Carlton’s Public Housing towers and surrounding landscape. Photograph by Veronica Charmont.

Carlton Public Housing Estate

Yowhans Kidane

On Tuesday, 19 September 2023, the Victorian government announced plans to demolish Melbourne’s forty-four public housing towers, sparking widespread outcry from architects, academics, lawyers, public housing residents, and politicians across the political spectrum. This growing frustration was highlighted at a talk titled Care and Repair: In Existing Infrastructures, Communities, and Country, held on 27 May 2024 as part of Melbourne Design Week. While the panellists approached the issue from different perspectives, they broadly advocated for a “reparative” and “care and repair” approach, one that sought not only to preserve the towers but also the communities and social networks within them. Since then, these ideas have been reflected in proposals advocating for the retention and refurbishment of certain public housing towers, with similar sentiments echoed by prominent Melbourne architects in the media.

It is hard to dispute the merits of refurbishing the towers, whether in terms of environmental benefits, minimising disruption for residents, or preserving the communities within them. However, among the many arguments for preserving Melbourne’s public housing towers, their historical value, both architecturally and socially, emerges as particularly significant. As the Care and Repair discussion unfolded, through insights from both the panellists and the audience, what struck me most, especially as a former resident, was the dramatic shift in public attitudes toward the towers. Once stigmatised for their aesthetic and spatial qualities and, perhaps not unrelatedly, the types of people they housed, the towers now appear to be seen, at least by some Melburnians, in an entirely new light. This shift raises key questions: How and why has public sentiment toward the towers changed so dramatically? What accounts for this newfound appreciation? And, most importantly, what is truly being preserved in the calls to save them?

To address these questions, it is essential to first understand what preceded the Carlton public housing estate and the context in which the towers emerged. While this history has been explored elsewhere, it is worth revisiting briefly, as the growing opposition to slum reclamation, along with its underlying causes and modes of expression, came to shape, and continues to shape, the suburb of Carlton and the estate’s place within it. The site now occupied by the Carlton public housing towers was once designated a slum area. It consisted of a patchwork of named and unnamed streets, cul-de-sacs, and lanes, many of which have since disappeared. In the early 1960s, the dwellings on this site were gradually demolished as part of a broader slum abolition drive, paving the way for the four high-rise towers that dominate the site today, along with several walk-up flats that are no longer extant.

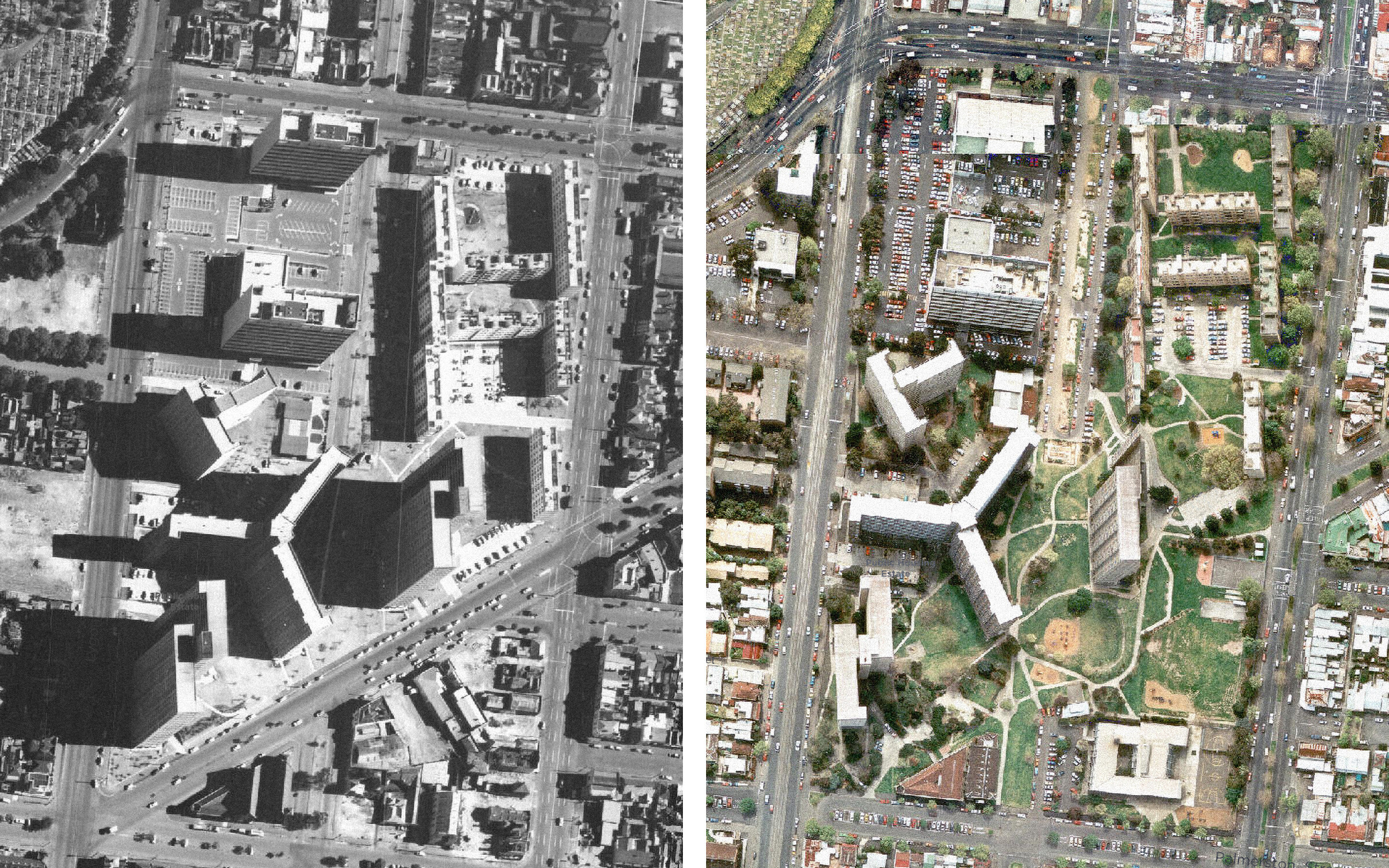

Left: The newly built estate, 1967. Right: The estate, 1994. Note the walk-up flats in the top right have since been demolished and replaced with social-mix housing.

The largest and most populous tower on the Carlton housing estate is located at 510 Lygon Street, also known as the Y-shaped building. To understand why it was developed this way, as opposed to the two S-shaped and one T-shaped buildings on the site, it is important to recognise that the Carlton housing estate did not emerge as a monolith. Instead, it should be viewed as a composite of several demolished slum areas, each razed and redeveloped at different times. The Y-shaped design, then, seems to have been an attempt to efficiently utilise the space on the High Street site of the emerging estate. Although these building types have since gained appreciation for their expression of high modernism, the reception of these towers soon after their construction was rather different.

Post-war, Carlton was a suburb undergoing significant change. By the 1950s and 60s, working-class tenants were being gradually replaced by “New Australians” and members of the gentrifying middle class, particularly staff and students from the University of Melbourne. These newcomers began restoring and upgrading the suburb’s cottages and terraces.

When the Housing Commission of Victoria sought to reclaim the block bounded by Lygon, Lee, Drummond, and Princes Streets, a group called the Carlton Association was formed. Led by “a small circle of academic activists”, the association’s opposition to plans to build public housing in this area operated on two levels. First, it was a defensive response from private residents to a planning logic that threatened their homes and property values. This narrower concern is evident in one of their publications, which states:

They (private residents) consider that the terraced house offers more opportunity for their style of living and for capital appreciation than purchasing a flat. It seems obvious that if they are in a position to continue to purchase terraced houses and improve them, the standard of the locality would be considerably upgraded and in the course of the next few years would become comparable to Parkville or East Melbourne.

The Carlton Association’s activism was thus driven by a desire to raise the socio-economic status of the area, an outcome from which they, as owner-occupiers ready to renovate, stood to benefit. This aspiration to improve the area was closely tied to a growing appreciation for the historical architectural character of inner-suburban Melbourne.

A view from inside one of the freshly built towers shows how Neil Street looked in the 1960s. Today this area is pedestrianised. Photograph by Alan K. Jordan, courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

The group’s activism reflected a broader cultural shift in attitudes toward Australian architecture and housing, one that underpinned the emerging valorisation of suburbs like Carlton, parts of which had previously been considered slum areas. Although now considered “iconic,” many of Carlton’s cottages and terrace houses were once seen as outdated and undesirable. In the early twentieth century, deeper setbacks and larger gardens became the preferred features, leaving these types of smaller homes predominantly occupied by working-class communities. Carlton’s changing social composition precipitated a reassessment of the value of these once-stigmatised houses.

The works of neurologist and conservationist E. Graeme Robertson and architect David Saunders played a key role in cultivating interest and appreciation for the older buildings of Carlton and their distinctive features. The Carlton Association, deeply influenced by these works, integrated their ideas and arguments into its activism and publications, which circulated shortly after the construction of Carlton’s public housing estate. This influence is especially evident in the association’s report, Housing Survival in Carlton: Objections to the Housing Commission’s Proposal to Reclaim the Block Bounded by Lygon, Lee, Drummond, and Princes Streets. The report argued for preserving Carlton’s character by framing its cottages and terrace houses as “uniquely Australian” and of “architectural and historic interest,” qualities that contribute to the “character of Melbourne.” The group critiqued modernist planning and bureaucratic overreach, ironically, themes that contemporary advocates of high-rise development now seem eager to revive. It warned against the erasure of local distinctiveness, stating: “Carlton has unique people, unique buildings, unique character, but it is getting so that there will be no sky left, no space left, no style left, no say left.” The report also rejected high-rise flats as appropriate homes for families, contending that such buildings “do not cater for family life.” These arguments collectively formed a defence of Carlton’s architectural, social, and cultural identity, which was under threat from a state redevelopment agenda prioritising uniformity, efficiency, and density over community, heritage, and liveability. These arguments may sound familiar. Today, similar rhetoric is used to support the retention of the towers, particularly the idea that their heritage or iconic status is integral to Carlton’s “unique character.”

In the long arc of Carlton’s history, the place of the Carlton Association is an ambivalent one. What attracted many members of the group to the suburb was not only its architecture and housing but also its vibrant character and diverse social composition. However, the arguments and concepts the group employed to preserve Carlton set in motion forces and dynamics that, over time, irreversibly altered the character of the suburb. This shift often conflicted with the preferences of some members, who continued to live in Carlton and lamented the loss of the qualities that had originally attracted them to the area.

While the liberal sensibilities of the incoming, gentrifying middle class may have made open hostility toward the estates difficult to express, it is unlikely that those focused on capital appreciation viewed the estates with much enthusiasm. The stark towers of the estate, with their increasingly diverse and often working-class tenants, contrasted sharply with the suburb’s evolving image and aspirations. Indeed, although the Carlton Association and its members were not necessarily opposed to low socio-economic groups, the fact that the aesthetically incongruent towers and their tenants were seldom discussed or focused on in the group’s activities suggests they existed outside the conceptual boundaries of the Carlton they envisioned; it was simply “over there.” It is not far-fetched to suggest that, over time, many of Carlton’s increasingly affluent private residents saw the towers as an unfortunate imposition, an aberration to be silently endured.

An oblique aerial view of Carlton captures how the public housing towers challenged the pre-existing streetscapes. Date unknown, presumably 1960s. Photograph by Colin Sach, courtesy of the University of Melbourne Archives.

Nowhere is the estrangement between the towers and their surroundings more evident than in the social and physical disconnection of the estate from the rest of Carlton. Prior to its refurbishment between 2005 and 2017 (a point we will revisit), the estate existed as an isolated ecosystem, physically separated from the wider suburb. The now-demolished public walk-up flats once lined Rathdowne Street, casting a long shadow as if marking a boundary and signalling the start of a different zone within Carlton.

The estate’s internal layout further reinforced this separation. Its pathway system seemed designed more to facilitate internal foot traffic than to encourage connections with the surrounding streets. Although memory can be an unreliable ally, I seldom recall outsiders venturing into the estate or using it as a thoroughfare when I lived in the area during the 1990s and early 2000s. A patron of the Carlton Baths, disembarking from the number 1 tram, might well have chosen the longer route via Princes or Elgin Street, rather than cutting through the towers.

The estate’s design and its separation from the wider suburb were, of course, determined by the Housing Commission of Victoria, likely without the intention of creating such a divide. However, over the decades, the persistent reluctance of many Carlton residents to engage with the estate and its tenants only reinforced this divide. What began as a planning decision gradually evolved into a lived social reality, ultimately marking the towers as out of step with the suburb’s shifting socio-economic and architectural identity.

This ingrained sense of separation did not, however, remain static. In the 2010s, it was reframed through state-led redevelopment, under the guise of “social mix” – the idea that the rich can uplift the poor simply by being in close proximity to them. As part of a broader refurbishment, the old walk-up flats, archaic for various reasons, not least their lack of accessibility, were demolished, and much of the land they occupied was sold to private developers. On the razed sites, the cubes we now see facing Carlton Baths were constructed. The so-called increased “engagement” with the public housing estate, however, did not signal a rejection of gentrification or an embrace of the towers. Instead, it facilitated the integration of “gentrifiers” into the estate, with both public and private dwellings now coexisting on-site. This approach has since become common in social housing projects.

The Carlton Public Housing Estate has been opened up to the rest of the suburb, with the inclusion of a futsal court at the base of the towers. Photograph by Veronica Charmont.

In practice, then, “social mix” appears to have served as a legitimising discourse for changes that effectively amounted to the encroachment of the estate by the wider suburb. Under its cover, the estate was fundamentally reshaped, both physically and socially, largely to the detriment of its inhabitants. The internal landscape was reconfigured: the terrain was levelled to make it more inviting to outsiders; the previously neglected basketball court was refurbished; a sleek futsal pitch was introduced (initially accessible by booking, including to non-estate residents); and a skate area was installed, despite residents rarely being seen with skateboards. Pathways were reoriented to facilitate movement through the estate, particularly for cyclists and passers-by, rather than circulation within it. These interventions served less to enhance the lives of existing tenants than to make the space more permeable and legible to those from outside.

The result was a near-total hollowing out of the estate’s public social life. Walk through it today, at almost any time, and you are just as likely to encounter an outsider as a local, a stark departure from the past. As someone who knew the space before the refurbishment (albeit hazily) and who continues to move through it today, I had long suspected this shift. That sense was confirmed by Idil Ali, who lived through the transition and spoke of how the redevelopment had drained the estate of its once-vibrant social life. Strikingly, and in contrast to the outcry we see today, these relatively recent transformations provoked little public opposition from Carlton’s private residents. Perhaps the language of “social mix” and its supposed benefits of communal integration were enough to assuage any misgivings well-intentioned Carltonians may have had. It is also tempting to think that some quietly welcomed the erasure of features they saw as blights, detrimental to the capital appreciation of their homes.

A pathway network enables Drummond Street to continue through the centre of the public housing towers. Photograph by Veronica Charmont.

My argument here may seem contradictory: frustration with the estate’s lack of integration into Carlton alongside dissatisfaction with its eventual “integration.” The issue, however, is not integration per se, but how it was carried out. Ali’s memoriesreveal a preference for the estate to remain an isolated enclave, a desire shaped by the surrounding community’s rejection of its residents. Given this context, how could one embrace an integration, especially one as disingenuous as that carried out under the guise of a social mix, that not only reinforces this dynamic but also undermines the estate’s status as a refuge?

It is clear, then, that for much of the towers’ existence, little has changed in how they have been perceived by the private residents surrounding them. Their long-standing indifference, or at times, muted hostility, arguably laid the political groundwork for the towers’ proposed demolition. So, how do we explain this sudden shift, where some, particularly from a demographic that once detested the towers, now seek to preserve them?

The answer may not be as far removed from the detachment underlying the above sentiments as one might think. This is particularly evident in the heritage arguments put forward in favour of preserving the towers. Christopher Lee, a former tower resident turned architect who nominated the Park Towers in South Melbourne for heritage status, argued for their preservation by stating that they were “one of the purest examples of (French architect) Le Corbusier’s principles from that period in Australia.” Urban historian David Nicholls offers a different perspective: “It seems to me very short-sighted to pull them down; demolishing them would be like erasing an element of Melbourne’s working-class history.”

What emerges from both examples is that the motivations for preserving the towers reflect, at least in part, an effort to honour them as monuments to a specific architectural or social past. On a deeper level, and perhaps implicit in Lee’s invocation of Le Corbusier, the towers are increasingly being reimagined through the lens of contemporary social and political anxieties, particularly those surrounding housing, which are (paradoxically) being resolved through a projection onto a romanticised past. As one article noted, “Long seen by many as a blight on Melbourne’s landscape, the towers are now being more sympathetically viewed amid a housing crisis, as attitudes to high-density living shift.” From this perspective, the impulse to preserve these modernist monoliths may reflect a nostalgic longing to revive the social ethos that originally underpinned their construction, at a time when belief in collective progress has largely waned.

Another way of interpreting the outcry against the towers’ demolition is to see it not as a break with the past, but as the final expression of inner-suburban gentrification. It represents a resolution of long-standing ambivalence toward public housing in areas like Carlton, not by bridging the historical divide, but by recasting the towers as cultural artefacts, symbols of a social ethos that has long since faded. In a somewhat twisted irony, history has come full circle: the aestheticisation that began with Carlton’s terrace houses has now breached the last, once-insurmountable frontier: the towers themselves. Whether this will eventually lead to the “trendies” infiltrating its halls, particularly if refurbishment occurs, remains to be seen.

Yowhans Kidane is an archivist currently working at the University of Melbourne Archives in Naarm/Melbourne.