Nusra Latif Qureshi, Did you come here to find history?, 2009 (detail), digital print on clear film, 60 x 872 cm. Collection of the artist (exhibition print) © Nusra Latif Qureshi

Nusra Latif Qureshi: Birds in Far Pavilions

Amelia Langley

Nusra Latif Qureshi’s exhibition begins with a question: Did you come here to find history? This is the title of the work greeting viewers as they descend the escalator towards Qureshi’s exhibition: a mural of portraits that span art-historical crossroads. In the mural, profiles of Mughal emperors morph with icons of European Renaissance art and Qureshi’s own photo portrait. In one instance Qureshi’s face seems to merge almost entirely with one of the historical portraits—that of a nameless young circus performer, captured by the nineteenth-century Indian studio photographer Lala Deen Dayal. Qureshi takes control of her encounter with the viewer from the very start of Birds in Far Pavilions—while we attempt to dissect and identify these portraits, she peers back from within the work, fixing a steady and knowing gaze on us as we enter the exhibition. If viewers did come to the Gallery to find history, then her exhibition will offer no easy engagement with the past. Instead, the work documents her own experience of traversing histories of the past and present, East and West, and nobility and the everyday. Rather than constructing a linear narrative or a direct line to tradition, Qureshi presents a series of subjective and precarious engagements with a history of representation.

Qureshi’s encounter with art tradition is routed through her practice of musaviri painting. Musaviri is an Indo-Persian practice of miniature or manuscript-based painting that was introduced to Mughal India in the sixteenth century. These finely detailed narrative compositions evolved from Timurid illustrations of historical and mythological epic poetry. Under the Mughal court, musaviri painting came to incorporate distinct pictorial genres of portraiture and history painting.

As a young artist in Lahore, Pakistan, Qureshi closely engaged with these art traditions while studying musaviri painting at the National College of the Arts. Part of a generation of contemporary artists who reclaimed these disappearing practices, she began to play with and deconstruct the formal conventions of the manuscript page, in tandem with centralising female subjects in a historically patriarchal art tradition. In Birds in Far Pavilions, Qureshi’s work is in fact accompanied by historical Mughal and Pahari musaviri paintings from the AGNSW collection.

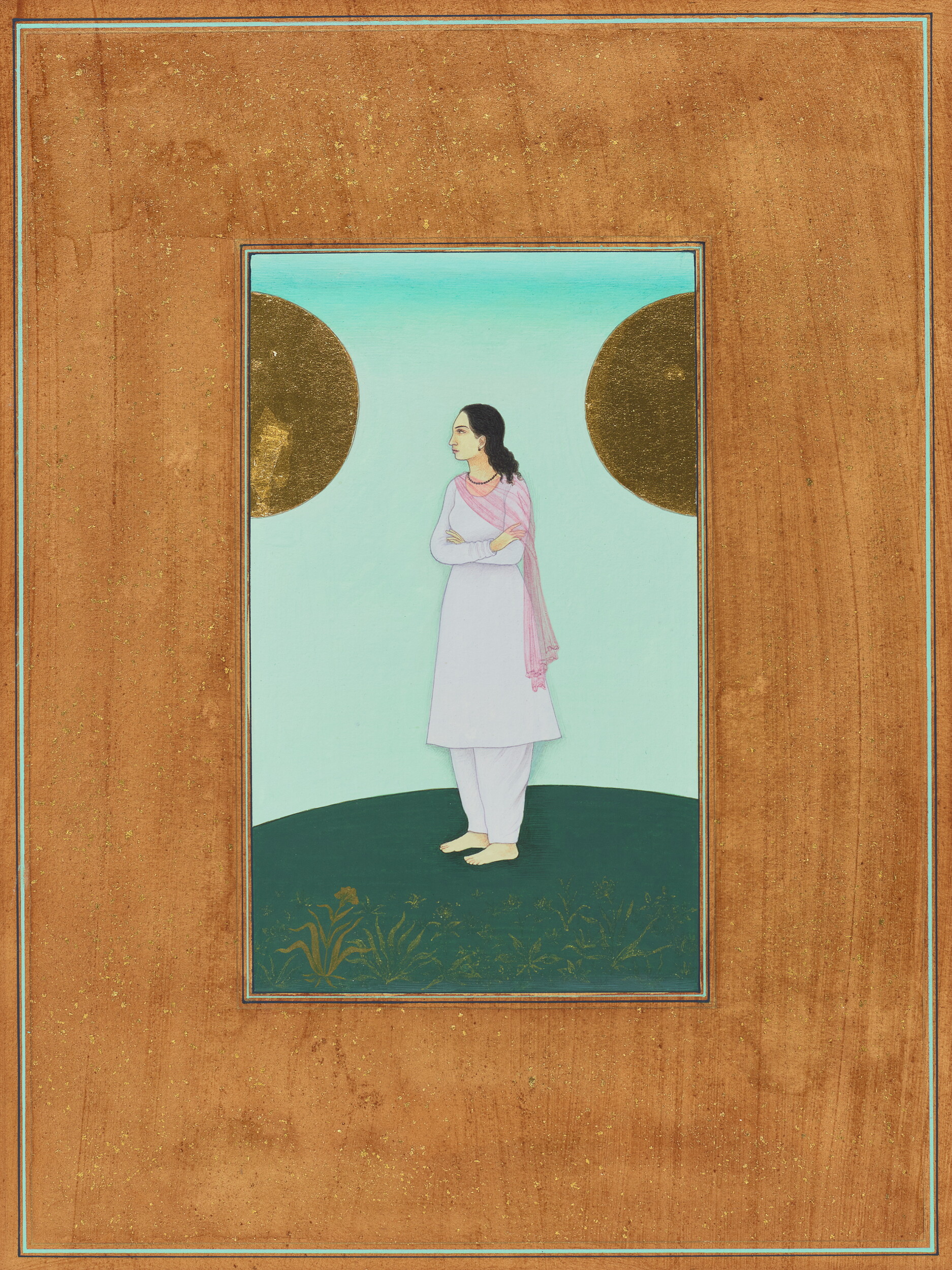

Nusra Latif Qureshi, Descriptions of past II, 2001, gouache, tea wash and gold leaf on wasli paper, 30 x 22 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Bulgari Art Award 2019 © Nusra Latif Qureshi

Pan-historical exhibitions like this can risk misrepresenting contemporary musaviri art as a mere revival of tradition. Qureshi, however, is successful in maintaining a distinct and highly personal perspective on musaviri’s legacies of imperialism and patriarchal power. Rather than adopting the sanctifying mode of the Mughal court, which utilises Persianate visual tradition to reconstruct cultural dynasties, Qureshi’s quietly disruptive paintings erode glorifying narratives. Descriptions of Past II (2001) shows a female subject stranded between two gold halos. Typically framing a court portrait, the halo is a sign of sanctified nobility. In Qureshi’s work, however, the woman is instead caught between two worlds, her arms emphatically crossed as she assesses her next move. As in her earlier student pieces—we see her 1994-5 chronicle of Pakistani history—Qureshi maintains a conventional use of gouache, marginal framing and gold-flecked wasli paper. Only the subject herself, presented in a more simple, modern dress, deviates from a traditional mode of representation. The description suggests that this is an autobiographical work, relating to Qureshi’s feelings of estrangement after moving to Melbourne in 2001 to complete her postgraduate studies.

Qureshi’s disruptions of stylistic convention become more pronounced in her subsequent works as she incorporates acrylic paint and moves away from the page as the compositional framework. A very different portrait figure is becoming eclipsed by a setting orb in …Where The Sun Never Sets (2008) —a work which refers to the 2001 Tampa affair. Qureshi here interrogates the paradox of the surf life-saver as an everyday Australian hero, while national policies dictate routinely turning away asylum seekers at sea. The lifeguards in this work occupy the traditional position of the Mughal court subject; however, their faceless silhouettes merge with the background illustrations, depersonalised and integrated into the cultural fabric of the nation. Ships meander through the composition between the two portraits in a perpetual middle-passage, while the postures of the lifeguards take on a defensive connotation, guarding the work’s borders.

Installation view of the Nusra Latif Qureshi: Birds in Far Pavilions exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, 9 November 2024 – 15 June 2025, featuring Nusra Latif Qureshi Museum of lost memories 2024, site-specific installation comprising objects from the artist’s personal archive, works from the Art Gallery of New South Wales collection, objects on loan from the Powerhouse Museum, and banners produced by the artist © Nusra Latif Qureshi. Photo © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Felicity Jenkins

Ideas around migration and displacement are explored further in Qureshi’s installation project Museum of Lost Memories (2024). Gathering objects from the AGNSW and Powerhouse collections alongside objects from her own archive, Qureshi exhibits a playful and irreverent approach to collecting and display, confronting the very role of the museum in framing discourses of cultural heritage. Display cabinets house assemblages colour-coded with Dulux paint samples. Toy soldiers invade historic prints and vases are up-ended to reveal their accession data. In this context, displaced objects are re-aestheticised in the tradition of the cabinet of curiosity. Qureshi reclaims the role of collector as she unsettles the entrenched values of museum collection, redefining what these objects mean to her as relics of intersecting national, colonial and family histories.

Throughout the exhibition, Qureshi continues to re-centre pictorial narratives around her own contemporary perspective, fleshing out complex female subjectivities and interrogating sub-continental histories of Partition and colonisation. Layering is a key visual strategy for Qureshi as she brings emblems of the Mughal past into new visual contexts. Her work doesn’t demand attention but rewards curiosity. The relatively sparse hang of miniatures across the exhibition space presents a modest view on entry to each room, but as viewers are drawn in, her works open up and begin to reveal complex, densely layered compositions.

In How did Things get to this Point? (2011) tracings of female portraits are overlaid atop one another, amassing to create a hybrid, multi-limbed creature, paralleling the adjacent silhouette of the Hindu god Ganesh. The modest subjects collectively take on a superhuman quality, exhibiting a quiet ferocity as they become the central figures in Qureshi’s visual world. Crossing Partition lines, she mingles the Pakistani heritage of the Mughals with Indian Hindu imagery, reconstructing their intertwined histories.

In …Where the Sun Never Sets the silhouette is another of Qureshi’s strategies for reworking the traditional forms of musaviri painting. Qureshi exhibits the extreme precision developed through her training in this distinctive stencil-like figuration, allowing the many layers of her works to weave through each other, hovering between presence and absence. This technique is used to visceral emotional effect in her couple portraits. Whereas portraits of lovers conventionally illustrate Sufi poetry and evoke divine ideals of love and beauty, Qureshi’s spectral encounters are estranged by impassable cultural lacunae. Precious Strings of Pearls (2006) shows a tender encounter as a red male silhouette appears to hand an object to the female subject. Withholding visual information, Qureshi imbues the relationship with ambiguity—what is being passed between them? While the woman holds the spectre’s hand, her gaze passes through him, signifying his precarious presence within the narrative space. Peculiarly, seeing historical portraits alongside these works incites us to seek out ghostly presences secretly residing in them as well, and to imagine what stories have been lost to history.

Nusra Latif Qureshi, Portrait settings, 2020, diptych: gouache and synthetic polymer paint on illustration board, 28 × 42 cm overall. Collection of the artist © Nusra Latif Qureshi

Absence and presence also co-reside in Qureshi’s reproductions of historic studio photography. Popularised in the Indian subcontinent by the British in the nineteenth century, photographic portraits developed into a cultural hybrid artistic form as musavir artists began to colour and embellish these photographs. We see several examples in the Museum of Lost Memories, in which sepia-toned subjects are adorned with vivid blue and yellow robes or turbans. Just as we are unsettled by the resemblance between Qureshi and the circus dancer, so too, seeing these historic subjects re-contextualised, we become aware of the unusually manufactured realities suggested by these photographs, which nevertheless correspond to real personal histories.

Qureshi re-presents the photographic colonial gaze in new visual encounters, eroding the implied objectivity of the medium. In Accomplished Missions I, II and III (2012), photographic traces are dwarfed by giant hands, frozen in eloquent gestures. Hands play a particularly expressive role in Qureshi’s compositions, evoking the spiritual tempers of Hindu mudra. Their open palms and active gestures contrast the stoic Victorian postures, activating the stifled energy of the portraits.

In her constructed encounters, images both reveal and conceal one other. These traces alternately layer upon each other into obscurity or combine to form poetic collages, and at other times dissolve into ambiguous vestiges of form, as in Marginal Thoughts I and II (2008) In this sense, Qureshi’s practice embodies the flow and ebb of cultural memory through the perpetual transition of forms.

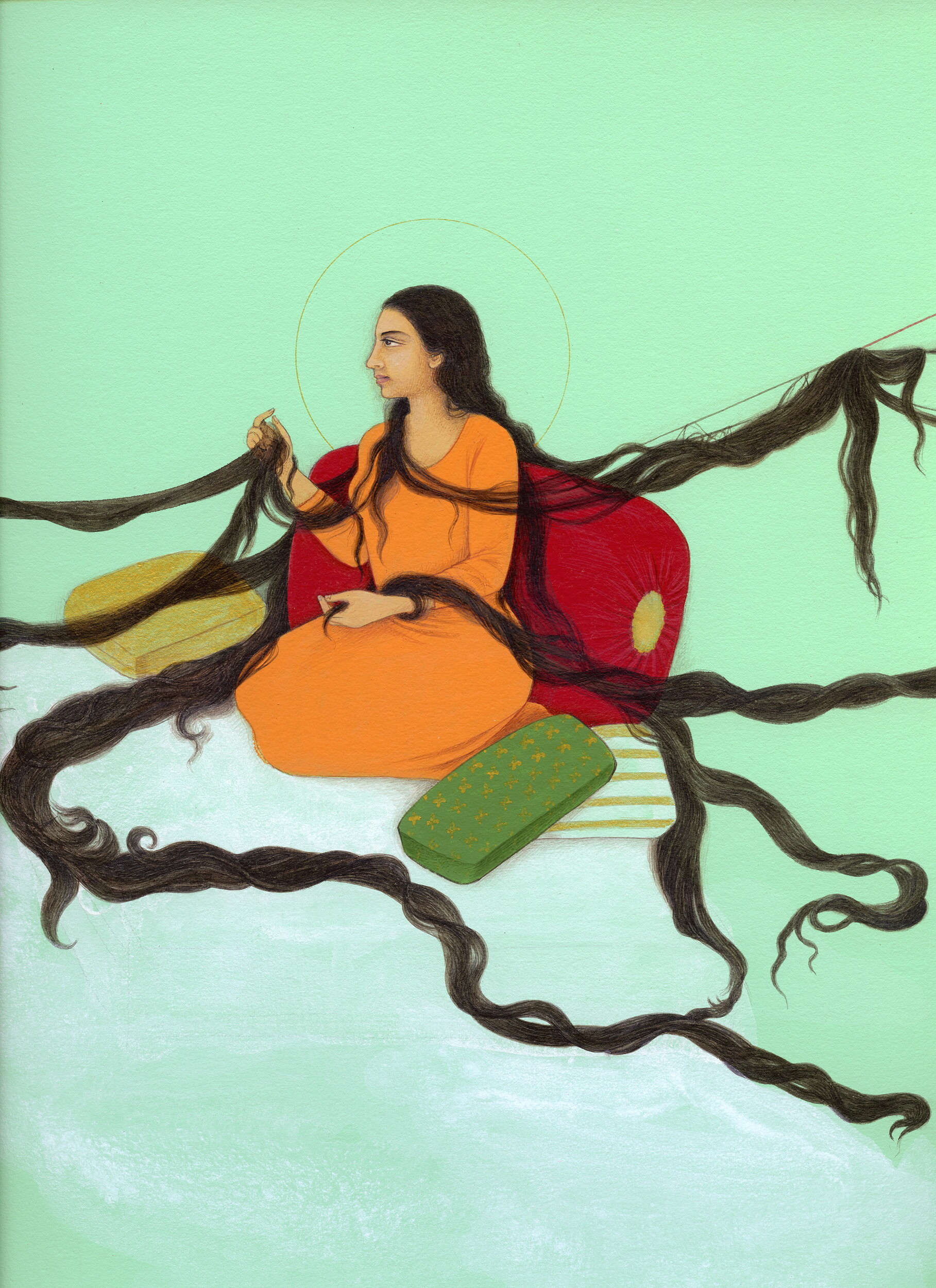

In Medusa’s Respite Room (2017), Qureshi is sat amidst these flowing strands of history and tradition. The hair of Medusa is alive and unwieldy, but ultimately comes from her own body. We see her taking hold of this tangled web, beginning to unravel it strand by strand. Is Qureshi deconstructing historical art practices and building her own visual language from these threads? To see Qureshi’s work is to understand that history isn’t something to find or rediscover from the past, but is always woven through our encounters with the present.

Nusra Latif Qureshi, Medusa’s respite room, 2017, gouache and synthetic polymer paint on illustration board, 32.5 × 25 cm, The State Art Collection, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, purchased 2018 © Nusra Latif Qureshi

Amelia Langley is a writer from Eora.