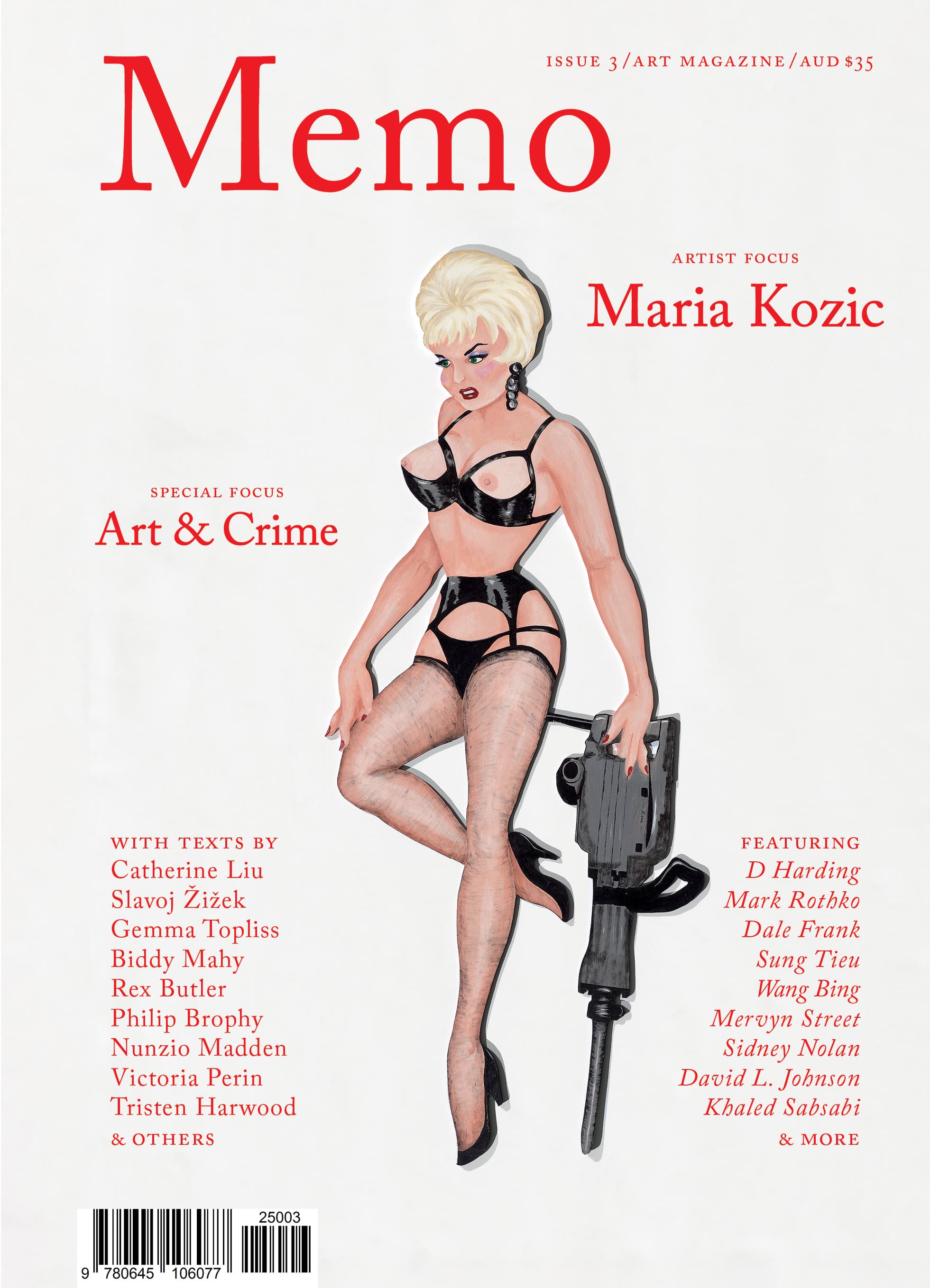

Problem Pop

Could there be a more vague, more abused, more assumed concept than “pop”? Sure, any single term or label behaves similarly, like a squirming worm impaled on a taxonomic hook, fishing for meaning in the Arts. Yet my reading of pop defaults to its negative origins, wherein lie both its cultural separation from the Arts, and its contextual importation by the Arts. I would argue that little has changed in the Arts in the past half century in terms of pop developing or transforming beyond those post-war battles staged between high and low cultures.

Exclusive to the Magazine

Problem Pop by Philip Brophy is featured in full in Issue 3 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

Shows about shows, documentation of documentaries, intertextual love affairs, and self-reflexive experiments ending in divorce. Caveh Zahedi revels in the real-life consequences of making your life your art.

Edie Duffy’s photorealism doesn’t just document—it distorts. Mining eBay’s throwaway images, she renders objects with a fixation that turns the banal into the surreal, collapsing nostalgia, obsolescence, and digital-age vertigo into a vision both unsettling and precise.