Janet Dawson, St George and the Dragon, 1964, oil on canvas,166 x 197 cm. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, gift of Ann Lewis AO 2011. © Janet Dawson.

Janet Dawson: Far Away, So Close

Victoria Perin

If the 90-year-old Janet Dawson ever experienced misery in her life, she did not tell her art about it. I drifted around the four rooms of her retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, temporarily convinced that life was about pulling your hair back in front of a blank canvas, heart full of verve. Dawson’s lack of worry or darkness elevates her above the designation of painter, and puts her into the territory of a guru. I want to sit at her feet and take notes. When I interviewed Dawson a few years ago she gave me a rock with interesting striations that she picked up in her driveway and obviously I have kept it. I don’t always look for cures in art, but I allow myself the delusion that Dawson could fix me.

The artist-critic James Gleeson saw some of this in 1964, calling her work “vibrant and spiritually untroubled.” This exhibition curated by Denise Mimmocchi shows how Gleeson’s description would become only more apt throughout Dawson’s life, with work starting from her student years in 1953 to the last work dated 2018. The exhibition catalogue, lovingly written and designed, doesn’t question the artist’s narrow fixation on pleasure, and breezes through six and a half decades. It is liberally peppered with the artist’s voice, in quotes full of gumption, like when she wrote home in 1960 to report about life in rural Italy: “A painter can live here without anyone thinking him queer or bohemian – I’m a farmer – I’m a painter – same thing.” We have no talk of hardships in these pages. Grapes heave on the vine.

A pre-established fan, I try to be objective, but I fall at the first critical hurdle. In room one, I can’t help liking the awkwardness of Dawson’s 1961 paintings. Although I see what could be called flaws—the inelegant halting of her stroke that doesn’t know how to end itself, the lumpiness of her gestural marks, a certain muddy fog that covers all—they are all charming problems. I enjoy these features in the three abstracts from her 1961 solo exhibition at Gallery A, all lent from private collections. Gallery A was then easily the coolest gallery in Melbourne. She so impressed gallerists Max Hutchinson and Clement Meadmore that they exhibited her, then hired her as a gallery manager.

Installation view of Janet Dawson: Far Away, So Close at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, featuring Viponds Tune (1961), Circle and Black Bar (1961) and Mannerist Painting with Various Devices (1964, reworked 1973), 19 July 2025 – 18 January 2026. Artworks © Janet Dawson, photo: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Jenni Carter.

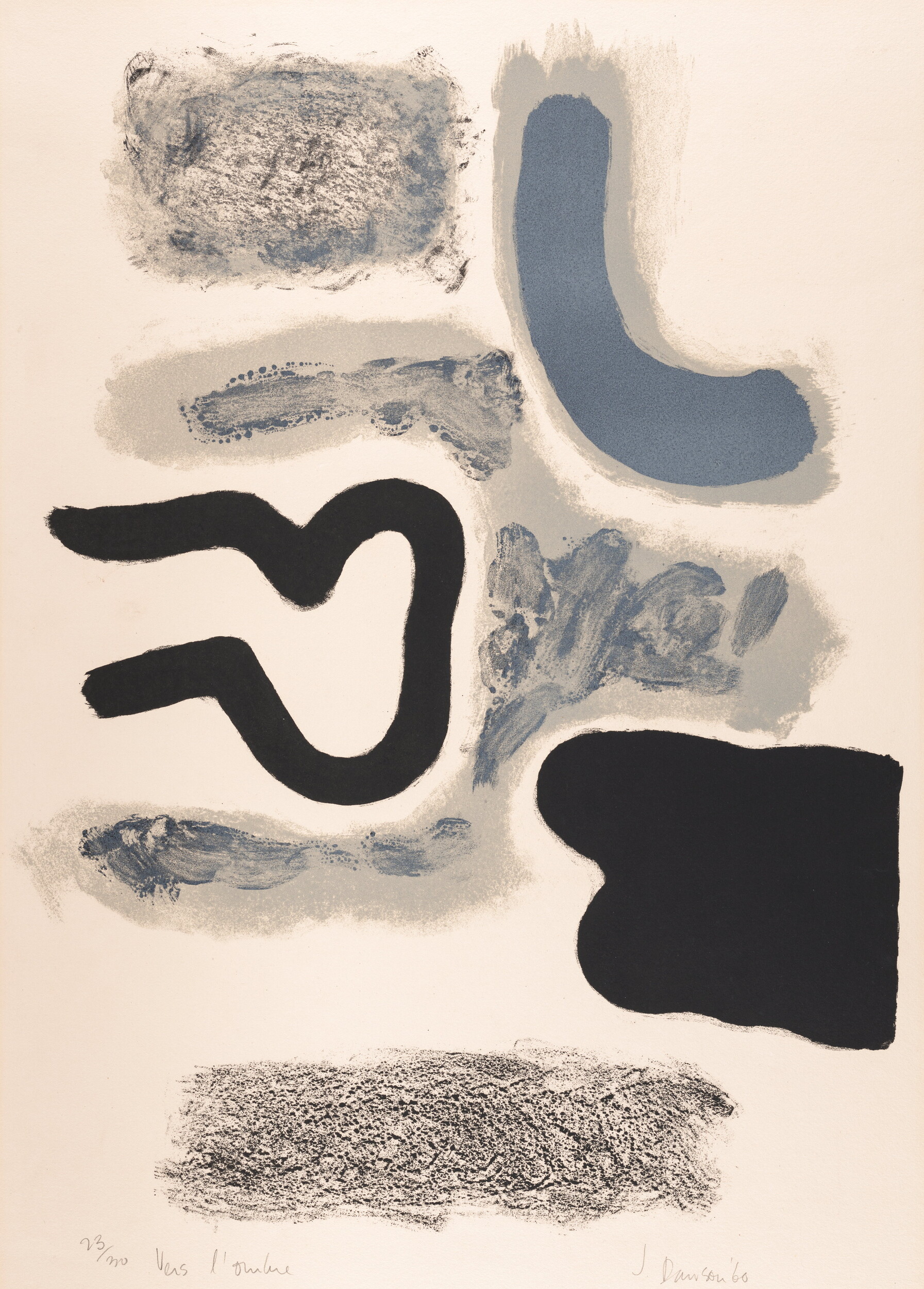

This early work is not a pure vision of paint. For the majority of 1960, Dawson apprenticed at Atelier Patris, a historically significant lithographic workshop in Paris. With her Paris prints hanging next to her early paintings, it appears that Dawson spent a few years trying to get paint to act like lithographic tusche, a greasy medium that makes effortlessly scumbled, liquid marks. Just a handful of years later, in the next room of the retrospective, we see that she quickly cleaned up her edges. By 1968, her paintings were hard-edged, but I miss the weird grey clouds she added all over the early work—every expanse an opportunity to insert a scuzzy little discolouration. Riffing off Wassily Kandinsky and Parisian painters like Pierre Soulange (whom she printed for), her first significant paintings are a mix between the jeune School of Paris crossed with a person who is proudly showing you a large and colourful bruise.

Her experience in Paris had made her by default a leading lithographer in Australia. She declined to work in the print room at RMIT (then the most important in the city), as she was put off by its art-school-amateurism. Instead, in 1963 she established Melbourne’s first fine art print atelier at Gallery A in South Yarra. The artist John Olsen is quoted as saying that she was “about the best printer in Australia”, when, really, she was the only person offering a professional fine art printing service to artists at the time.

Janet Dawson, Vers l’Ombre (Towards the Shadow), 1960, lithograph, printed in grey, blue and black ink, from three stones, 72.6 x 53.3 cm. Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1961. © Janet Dawson.

But ultimately, Dawson wanted to be a painter, not a printer. Viponds tune (1961) is named after the brand Viponds Paints, founded in Coburg in 1954. The artwork pays homage not to the paint’s quality or texture, but to its quantity. In Australia, Dawson couldn’t get oil paint in anything but small tin tubes—Viponds could, however, provide tubs with enough paint to cover a sizable canvas: 5.5 x 4.5 feet. After that the work grew even bigger. In these early years, Dawson was very influential in the Australian art scene. Along with Meadmore, her embrace of relatively large-scale abstract art helped transform Melbourne from the introverted figuration of The Antipodeans exhibition in 1959 to the bombast of the NGV’s 1968 showcase The Field. Yet her influence was not just due to the formal qualities of her abstraction, but also her resourcefulness and her personal ambition. At this time, the artist was thinking big and would not countenance provincial limitations. In most documentary photographs depicting Dawson painting, she is holding three or more paintbrushes at once.

Covering her European coming-of-age, the beginning of her association with Gallery A and her printing activity, the first room at AGNSW might represent Dawson’s early professional triumphs. But we don’t get much of an explanation about why she moved to Sydney in 1966, except for the pull of the non-objective scene, and the desire to escape the designation of “artists’ printer.” In truth, Melbourne had become a problem for Dawson. An exhibition more focused on trials and tribulations might have pulled out Dawson’s quote from a 1980 interview, when she regretted that, in the mid-1960s, “I was a very unpleasant person. I was horrible to my family, very hard and guarded and not a nice person to know at all. I tried to push every part of myself into my work and deny any sort of affection or love or emotional demands in my private life.” Becoming successful in a male-dominated scene, Dawson had gotten tough. Presented here as bold and powerful, her work in the early 1960s was equally driven by exasperation:

I was suffering as so many people do when they come back, from what I call “Travellers’ Gripes.” You get back and you find the world exactly as you left it and you feel as though you are drowning. And you really do go around and just kick every head you can see, out of fury and frustration … Eventually, I moved to another city, so I could begin again. I remember leaving Melbourne and thinking, that bloody city is full of all my failures and I want to leave them all behind me.

Though this quote is touched with pain, it is nice to hear Dawson whinge. So much more relatable than the triumphal one-note blast of Know-My-Name feminism.

If truth be told, the current decade might be the only time in Dawson’s career in which she is not prominent in Australia’s galleries. Even when she “retreated” in 1974 to renovate a hotel and farm in rural New South Wales, even when she didn’t have a commercial show for a decade between 1989 and 1998, candles were still lit for Dawson. She won prizes; her career timeline is littered with them, from the competitive National Gallery School Travelling Scholarship when she was 21, to the Archibald when she was 38, to an MBE when she was just 43. Before this show there have been surveys of her work in 1979, 1996, 2006, and 2012. But I suppose that when the AGNSW argues that “Despite prevailing respect from many in the art world, Dawson’s achievements are underacknowledged”, they really mean what does an artist have to do to be a household-name around here??

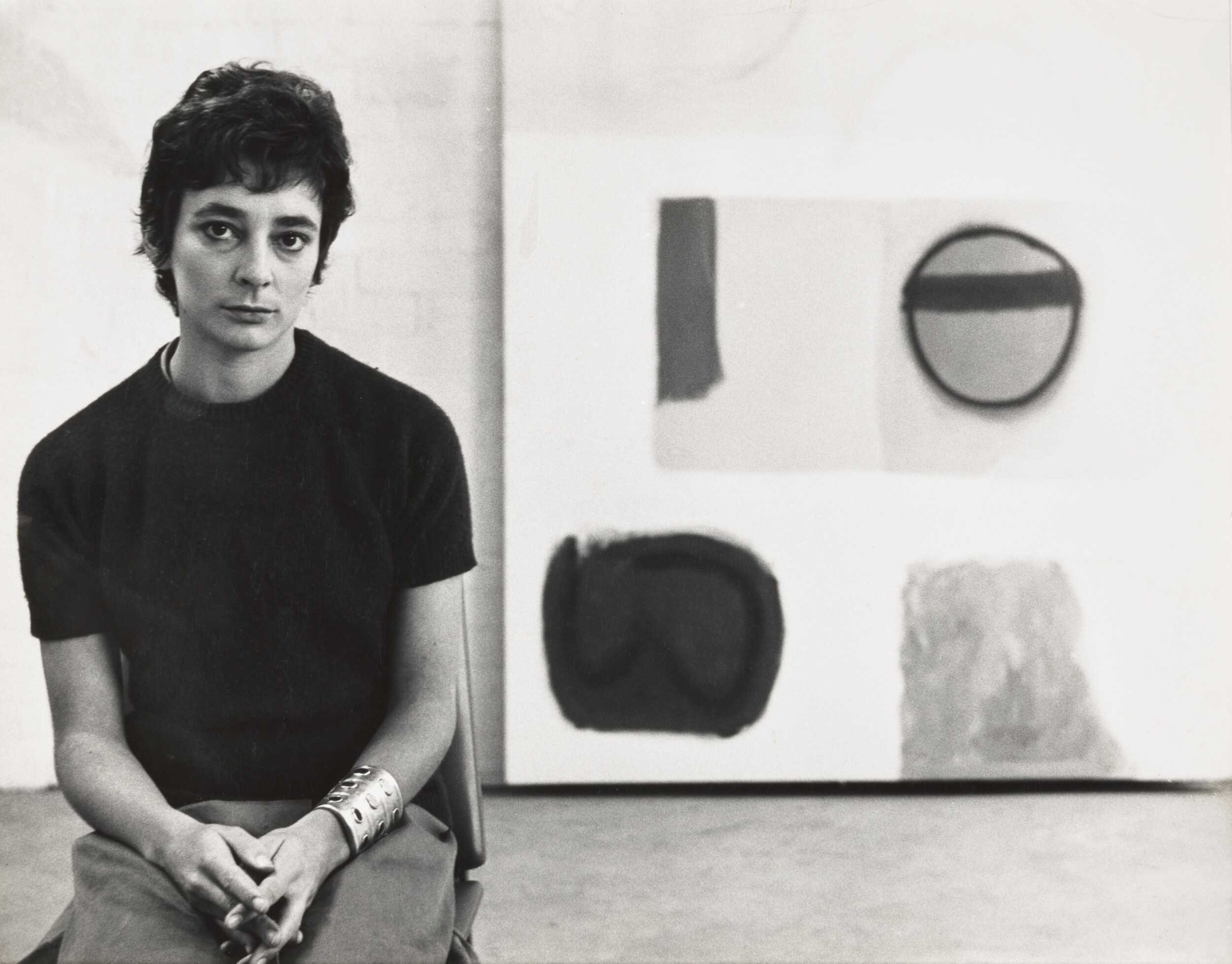

Janet Dawson with Circle and Black Bar (detail), 1961, Melbourne, 1961. Courtesy of Janet Dawson, photographer unknown.

Janet Dawson in her exhibition Far Away, So Close at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, July 2025. Artwork © Janet Dawson, photo: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Jenni Carter.

It seems this was a question that would have appealed to Dawson’s mother, Olga. I laughed when I read in the catalogue that Dawson was six when Olga, “arranged a meeting with Will Ashton, director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, for advice on the young Dawson’s artistic future.” “She was not much older” the catalogue continues, “when Olga set up a similar meeting with director Daryl Lindsay of the National Gallery of Victoria.” Olga’s manifesting worked. Sir Daryl might not have had a hand in it, but if people do know Janet Dawson today, it is from her inclusion, as one of the few woman participants, in the The Field. And perhaps visitors might instantly recognise Rollascape 2 (1968), a bravura painting from this exhibition that has been hung in prime position in the Art Gallery of Ballarat for many years. Here in room two, Rollascape 2 is a bulging headliner, a work that is so perfectly orange. It represents a moment when Dawson momentarily gives up on poly-chrome contrasts, shoots instead for unsullied lustre, and absolutely slam-dunks it.

Janet Dawson, Rollascape 2, 1968, synthetic paint on composition board,152 x 274.5 cm. The Collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat, purchased with the assistance of the Visual Arts/Craft Board, Australia Council, 1988. © Janet Dawson.

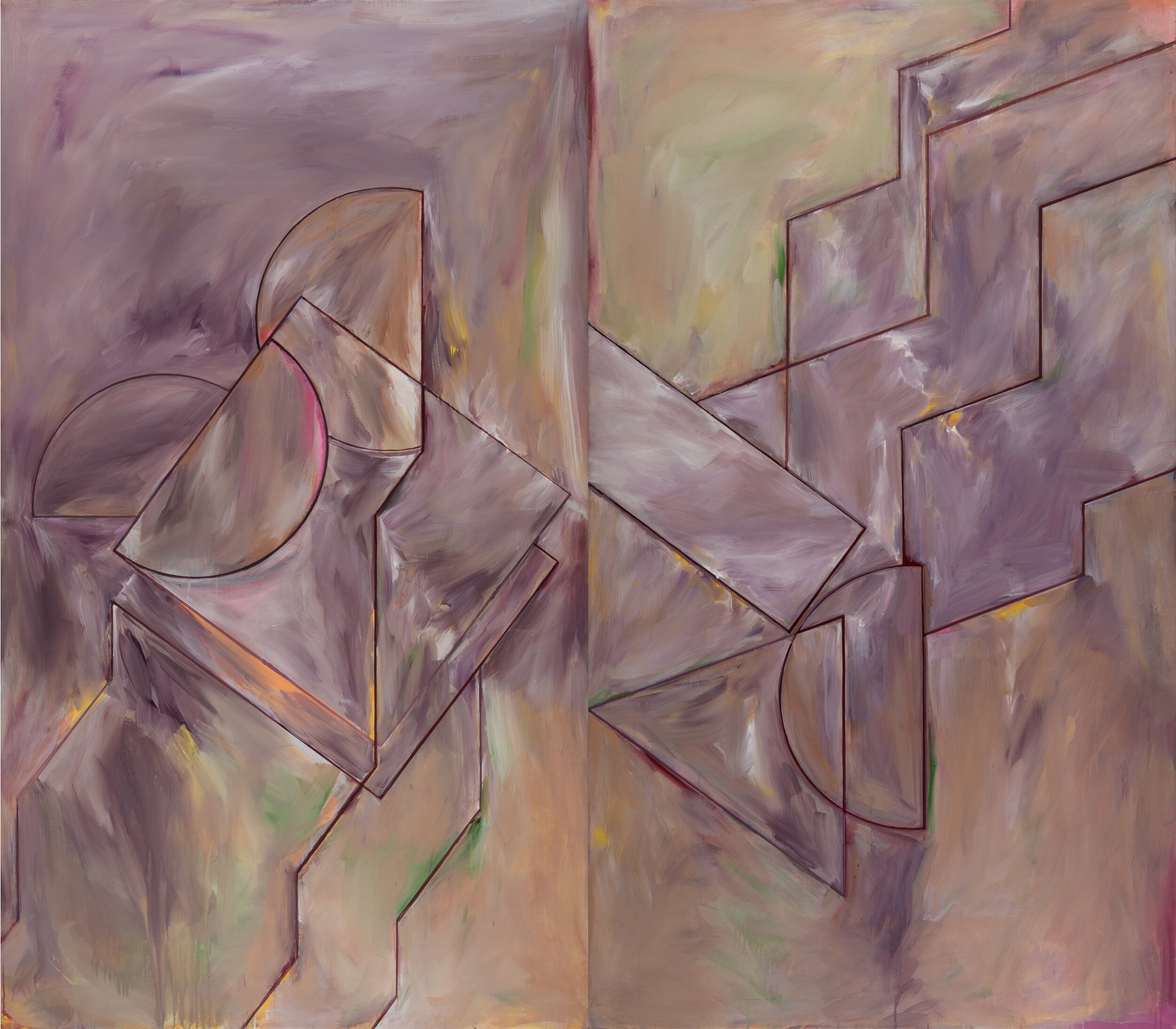

Once she leaves 1968’s hard-edge painting, which she seems to do immediately after The Field, all of Dawson’s magic gets sequestered in her use of highlights. Almost all the photographic reproductions you see of Dawson’s 1970s work (including the one below), can’t capture this and won’t do her justice. Adopting a confrontationally swampy aesthetic of impure brushstrokes, for a decade Dawson’s canvases become a bog of all the paints mixed together. The works in room three are best examined from the painter’s perspective (ten centimetres away from the surface), where the highlights are flame-like and each mysterious composition appears guided by guts alone.

Image 7: Janet Dawson, Old Cloudy Moons 1 and 2, 1979, diptych: synthetic polymer paint on bleached linen canvas, 213 x 244 cm overall. Macquarie University Art Collection, purchased Gallery A, 1979. © Janet Dawson.

In the 1970s, Dawson was looking at the landscape, ocean and sky, but thought that she still needed abstraction to convince us to look with her. From then on, there is a shift; resolutely from the 1980s to her late works Dawson makes representational images, some naturalistic, some otherworldly. Pedestrian art history would tell us that this move was regressive, and this could be half-heartedly dramatised as a fall from the avant-garde. Dawson weathered some of this critique at the time. Remembering a fellow artist declaring that she had betrayed abstraction, Dawson retorted, “Well, what is abstraction? It’s not a person, it’s not a country, it’s not a friend!” The straw man blows down. We skip into the fourth and final room, leaving the valourisation of abstraction behind us.

The 1980s are an absolute black hole here, with only two sketches making it out of the abyss. Scandalously, the AGNSW has not included Dawson’s 1986 portrait of her late husband, the dramatist Michael Boddy. Maybe Mimmocchi excluded it because it is massive (over two metres long) and would dominate any room. Gifted with the perfect body to play Falstaff, Boddy is rendered soft, frowning and lying on a couch naked except for his shoes and socks, while the head of his tiny penis sits roughly at the dead centre of the canvas. Pink and framed in orange pubic hair, the dick is so full of personality it took me several years to realise there was a dog in the picture too. Held in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, it is one of the great male nudes in Australian art.

Image 8: Janet Dawson, Scribble Rock Pomegranates, 1999, diptych: pastel on two sheets of primed paper on board, 33.5 x 80.4 cm. Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Arthur Boyd Acquisition Fund 1999. © Janet Dawson.

Nevertheless, this last room of the AGNSW show is overflowing with argument. Dawson emerged into the 1990s as a truly exquisite pastel artist. None of the loose abstraction of her middle-period could have prepared you for the detail she can record with a crayon—except of course if you remember that highlights are her wheelhouse, and 90% of the joy of pastels are in the highlights. A tumble of pomegranates, wiggling lettuce, two round and smooth ostrich eggs that look exactly like a beautiful butt. Roaming around her farm, Dawson takes up still life and delivers cornucopia after cornucopia.

Her real contention in this period, however, is with the moon. The moon and also the clouds are her signature late-style subjects; and her debate about naturalism is found in how she effortlessly captures these notoriously allusive muses.

Installation view of Janet Dawson: Far Away, So Close at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 19 July 2025 – 18 January 2026. Artworks © Janet Dawson, photo: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Jenni Carter.

Who doesn’t get choked up when, looking out the window of a plane, you breach through into the unbelievable terrain of clouds? Who doesn’t look at the full moon and rush to think with our pagan-brain, wow, I need a photo of this? The moon is hard to photograph, but we strongly desire pictures of it. That’s why Huawei and Samsung raced to give us Moon Modec and Space ZoomTM, two AI programs built into their smartphone cameras that fake high-resolution lunar images when you take photographs at night. All so we can simulate an iota of what it feels like to gaze at the moon! In a series of four gorgeous black pastels and some elegant tondo canvases, Dawson quietly demonstrates her skill in rendering the moon’s aura and the gravitas of clouds. Because we all lust after the moon, and because she renders its shifting appearance so acutely, the unique perspective of Janet Dawson recedes in these works. The artist becomes an every-man, a human transfixed. This is fine and good, and a thesis in itself. But in this room I missed some of Dawson’s more unusual later work, such as the Night Lights series from 2019, that demonstrate her particular, idiosyncratic artistic voice.

A memory reminds me that Dawson’s eye is far stranger than the final room in the AGNSW lets on. When I met the artist in 2019, she took me to a shed where some of her work is stored. We got side-tracked talking about a beloved sculpture that Dawson was keeping in there. She didn’t make it—rather, from what I can remember, she bought it at some cost from a sort of warehouse-store that sells tacky fibreglass decor. Roughly the height of an oversized lawn ornament, it was a white statuette of Mickey and Minnie Mouse dressed in Greco-Roman finery. Beyond kitsch. Completely faux marbled, Mickey had a laurel leaf crown, and they were both wearing togas. Dawson was besotted with it. She wanted to use it somehow in her art, but couldn’t figure out how. Maybe she would paint over them? Remembering the form now, the white, round heads and ears of Mickey and Minnie were clearly moon-forms. And Dawson was right, there was something perfect about them.

Janet Dawson, Morning Star, 1993, pastel on paper, 24.3 x 34.1 cm. Collection of Storry Walton AM. © Janet Dawson.

It’s the same feeling I get when I look at all of Dawson’s late-style works: whatever she turns her eye towards, there’s something perfect to look at. The world has beautiful things in it, of course, but there is such a thing as having a beautiful gaze too. When you have the skill that Dawson has, and your hands are full with brushes, your garden is abundant, you have a partner whom you love and you live under the crazy blue sky that you get on Ngunnawal land, who wouldn’t look on life exclusively as a pleasure? I don’t blame the AGNSW for focusing too tightly on the kind of Pollyanna delusion that this artist conjures. I too want to live in Dawson’s world, where bruises are breathtaking and life is always pomegranates, pomegranates, pomegranates.

Victoria Perin is an art historian and critic living in Naarm / Melbourne.