In Conversation: David Velasco and Kate Sutton

“There’s no path for the magazine to restore trust in its current ownership.” David Velasco and Kate Sutton reflect on the situation with Artforum and its Summer 2024 issue.

On 19 October 2023, Artforum published “An Open Letter from the Art Community to Cultural Organizations,” which calls for “an end to the killing and harming of all civilians, an immediate ceasefire, [and] the passage of humanitarian aid into Gaza.” Days later, Penske Media — which had acquired Artforum at the beginning of the year — fired editor-in-chief David Velasco. Nearly half the editorial staff, including editor Kate Sutton, resigned in protest of Velasco’s dismissal, and more than seven hundred artists and writers signed onto a boycott of Penske publications, which has since been ratified by the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI). On 14 March 2024, Artforum named Tina Rivers Ryan as editor-in-chief. No changes were made to the managerial team responsible for Velasco’s discharge. In this conversation, Velasco and Sutton reflect on the situation and Ryan’s debut issue for Summer 2024.

This article apperas in Issue 2 of Memo magazine. Order here.

***

Kate Sutton

It’s been more than six months since everything went down with Artforum, but the conversation still feels very unsettled, and just as relevant.

David Velasco

I’ve been talking to many Palestinian artists and scholars who’ve been approached to participate in some kind of package on “Israel / Palestine” in the Summer issue. Many didn’t know that there’s a boycott, or they didn’t know details of what happened at the magazine in October, just that I was fired, that some people quit. As time passes, the danger is that people forget, or they assume that things have been addressed or resolved.

KS

Well, it doesn’t help that a month or so back, the new editor-in-chief, Tina Rivers Ryan, issued a statement reaffirming the magazine as a place for free speech but neglecting to address that she has this position because the person who had it before her was fired for sharing a letter in support of Palestine. But it raises the question of what an ideal response would have been. Because I can fully imagine people looking at the Summer issue and saying, “Hey, they put a Palestinian artist on the cover, isn’t that great? Doesn’t that show that change has been effected at the magazine?”

DV

Palestinian voices were very much a part of the magazine before Penske. The cover of The Museum Now issue in Summer 2021 was an installation shot of Nida Sinnokrot’s work at the Palestinian Museum, which was tied to a conversation with then-director Adila Laïdi-Hanieh. We had major features on Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Jumana Manna in 2022. It’s not like suddenly Palestinian artists are now welcome.

What’s at stake is that at a critical moment in history, when editors chose to amplify the voices of thousands of artists and cultural workers who hoped to make a direct and immediate impact in Gaza, the publishers sided with a handful of advertisers. How are we to have confidence in the magazine’s owners when we know that this is how they will respond under pressure? So, yes, of course we want magazines to be elevating Palestinian voices — at this moment and always. What we don’t want is for this magazine to exploit Palestinian voices to whitewash the brand.

What’s an ideal response? For the magazine to be handed over to owners who could properly care for it. Because as I see it now, there’s no path for the magazine to restore trust in its current ownership.

KS

After the letter was published, many of the artist signees found themselves targeted, with people trying to sell their works, cancel their shows, or get them dropped from their galleries. It was the first time many of them had encountered that kind of coordinated campaign. But for others, especially internationally, that kind of pressure is normal. It’s great that the magazine wants to give exposure to Palestinian artists, but it seems they are only doing so in a moment when it feels convenient, when the risk is lower, when more of the global community is recognising the calamity of the Israeli occupation.

DV

When we published the open letter on 19 October, it was the eve of Israel’s ground invasion in Gaza, and we were hoping, very naively of course, that we might have even the tiniest impact on the conversation. It was professionally risky for the people who signed, and that risk is part of what gave it impact.

I’ve consistently been surprised by people who have told me, “Oh, well, the letter made people angry, so it wasn’t effective.” And I’m like, “No, that means it was effective.” When you’re working with a platform of this kind, you want to make use of it, you want things to have impact. Impact often looks like division. You create an opportunity for people to clarify where they stand.

Of course, risks also demand solidarity — you need people who are going to stand by the thing that they signed. Even if — especially if — there’s pressure. Every person who took their name off that list put everybody else at risk. They weakened the contract of solidarity. This isn’t about individuals. This isn’t about you and your career.

Returning to the boycott, there have been people who called to ask me how I would feel about them participating in the Summer issue. Feelings are facts, but they’re poor foundations. It doesn’t matter how I feel. I do have feelings about it, but that’s not what matters. What matters is that there are more than seven hundred people who signed on to a boycott of the magazine and other Penske publications. There’s a PACBI boycott, too. So this is about the solidarity and security of the people who are taking a stand. Everybody who contributes to the magazine right now is, in effect, putting those seven hundred people at risk. They’re saying fuck you.

Tina attempting — and failing, it seems — to put together an issue about Palestine at this stage and claiming that it’s in some way a continuation of the magazine’s commitment to activism and advocacy — that’s gaslighting. She’s using the magazine’s once valuable reputation to bait precarious artists. Having just read her first editor’s letter in the Summer issue, I’m amused that she can “acknowledge” that people have been punished for pro-Palestinian views, and yet she can’t acknowledge that the very reason she has her job is that I was fired for publishing a statement in support of Palestinian liberation. Tina’s letter is a shining example of how institutions cynically perform “acknowledgement” to obfuscate an issue.

KS

Meanwhile, the artists and writers who have boycotted the magazine are giving up access to a very powerful platform. Especially now, when there are so few opportunities for that level of critical discussion of art on a global scale.

DV

This is the very moment when refusal is most important. And in that way, it recalls the situation with the Whitney Biennial and Warren Kanders. As you know, in 2019, we commissioned and published a piece called “The Tear Gas Biennial” written by Tobi Haslett, Hannah Black, and Ciarán Finlayson. For context, Decolonize This Place and W.A.G.E. had attempted to mobilise a boycott before the Whitney Biennial opened, to protest the fact that the then-vice chairman of the Whitney Museum was Warren Kanders, the CEO of the weapons manufacturer Safariland, whose tear gas canisters were being used at the US border, against Black Lives Matter and pipeline protesters, and even in Palestine. There were protests at the museum, and Michael Rakowitz pulled his works in advance. These were critical first steps, but Kanders was still on the board.

A few months into the Biennial, Hannah, Tobi, and Ciarán decided to make a case for why artists should still boycott, even if they were already in the show. It’s such a skilful and moving argument, and one of the pieces that I’m most proud of publishing. Anybody who wants to think critically about how to do politics with art should read it. We published that and then, two days later, we published an open letter signed by four artists in the Biennial — Korakrit Arunanondchai, Meriem Bennani, Nicole Eisenman, and Nicholas Galanin — who decided to boycott the show. A few days later, Kanders resigned. I bring it up because of the points that Tobi and Hannah and Ciarán make. I will quote them, as they phrase it so beautifully:

We’ve heard, too, that the effort to politicize the Biennial amounts first, to racism, because it places an unfair burden on artists of color, who ought to be celebrated in this majority-minority Biennial, and second, an expression of class privilege, because “artists must eat.”This argument flies in the face of history and turns the very notions of strike and boycott on their heads — as if they were marks of luxury, rather than acts of struggle. Although in some cases made in good faith, this view promotes the reactionary fiction that marginalized or working-class people are the passive recipients of political activity as opposed to its main driver. Opportunities to collectively refuse are not unfair burdens but continuations of collective resistance.1

Yes, these actions have stakes. Yes, the stakes are often highest for the people who have the least. This isn’t a reason not to do it; this is just to recognise the facts of struggle. It’s an argument for the necessity of collective action.

KS

What was the response from the magazine at that time?

DV

This was something we commissioned and published. It originated with us, so there were discussions on the editorial side.

KS

Same with the Nan Goldin commission that sparked her P.A.I.N. campaign to hold the Sackler family accountable for their role in the opioid crisis, yes?

DV

Well, the Nan Goldin portfolio was part of my first issue as editor-in-chief, so I was involved in regular discussions with the publishers. And it was also in the print magazine, not only online like the “Tear Gas Biennial,” which meant there was more conversation in general. The publishers were valuable interlocutors, they had a strong history with the magazine, and I trusted their advice. With the Kanders piece, I recall talking to some of the publishers about running it, although we didn’t discuss the open letter from the artists. And, you know, I think that they were probably mindful that this would cause a stir, but they were also aware that this is what the magazine does. The publishing structure was also very different at that moment, with more general communication between editorial and publishing. But I want to be careful here, because I think the fact that I communicated with the publishers about, for instance, the Nan Goldin portfolio, has been used against me to suggest that this created an “editorial protocol” of how things will be handled, which is a mischaracterization.

KS

They used that exact phrasing as the reason for firing you, as if you breached a codified protocol. I find that there has been a lot of confusion of what the publishers’ role is and what editorial integrity actually means. I bring this up because in the wake of your firing, there was a counterargument from people saying, “Oh, well, you know, it’s also your responsibility to look out for the financial health of the magazine, so that the magazine survives” —

as if surviving were enough.

DV

Look, to be the editor-in-chief of a magazine like Artforum, especially at the time I was handed the reins, took a very political brain. It’s not like I wasn’t aware of the factors that were involved in survival. I know about survival. It’s just that economic survival was not first and foremost in my mind. Money comes and goes. It’s possible to have very little and then suddenly have more. That’s not the case with credibility.

I went to art fairs, probably more than any editor before me. I spent a lot of time with galleries. You do the best you can to position the magazine in such a way that it can do the work that it really needs to do, which, in my understanding, is to cultivate writers, to say something surprising about significant artists, to advance the politics of the Left and to make necessary critical interventions. And then you do the very constant work of persuading people that this is worth supporting, even if they’re not seeing any immediate benefits.

KS

There have been individuals who sought to discredit the editorial staff’s decision to use the platform to share an open letter that was coming from a community of artists, a community of our collaborators by posing the question: Was this “responsible”? Which, frankly, is an interesting way to frame a call for ceasefire and an end to genocide.

DV

“Responsibility” to me is a red herring.

I had very good reasons for doing what I did. I knew that the magazine, being a leftist publication at a significant historical juncture, needed to position itself, that it couldn’t just sit on the sidelines. I saw, at that point, how other publications were responding —

KS

— or not responding.

DV

Right. Yeah, there were a number of publications that were not responding, but the ones that I respected, and even a few that I had mixed feelings about, were responding. And some of them were responding in ways that I found very impressive. So I knew that we had to do something. I had conversations with nearly everyone on the editorial staff about what that could look like. We didn’t commission the letter. Originally, we were told that another publication was going to publish at the same time, but they dropped out, which is fine. When it arrived on my desk, it was signed by several thousand people, including more of our cover artists than I think I’ve ever seen on a single letter. It had a broad consensus of what I considered our critical constituents. And it had to be done quickly. It was not something that you could sit on for days. We had hours. And we made the right decision. I’m not sure what “protocols” the people running the show there are following now, but they’re facilitating some pretty weak decisions. And they’ve had all the time in the world.

KS

There was immediate impact when we published the letter. It wasn’t just the angry letters; there was so much support, flowing in from people who were grateful to see voices uplifted, which were not voices that were traditionally given that kind of platform.

DV

Absolutely.

KS

I mean, I mainly felt grief in the first few months, but I also recognised that my personal grief over what for me was the loss of a magazine that has meant so much in my life, and I know in yours as well — that was all against the backdrop of the sheer horror of what was going on in the news. It’s not hard to keep those things in perspective.

At the same time, these past few months, a lot of people have encouraged me to build something new. Not to be cynical, but I think there is a reason why so many magazines have shuttered or been sold off to slaughterhouses like Penske. There’s a reason why the conversations have been shaped the way that they’ve been shaped. I am struggling to feel optimism. There’s been a few attempts recently to found new publications, but it’s so clear that we need new models. I’m not just talking about, oh, we need to be online, interactive, etc. I think there was a moment when we bought into the idea that the space in which we could talk about art and politics was a safe space, that there was nothing really at risk, just a kind of performance of purportedly shared values tagged to notions of care or the Anthropocene, or whatever. And in some ways, we kind of forget that words can have risk, and they can have impact, like what we saw with the “Tear Gas Biennial.” And that risk and that impact is what makes this worth doing.

So I’m still grieving the loss of a space like that. And that’s not to dismiss the efforts of publications across the world that are trying to break these moulds. Offhand I think of Momus, which made the tough decision to look deeply at where it’s getting its money and really codify who it will and will not accept money from, even at a moment when its survival is not guaranteed. And they might not have the same kind of international profile, but it is incredibly inspiring to see people who, at this moment that has just been so extremely draining, can still find that energy to say, you know, we can build something different, there can be something that looks how we want it to look. That pays equitably, that recognises labour, that sets out these principles and sticks to them, even if it means it’s not comfortable in the short term or long term.

DV

There are huge gaps in the media landscape right now. Like massive gaps. And there are also really great publications out there doing incredible work. But the void left by Artforum is enormous. And I don’t think you can replicate that. And maybe that’s fine. Maybe it doesn’t need to be replicated. But, you know, if I were to start something, I would want to do it in a way that was very intentional, with the right partners.

KS

Maybe this should be the last point, but so many people have asked why the magazine needed to respond at all. And I think one of the things that has become crystal clear in my mind over these months is that I wouldn’t want to be part of a publication that didn’t say something. I wouldn’t want to be a part of a publication that only speaks out when it’s comfortable. Like we saw with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. No one ever took issue with us giving a very clear platform to Ukrainian artists with Yevgenia Belorusets’s diaries or Nikita Kadan’s portfolio for the magazine.

But I wouldn’t want to work where comfort is the priority. Comfort and survival, in a moment when we are looking at what survival means.

DV

Absolutely. You and I, we worked for the magazine that we wanted to work for. We built the magazine we wanted to build with colleagues we loved and admired. And when that magazine that we built conflicted with the magazine that the owners wanted, then that magazine ceased to exist. And we left. That’s the basics.

Notes

1 Hannah Black, Tobi Haslett, Ciarán Finlayson, “The Tear Gas Biennial,” Artforum, July 17, 2019.

Related

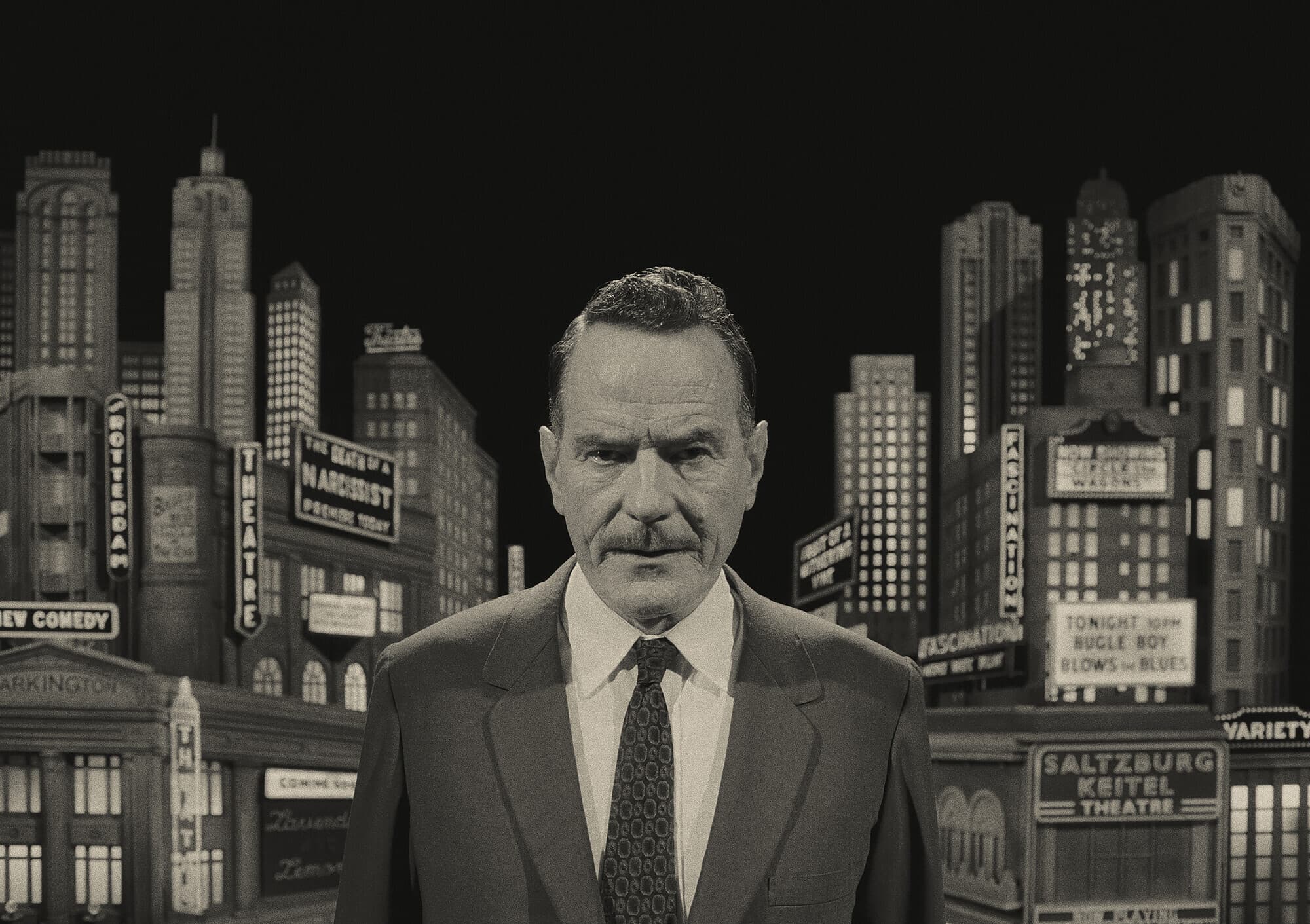

At a time when all these elements are easily replicated by AI and memed on social media, what is often called Anderson’s “twee” aesthetic continues to be derided as all style and no substance.

From Rhode Island School of Design‘s anti-commercial posturing to Gagosian’s prismatic salons, this fictional Anna Weyant chronicle exposes the brutal mechanics of ambition in contemporary art.