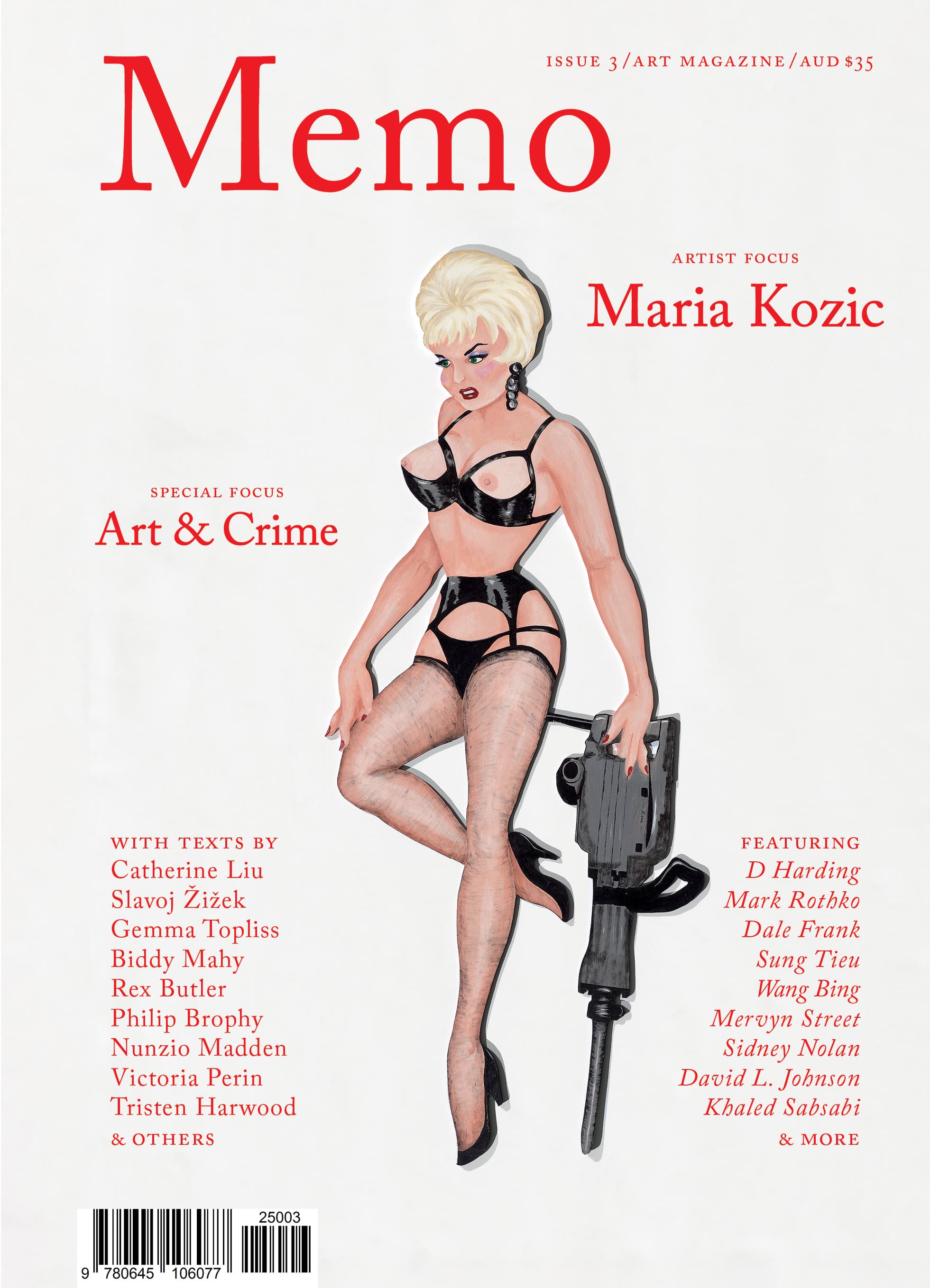

David L. Johnson

Artist David L. Johnson condenses centuries of enclosure into “Diggers,” repurposing hostile urban fixtures as provocations against privatisation, surveillance, and racial capitalism.

The enclosure of the commons—land traditionally held and used by the public—began in medieval England, and has continued ever since. In his 2014 book Stop, Thief!: The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance, American historian Peter Linebaugh contends that the enclosure and privatisation of the commons was inseparable from England’s industrialisation, as well as the development of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. In other words, enclosure played a foundational role in the rise of racial capitalism—a global system of value extraction and capital accumulation dependent on what abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes as “the state-sanctioned and/or legal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerabilities to premature death.” Linebaugh identifies three major waves of enclosure.

Exclusive to the Magazine

David L. Johnson by Dana Kopel is featured in full in Issue 3 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

Hollywood thinks it’s exposing the art world’s grift, but it’s just another con. From Velvet Buzzsaw to Picasso Baby, cinema keeps repackaging conceptual cringe as critique—while artists play along. If contemporary art is now just another film genre, it’s a bad one.

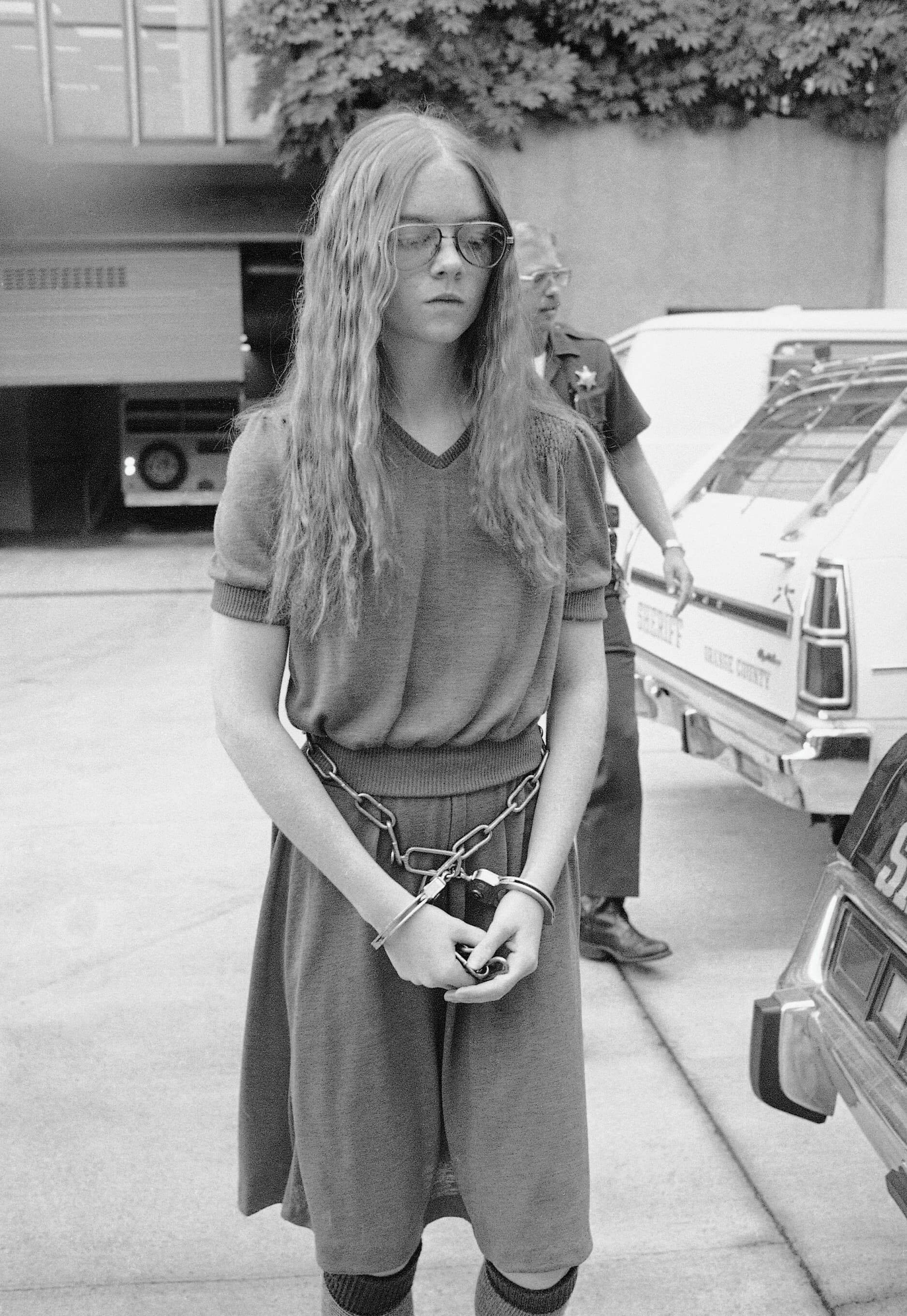

A little over a decade after Brenda Ann Spencer’s 1979 school shooting at Grover Cleveland Elementary School in San Diego, California, Karen Kilimnik used the crime as the premise for an artwork.

In an uneasy dialogue with Smithson’s modernist hubris, artist D Harding repatriates ochre, demanding an invitation to sites that colonial practice insidiously controls.