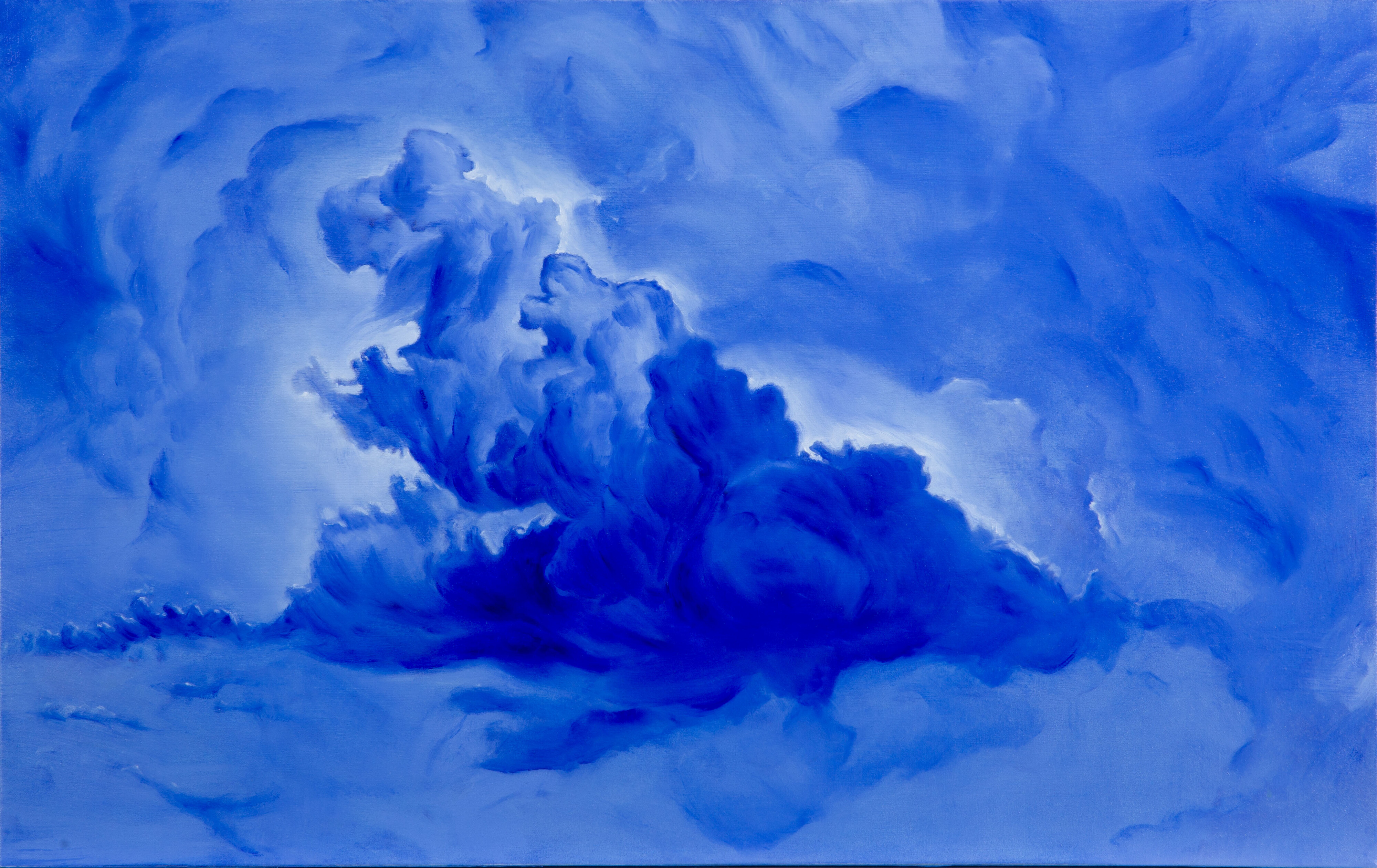

Somewhere within the cumulonimbiform clusters rendered in oils in Piers Greville’s exhibition at Magma Galleries, one can sense the tenebrous presence of two key Romantic paintings: Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819) and Eugène Delacroix’s The Barque of Dante (1822). The latter is directly quoted in a large Klein-like gamut of ultramarine tones, Breakfast at The Berghain (all works 2025). The former is excerpted in the smaller The Gold Gilt Dawn after Géricault. That is just two works from the fourteen paintings and eight studies on display. Most everything else depicts clouds devoid of land, people, and living things. The trick—perceptual, phenomenal, and ontological—is that the cloud paintings direct the viewer not to their Romantic resonance but to their vibrational energy, one that sails literally above everyone and everything.

This collection of Piers’s paintings could be aligned with a postmodern “pictures” arc, one that leads back to Mark Tansey. A somewhat forgotten yet crucial proponent of a type of textual illustrative practice, Tansey accentuates ironic counterpoint in his sourced imagery by overstating the grandeur of their Napoleonic capture (grand moments of great men, etc.). But revisiting Tansey’s work today can evidence that his oeuvre had little interest in appropriation or quotation and instead was concerned with a premonitional sense of catastrophe augured by civilised progress with all its extractive and exploitative industries. Clouds, oceans, storms, deserts, caves, and forests are continually deployed as Barbizon backdrops, setting stages for ignorant and disconnected humans and their Enlightenment follies of progress. See his Action Painting II (1984), The Raw and the Framed (1995), Wake (2003), and Recourse (2011). In his past few exhibitions of natural phenomena and their textures, Piers similarly works with a restricted pictorialism. He illustrates through skilled brushwork while circumnavigating realistic purpose. The narrowed palettes and delineated hues effect a pseudo-realism filtered through a palpable lens. This exhibition focuses on yellow and blue; decisively, green is never seen between.

Piers Greville, Breakfast At The Berghain, 2025, oil on cotton duck canvas, 182.88cm x 152.4cm.

Piers imports and extends Tansey’s practice, creating optical meringues that fold historical and Romantic stances with contemporary ways of sensing images of nature. In this sense, Piers is indicative of how “unpostmodern” everything is now. What I call “non-abstract” painting (others label it “representational”) for decades has escaped the arch posturing of those early postmodernists who thought they could hold an image at arm’s length and somehow freeze a through-line devoid of parallax distortion or palimpsestic composting. Piers’s painted clouds—a rich mix of insouciant mastery and unctuous style—constitute a textual signage that directs the viewer towards re-evaluating the enforced classical binaries of representational/abstract, natural/human, animate/inanimate.

Virgil Adrift levers the viewer into “reading” the loose forms of hero Virgil, guide Dante, and ferryman Phlegyas within the painting’s choreographed clouds. The more I studied the canvas, the more I thought I could see their shapes, but this feeling was overwhelmed by the sense of futility in attempting to formally parse figural substance from painterly mass. Yet this is the same experience I have had while studying The Barque of Dante numerous times in the Louvre. The cataclysmic stage of its performers—a proscenium of rippling poses, swirling fabrics, churning waters, billowing clouds—melts into a solidified atmosphere of elemental energies. Just as any element of the climate is but a transitional moment in energy transformation, all that is representational in The Barque of Dante sheds its Romantic guise and admits its contents to be a matter of temperature, moisture, and atmosphere. Virgil Adrift wedges the viewer into “unreading” the clouds.

Piers Greville, Virgil Adrift, 2025, oil on cotton duck canvas, 99cm x 61cm.

Neo-Classical, Napoleonic, History, and Romantic painting across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries often swirled and swilled cloudscapes to evoke heroic grandeur and connote heavenly presence (sentiments that Tansey has consistently mocked or subverted). Their conjoined co-option of natural forces framed their mortal subjects as godlike avatars, capable of affecting the weather through their emotional states and sheer will. This is not outrightly stated in the paintings’ narratives, but the inference is never absent: the panoramic clouds forecast a precipitous situation, just as they warn of approaching storms in real life.

Piers’s clouds riff on this effect, to which he brings bountiful allusions. Virgil Adrift made me think of one of Osamu Tezuka’s most famous images from his manga Jungle Emperor (1950–1954). On the third-last page of the five hundred pages of the manga’s serialization, a towering cloud formation is shaped to resemble the white lion Leo. It rises high, forcing the flatlands beneath the Ruwenzori Mountains bordering Uganda into a thin horizontal sliver slicing the manga page. Crossing the grassy tundra are two figures, rendered tiny against the magisterial sky. One is the explorer Higeoyaji, who has survived a journey from a snowstorm due to Leo having sacrificed himself so as to gift his own fur to Higeoyaji for his survival. The other is a white lion cub, Lune, whom Higeoyaji has by chance encountered and—sensing that Lune is a reincarnation of Leo—has gifted him the fur.

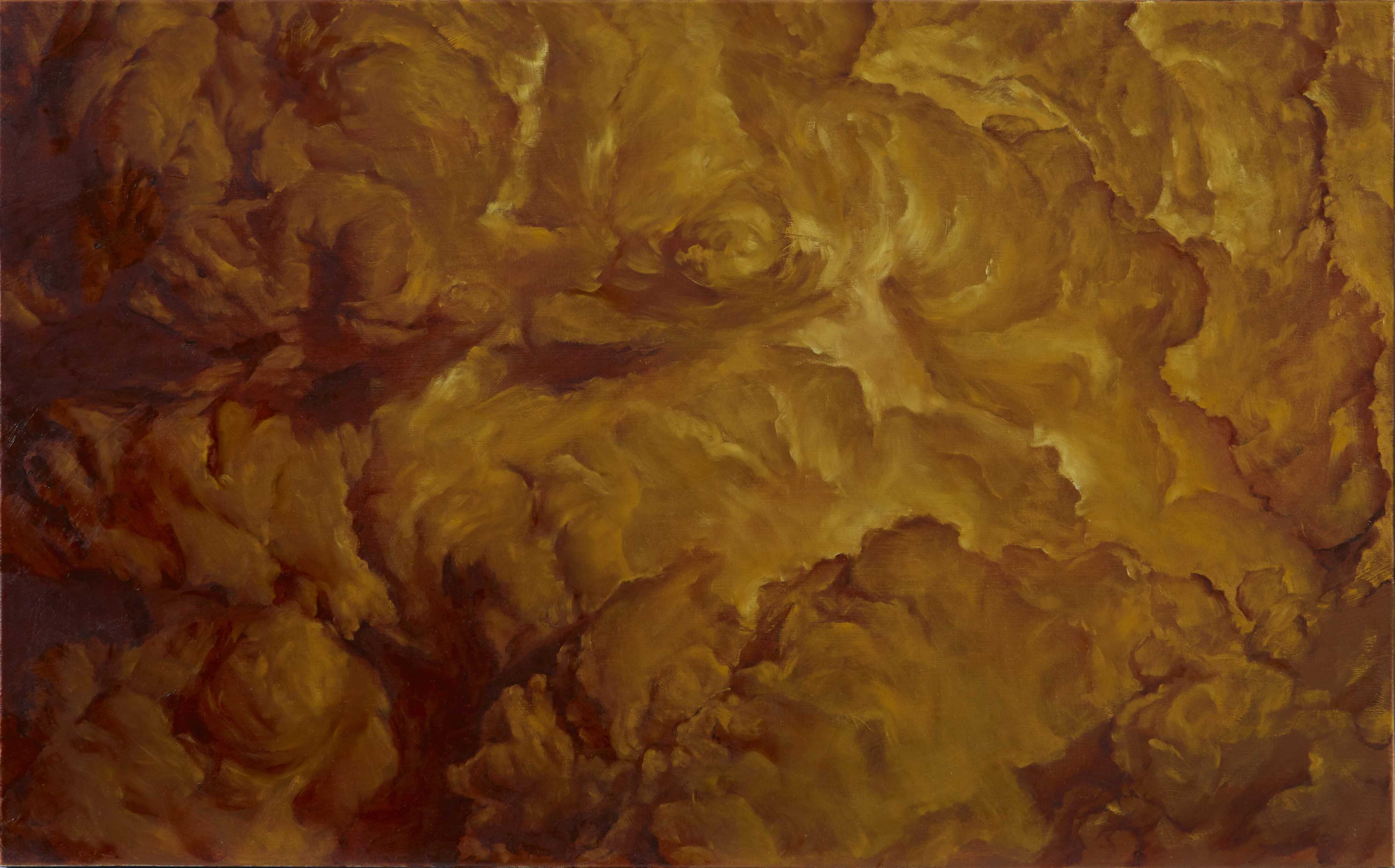

Piers Greville, Fortissimo Leitmotif, 2025, oil on cotton duck canvas, 99 x 61 cm.

That might be an obtuse corollary, but the shared “cloud-ness” between Delacroix and Tezuka lies in how nature is not a backdrop but an embodiment of the drama of its death-affected performers. This is especially so in the painterly realm of depiction. Figures become their surroundings; backgrounds inherit the figural substance of those depicted. Painters do not labour over backgrounds to verify laws of physics; they do so to stage their foregrounded contents, and in the process dress themselves more as theatre directors than painters.

Scanning Piers’s larger works like the mud-brown Fortissimo Leitmotif, the daffodil yellow Cartesian Algorithm, and the inky blue Uncertain Principles, I felt placed within a proscenium of tropospheric vistas: on stage, facing not the audience (me in the gallery) but the illusory “windows” opening onto the world. In an obvious sense, I had become Caspar David Friedrich’s rückenfigur, but at a deeper textual level, I was subsumed into the paintings’ mimetic vacua. And it is at this juncture that the idea of nature being greater than its human observation is driven to the viewer. Piers has assembled not canvases but a smattering of rickety rafts and barely buoyant barques that ferry their survivalist maps of clouds into the void of the white cube space. The exhibition is image-centric, but it also acknowledges how the natural world—the means by which it images itself through cartography and meteorology—is a stage.

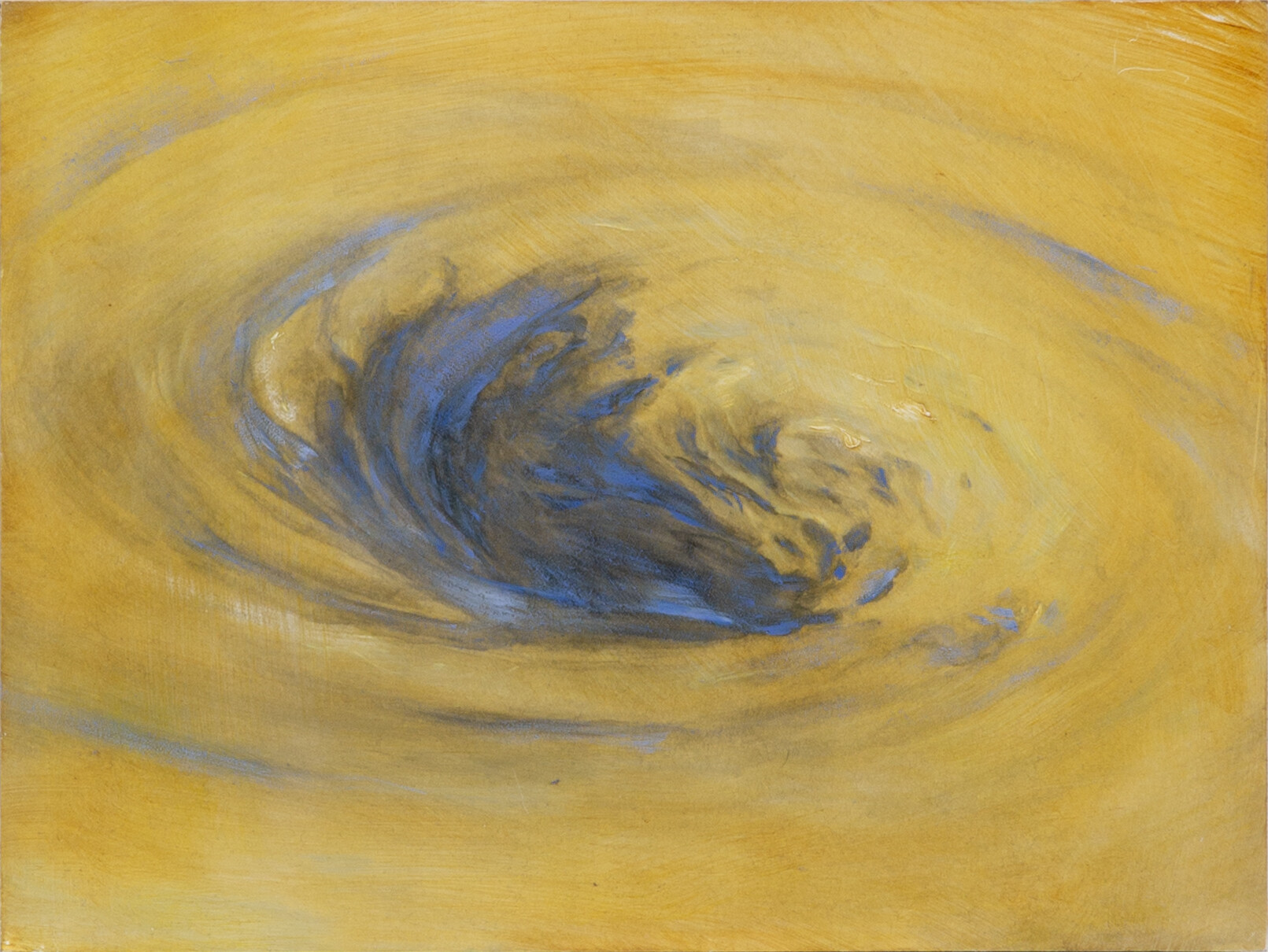

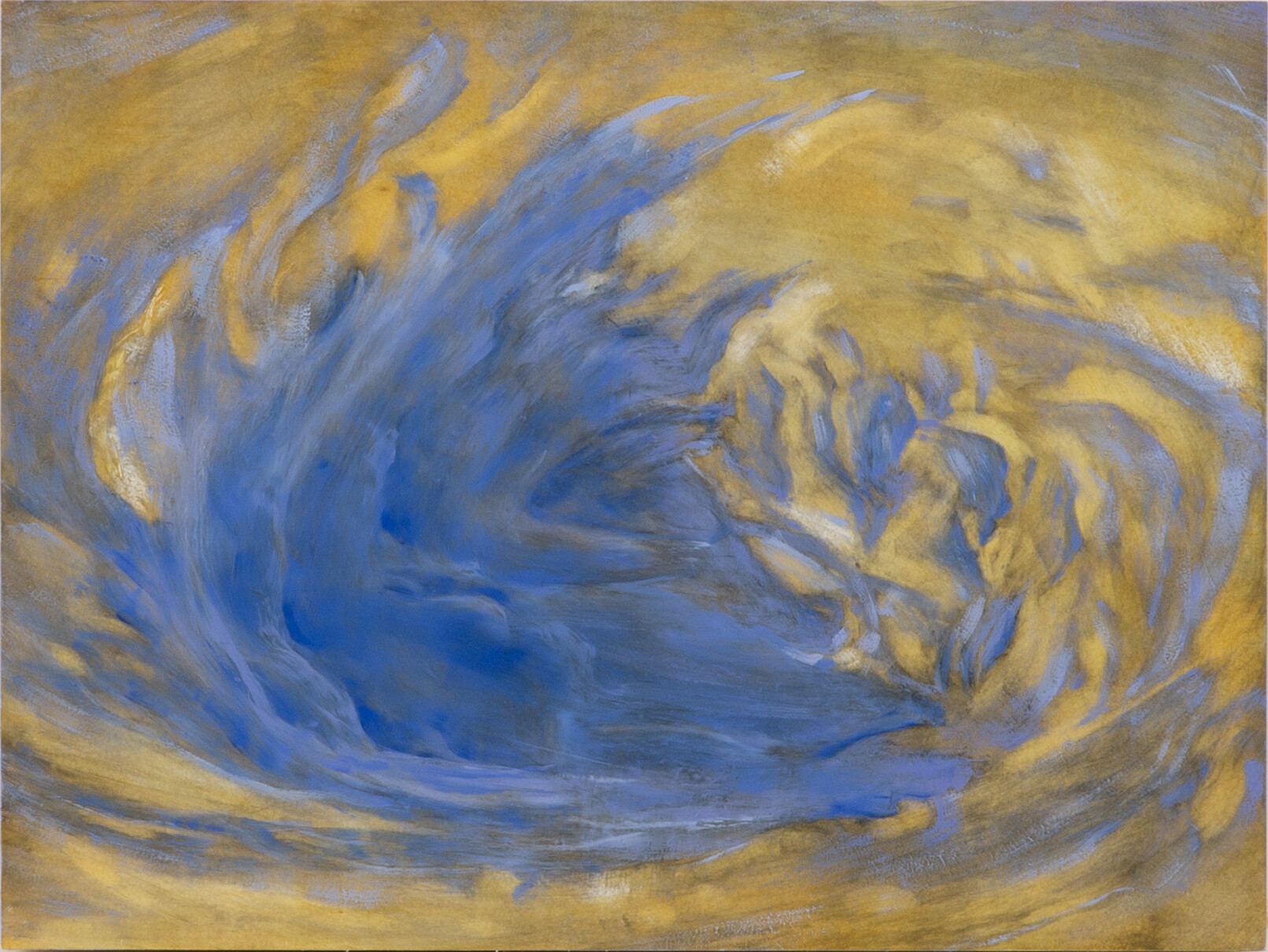

Piers Greville, Typhoon Yagi 1, 2025, oil on clay board, 30.5cm x 40.6cm.

Piers Greville, Typhoon Yagi 2, 2025, oil on clay board, 30.5cm x 40.6cm.

For those who insist on the monocled focus of contemporaneity, Piers’s cloudscapes will summon the dread of climate change. The first paintings one encounters in the exhibition are the pendant pair Typhoon Yagi 1 and Typhoon Yagi 2. Each is a gorgeous spiral of cornflower blue and sandy yellow, their arcs entwined in blurred greys. Their coils are instantly recognisable in an era of twenty-four-hour satellite animations that spin continually as superstorms and cyclones portend imminent disaster. To frame Piers’s paintings as some form of urgent global commentary, I feel, reduces his art—all art, in fact—to the dumb level of Guardian readers, whose interpretation of the complex cultural dynamics entailed in acts of imaging is sieved through people, politics, and power.

I interpret The Gold Gilt Dawn after Géricault as directing the viewer away from the gratuitous empathy enabled by contemporary art curation clinging to fabricated rafts for humanity. Piers’s small oil excludes the mortal flotsam of Géricault’s original work and, in the process, queries the use value of those depicted bodies in the first place. Few people would be discussing Géricault at dinner parties these days, but one can learn much from his embodied depiction of corporeal form. The Raft of the Medusa followed numerous preparatory oil studies of severed limbs and fragmented appendages. They are all muscle, obsessed with underlying energy rather than the skin of their appearance. Grounded in his era of lionised cavalrymen, public guillotines, and scandalous shipwrecks, Géricault painted flesh less as human signage and more as charnel organisms. (A fascinating exhibition, Visages de l’effroi–Violence et Fantastique de David à Delacroix at the Musée de la Vie Romantique in Paris in 2016 illuminated connections between the Empire/Republic flip-flopping and how French artists visualised human form).

Piers Greville, The Gold Gilt Dawn, after Géricault, 2025, oil on cotton duck canvas, 33cm x 33cm.

I can accept that viewers get emotional when fearfully pondering the fate of the planet. What I reject is the reparative urge to have the world service humancentric positivity. Piers’s exhibition arraigns its contents at the end of the spectrum of “the-world/image-of-the-world/painting-of-the-world/just-a-painting.” His stormscapes head in the opposite direction of—to cite the most obvious example of cloying, humanist hand-wringing—Bill Viola’s The Raft (2004) and its ostentatious “contemporisation” of Géricault’s ethical reportage. Breakfast at Berghain provided me not with yet more performative doom in topical art, but an exhilarating encounter with the elemental energies of painting converted into observational statements on the elemental energies of the world within which we swim and drown.

Philip Brophy writes on art among other things.