Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964 – 65)

I’m going to talk about Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964 – 65). But first, I’d like to detour from one exotic female body kneeling on the floor to another: Maria Martins’s Eighth Veil (1948). Hers is a life-size bronze of a limber, toned nude, seated on the ground, slumped as if she has collapsed from a kneeling position. Her supple legs bend outwards, high thighs and knees in front of her, the calves bending backwards. She steadies her posture by placing both arms straight with her palms touching the floor. She has turned her torso to her right, and her neck continues turning to position her head looking upwards toward something unseeable at her back. It’s a fascinating pose that withholds an unspoken narrative. It’s also testament to the unique perspective granted female form in the hands of a sculptress. Yet crowning the halting steely beauty of this body is a violently imploded head. Hairless and more resembling a bald knob than a head, it possesses a cranial shape with cheek bones and jaw line, but where facial features normally reside is a distressing cleft, sucking mouth, nose, and eyes into a frightening gash, and expelling a pulped aggregation of their components.

Exclusive to the Magazine

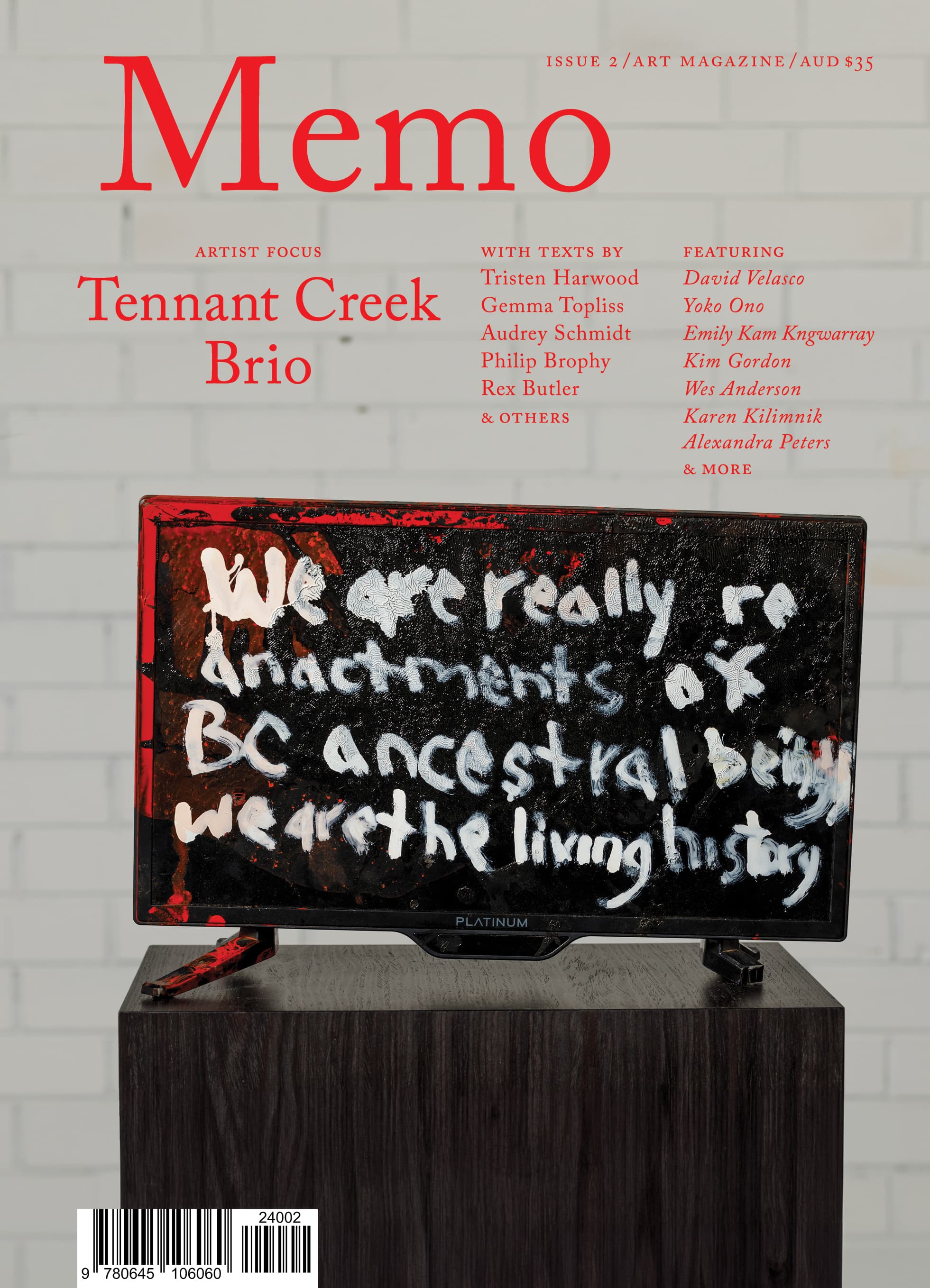

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964 – 65) by Philip Brophy is featured in full in Issue 2 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

Emily Kam Kngwarray’s art has been claimed, framed, and re-framed—by critics, curators, and institutions alike. But what remains of the singular, personal encounter with her work?

Melbourne’s art scene is fertile ground for Tall Poppy proliferation and carnage.

The dissemblant image can be understood as one deliberately distant from its subject, seemingly illogical in its association.