Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Featuring Hany Armanious, The Story of Art 2022. Collection the artist and Phillida Reid, London. Photo: Christian Capurro

Hany Armanious: Stone Soup

Chelsea Hopper

Hany Armanious: Stone Soup arrives at Buxton Contemporary as an exhibition that is both refreshingly surprising and, at times, almost perversely understated. This is paradoxical: many of the works are executed with such precision using silicone moulds and resin that they appear indistinguishable from what they mimic (I am genuinely floored by the autumn leaves in The Story of Art, 2022), yet what they mimic is often so visually negligible, such as debris, offcuts, or infrastructural leftovers, that the encounter can initially register as an anticlimax. Armanious applies a kind of sculptural virtuosity to the apparently worthless, unsettling expectations of what deserves representation.

Stone Soup was first staged in 2024 at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds; for the Buxton iteration, curators Charlotte Day and Laurence Sillers have expanded the Leeds display into a far more extensive survey. Just over seventy works sprawl across three gallery spaces on two levels, with some hiding in plain sight. Although the chronological range is wide (1998–2025), the exhibition is weighted decisively toward the last fifteen years, framing Armanious’s recent output not as a break but as an intensification of long-running material and conceptual concerns.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Featuring Hany Armanious, Empathy Chart 2009. Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, purchased with funds donated by Andrew and Cathy Cameron, 2009. Photo: Christian Capurro

Nostalgia arrives early in the exhibition, before Armanious’s strategies of misrecognition fully take hold. In Gallery 1, a work that looks a lot like a discarded pinboard is fixed to the wall (Empathy Chart, 2009). Opposite it leans, maybe, a paint-stained table (Depiction, 2012). These two facsimiles of drafting, making, casting feel less like sculpture than like the aftermath of school adolescence or a domestic workspace. The sight of paint splatters on a tabletop is strangely affective: I find myself thinking of the messiness of painting watery acrylics as a kid or watching my mother try her hand at painting outside on a similar-looking round glass table, where the same surface slowly accumulated stains and old paint marks over time. Armanious and I are being nostalgic together. Moving through into Gallery 2, things become more whimsical. Works such as Want (2023), a loose arrangement of what appear as sticks laid out like improvised makeshift wands, carry a distinctly childlike quality.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

David Foster Wallace once described David Lynch’s attention to the ordinary as a way of making the familiar feel unstable, as though everyday objects could become strange simply by being held in view for too long. Something similar happens in Stone Soup, though without dread. Instead, it feels like the work of a puckish trickster, turning everything he touches into resin. Hany Armanious’s works are not the objects themselves but casts, impressions that preserve form while evacuating function. What produces their aura is precisely this displacement—the sense of encountering a thing that looks recognisable, yet arrives as a fragile substitute, a double. This estrangement is heightened by the fact that so many of the works are placed directly on the gallery’s floor, refusing the plinth’s usual promise of elevation or clarity, and instead registering as things left behind, dropped, or temporarily abandoned.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

A sense of uncertainty sets in the longer I stay in the gallery. Several works initially read less like discrete sculptures than like remnants of installation or gallery upkeep, as though the exhibition is still in the process of being assembled. A small cluster of uneven pieces of Blu Tack (Logos, 2015) cling to the stairwell leading to Gallery 3; a pair of used paint trays (Luminous Solution, 2023) sit idly by; and at a distance what appear to be old drill holes and scuffs—which I later realise, via the room sheet, are actually a UV print (Realm, 2025)—blend seamlessly into the gallery’s existing patina. This deliberate ambiguity extends beyond the works themselves. It is so extreme that a gallery invigilator tells me they have to hide one of the chairs they’d usually sit on because visitors began to mistake it for a work; the same is true of the anti-fatigue standing mats placed near works around each gallery space when staff are not standing on them.

The ambiguity begins to feel less incidental than choreographed. Turning the corner into Gallery 3, I find Wow (2024)—a pair of intertwined coat hangers rendered in silver and gold—the illusion starts to feel almost scripted. I am reminded of an Absolutely Fabulous episode, where Eddie triumphantly presents Patsy with a series of new art acquisitions, including a mobile of wire coat hangers (“Hangers, sweetie! Hangers!”). The moment is funny because it names what Armanious’s exhibition repeatedly provokes: the uneasy, enduring question of whether art is something we recognise or something we are simply trained to believe in.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

That question is not rhetorical but material. Armanious’s works are often so painstakingly exact that they initially register less as sculptures than as things that have simply been relocated, moved from the world into the gallery without translation. What is striking is that this precision does not always hold. The illusion occasionally drops, and the viewer becomes aware of replication and its labour: the slight bubbly artificiality of resin, the way colour sits on the surface, or the subtle flattening that occurs when an object is remade rather than merely displayed. This is not a failure of craft, only a reminder that these objects are not readymades. Rather, they are reconstructions, copies whose authority depends on their closeness to an original that we never quite get to see.

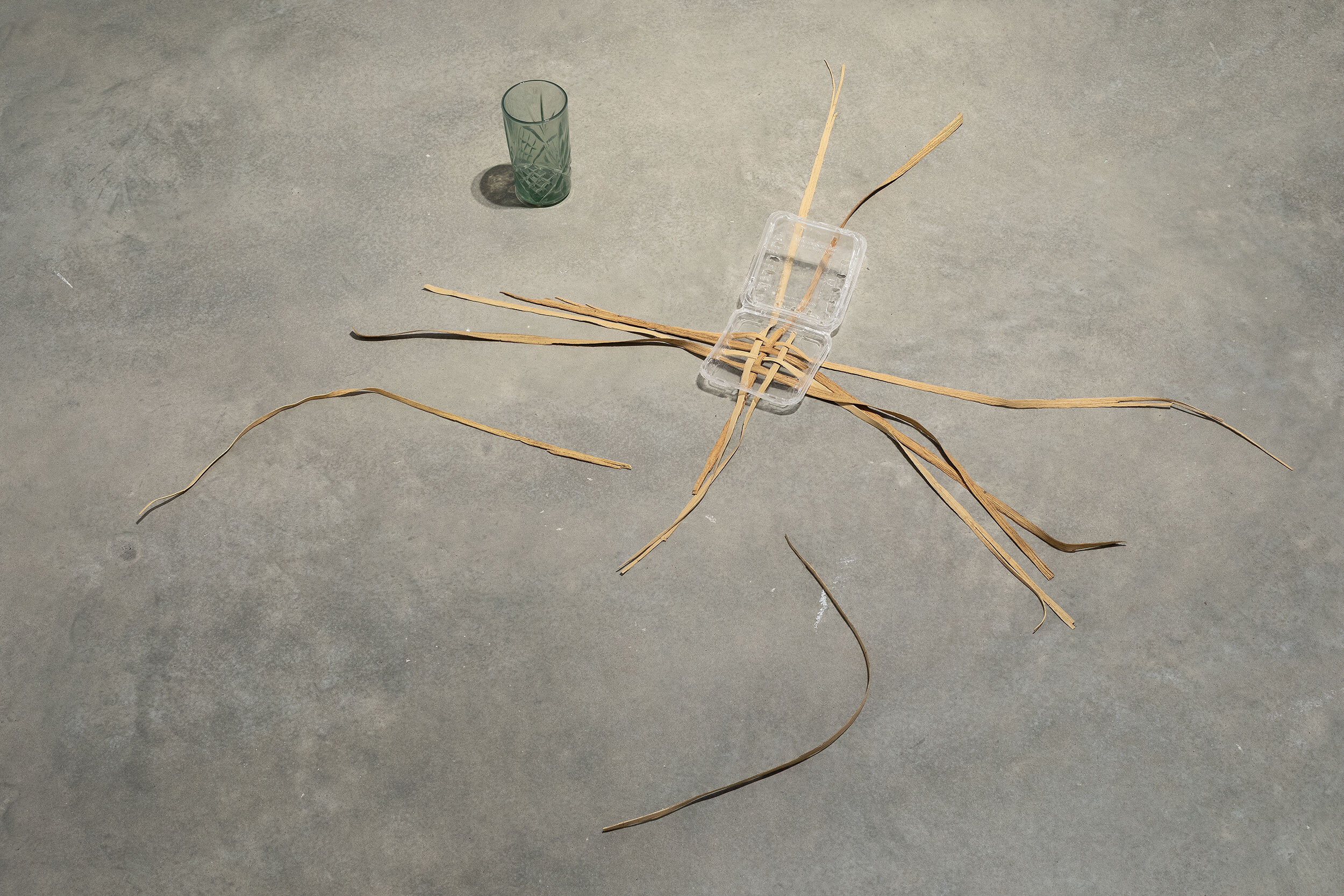

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Featuring Hany Armanious, Spooks 2024. Photo: Christian Capurro

Armanious relies heavily on the drama of a light composition, balancing just so. In Spooks (2024), a cluster of thin, twig-like lengths are threaded through a clear plastic punnet, the kind used for supermarket berries, before radiating outward across the floor. The careful spacing and alignment of forms make the composition feel as though it has settled into place of its own accord. The work’s restraint gives it an almost gravitational coherence, where its strangeness emerges less from what is depicted than from how elements are held in relation to one another.

Elsewhere, the limits of replication are more exposed. In Continuum (2025), a UV print of a loose smattering of apple stickers attached to the wall, the transfer looks comparatively fuzzy and inconsistent, particularly when set against Areopagitica (2025) found around the lifts, which I am convinced is black mould. Where the latter blends seamlessly into the building’s existing surfaces, nearly indistinguishable from dirt or decay, the former never quite convinces, its scale and finish drawing attention to the act of enlargement itself. By contrast, Universe (2021) is, in realist terms, uncannily persuasive. Here, a row of glittery animal stickers retains their visual authority, perhaps because the work operates so closely to the logic of an actual sticker, allowing the UV print to sit convincingly on the surface rather than announcing itself as an image of one. It is a small telling example of how exactness, scale, and placement can determine whether replication collapses or holds. Viewers play a game of verisimilitude that goes only two ways: I can believe! I cannot believe! An invigilator tells me that Armanious often finds objects exactly as they are and replicates them without alteration. I see this in the way the works feel both discovered and authored, as if formal composition itself is the invisible medium through which the ordinary becomes claimable as art.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Featuring Hany Armanious, Universe 2021 (detail). Photo: Christian Capurro

In co-curator Laurence Sillers’s catalogue essay, “In the Wake of Things,” Armanious’s casts are framed as “elevated versions of their originals,” described as a reversal of Walter Benjamin’s claim that mechanical reproduction diminishes the “aura” of the original. A claim that Armanious himself affirms. The suggestion is that Armanious’s recasting of the mundane intensifies the object’s singularity, turning the mass-produced into something newly precious. This reading feels slightly too neat. The works do not restore aura through authenticity or origin so much as re-stage it through display. Their surfaces feel preserved rather than enlivened, held in a state of suspended use, almost embalmed. Rather than undoing Benjamin, Armanious complicates him, revealing how easily aura can be re-staged through scarcity and the conditions of the gallery space.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

This dynamic becomes even clearer when attention shifts from institutional framing to the works on display, where questions of value and authorship surface in more overt ways. Upstairs in Gallery 3, Untitled (2015), a large UV-reactive dye work on cut-pile nylon carpet reproduces what appears to be a Texta scribble—reportedly made by the artist’s child—and enlarges it into a monumental field of bright blue gestural marks. On one level, the work reads as charmingly anti-heroic: the kind of drawing that might ordinarily end up in a rubbish bin is instead granted scale, permanence, and institutional seriousness. Still, it is difficult not to see how smartly this gesture collapses the distance between intimacy and cultural value. The scribble is not elevated because it is formally exceptional; it is elevated because it is framed as proximity to the artist, as a trace of private life made public through aesthetic permission. If Armanious’s practice repeatedly plays with the promise of anti-elitism—anyone could have found these objects, anyone could have made these marks—Untitled makes clear how quickly that premise is interrupted by the fact of authorship. The work is not simply a child’s drawing; it is a child’s drawing re-staged as contemporary art: translated into expensive material, expanded into a kind of abstract expressionist echo, and absorbed into the institutional logic that decides what counts as gesture and what counts as mess.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Featuring Hany Armanious, Sphinx, 2024, brass, pigmented polyurethane resin. Photo: Christian Capurro

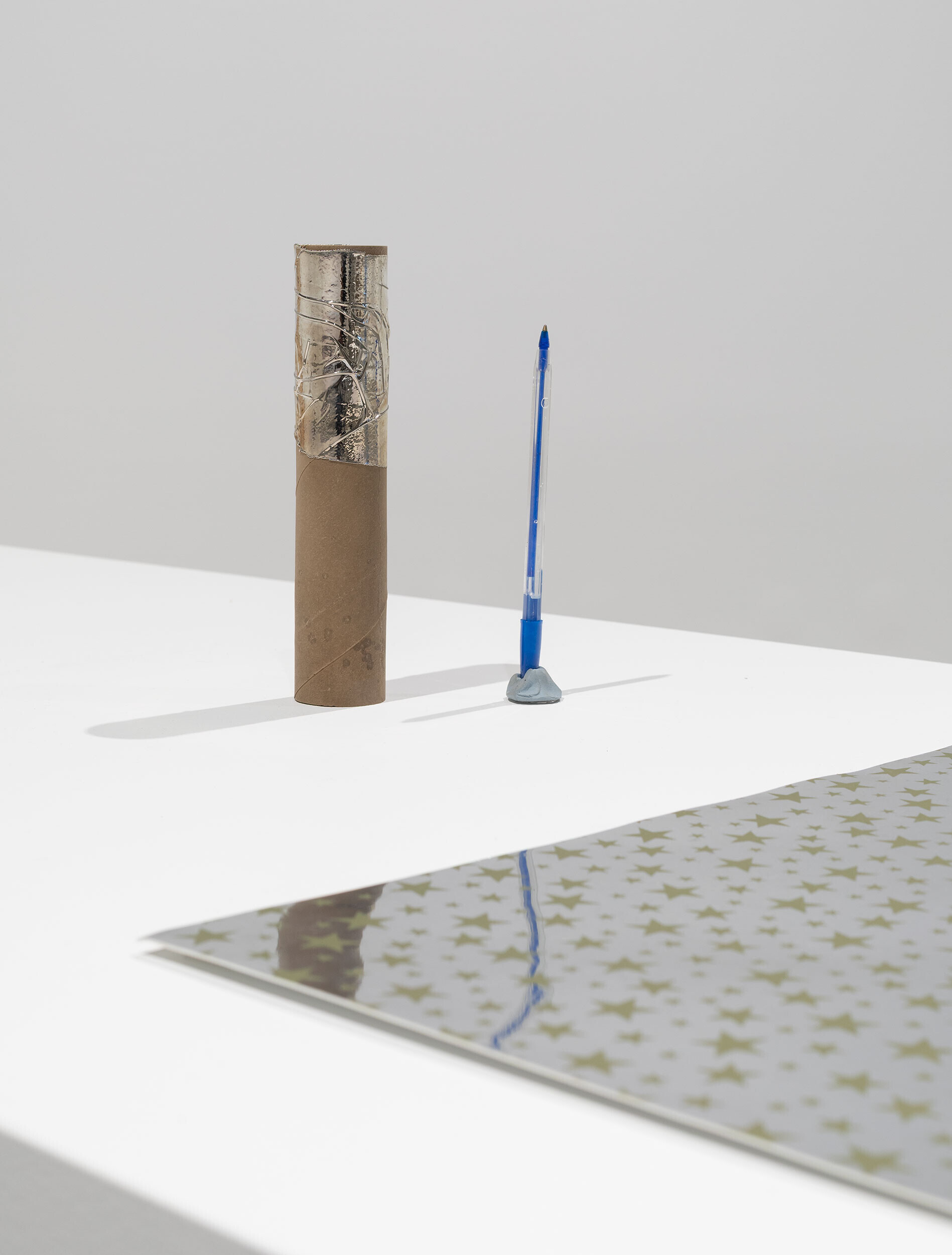

This tension becomes even harder to ignore in the exhibition’s own framing devices. With no wall labels or explanatory text, the room sheet becomes the primary interpretive structure: a sparse list of titles, dates, materials, and—crucially—provenance, noting the collections and lenders from which the works have come. Its extensive roll call of institutional and private holdings operates almost as a secondary curatorial gesture, quietly instructing the viewer as to how to regard what they are seeing. Faced with resin casts of sinks, light bulbs, containers, jars, trays, tables, and other domestic debris, the promise of anti-elitist subject matter is repeatedly interrupted by the reminder that these objects have already been absorbed into the institutional economy of contemporary art. An invigilator gleefully explains to me that one facsimile ballpoint pen has a real gold tip. Even so, the value of the art is not up for debate—it has already been decided elsewhere. In this way, the viewer is subtly pressured into treating the works as precious not because of what they are but because of where they have ended up.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Featuring Hany Armanious, Hollow Earth 2016. Courtesy the artist and Michael Lett, Auckland. Photo: Christian Capurro

Art history is also smuggled into the exhibition in ways that are easy to miss, as though Armanious is deliberately keeping the canon at arm’s length. It is difficult not to think of Fischli & Weiss, whose Equilibre series (1984–86) finds a clear affinity in Eulogy (2018). The work is composed of a rear-view mirror, a protractor, and a ladle, all cast in resin and fused into a static balancing act. It recalls Fischli & Weiss’s fascination with provisional arrangements, though here contingency is arrested rather than allowed to collapse. Elsewhere, references surface more plainly through titles: Weeping Woman borrows from Picasso, while Water Lillies (2018) cites Monet in both name and scale. A resin cast of a sink flipped upside down on a table reads as a sideways nod to Duchamp’s urinal, except here the readymade is painstakingly remade. These citations don’t function as reverent art-historical name-dropping, but rather a reminder that even the most mundane objects in the exhibition arrive saturated with cultural hierarchy, and that Armanious’s anti-elitist materials are never fully outside the museum’s long memory.

Installation view of Hany Armanious: Stone Soup, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro

Perhaps the exhibition’s most unsettling effect is the way it makes artistic permission feel both arbitrary and unavoidable. As Bob Dylan famously once said, “Everyone asks where these songs come from, Sylvie. But then you watch their faces, and they’re not asking where the songs come from. They’re asking why the songs didn’t come to them.” Armanious’s resin-cast objects oscillate this same uncomfortable truth: the materials are resolutely unglamorous—backless chairs, buckets, tools, containers, the overlooked infrastructure of domestic and working life—yet the transformation of these objects into art still carries the charge of cultural permission. Stone Soup toys with the promise of anti-elitism (anyone could recognise these things; anyone could have found them), while quietly exposing the persistence of elitism in the very act of artistic elevation: why this object, why this composition, why this artist? The works don’t resolve that contradiction so much as hold it open, insisting that the everyday is never just neutral matter but already entangled in systems of value, visibility, and taste. Like Dylan’s songs, Armanious’s objects provoke less awe at their origin than a faint, nagging resentment at their inevitability—as if what’s most unsettling is not that they exist, only that they feel like they should have already been ours to claim.

Chelsea Hopper is a curator and writer whose research interests include contemporary and modern photography and populism. She is the Art Director of Memo Magazine.