Grace Crowley, Composition - movement, 1951, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1993 © The Estate of Grace Crowley

Cézanne to Giacometti: highlights from Museum Berggruen / Neue Nationalgalerie

Katrina Grant

The images I can’t stop thinking about from the NGA’s current exhibition are Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s detention-centre prints. The three prints show clusters of figures looking out through barbed-wire fences. In one, a pair of seated figures sit on the ground, dark silhouettes against a dark night. A barely visible web of wires separates them from a brightly lit space, with a second fence, a small figure (a guard?), and a watchtower. Beyond them is a dark, inky sky filled with stars. What are they looking out at? The stars or the fence?

Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack, Australian Night Sky. Hay, 1940-1, drawing in watercolour, black ink over pencil, additions in varnish, 19.7 x 28.7cm. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra.

In 1936 Hirschfeld-Mack fled Nazi Germany, only to be detained in the UK as an enemy alien. He was one of thousands who were shipped off on the Dunera to Australia when UK camps became overcrowded and who spent the rest of the Second World War in various internment camps in regional NSW and Victoria. Hirschfeld-Mack’s prints are displayed in a room dedicated to the “Bauhaus in Australia”, along with sculptures by Inge King and Clement Meadmore, linking the politics and art of early twentieth-century Europe with Australia.

These darker moments of isolation, dislocation, and harm caused by the politics and conflicts of the twentieth century are a background note to the NGA’s 2025 winter blockbuster. The core of the exhibition comprises paintings, sculptures, and drawings from the Berggruen Collection, a museum under the custodianship of the National Gallery of Berlin. The museum is currently shut for renovations, so the collection is travelling.

The works were originally amassed by the German art dealer Heinz Berggruen. In a video at the entrance, it is Berggruen himself (who died in 2007) who introduces us to the history of his collection and museum. The themes of upheaval and conflict are raised again. Berggruen was forced to flee Nazi Germany, like Hirschfeld-Mack, in 1936, and lived most of his life in the US and France having, in his words, “turned my back on my homeland.” The video frames the collection’s return to Berlin as a “gesture of reconciliation.” The exhibition is, ultimately, not really about politics, nor focused on themes of forced migration and the arts. Yet these are a quiet thread through the exhibition. Maybe one that deserved to be a bit louder given current politics. We have seen a rise in crackdowns on artists whose work criticises the rise of fascist politics and autocracies, both in Australia and overseas. There are daily images of conflict and dislocation from wars around the world. In the days leading up to my visit to the exhibition I had been watching the debates about planned mass protests against the war in Gaza, and this exhibition triggered reflections about how these wars are connected to the ongoing legacies of the conflicts of the twentieth century.

Instead, the exhibition pulls our attention in several other directions. The Berggruen Collection is based on the classics of twentieth-century modern art, focused on the artists, mostly from Europe (and particularly France), who pushed art in new directions from around 1900 up to the middle of the century. The loans from Berlin form a core of modern “masters,” and the exhibition walks us through a bit of a lesson in Modern Art 101. The exhibition opens with a room focused on Paul Cézanne; he is framed as the great experimenter who helped European art “break free” from linear perspective. This follows the standard opinion put forward by Clement Greenberg that modernism was defined by the flattening of the picture plane, which led finally to Abstract Expressionism.

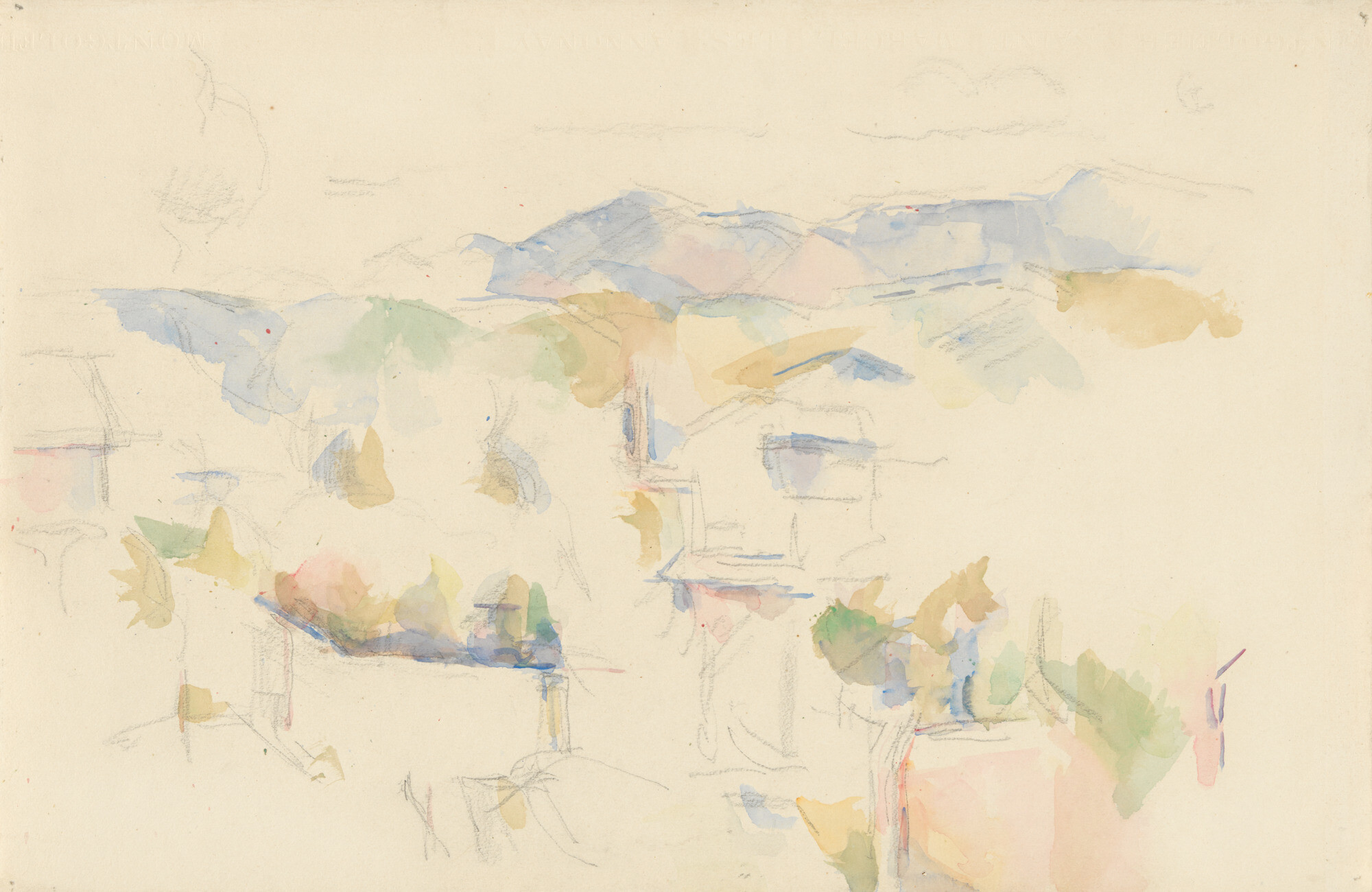

The idea of perspective as a sort of aesthetic prison for art that had to be broken out of is returned to several times in the exhibition, yet in many ways the paintings and drawings across the first rooms are shaped by a preoccupation with perspective and pictorial construction. But while the traditional (Renaissance) technique of linear perspective sought to create an illusion of real three-dimensional space, Cézanne and the artists who followed him sought instead to dissect the space, they cluster shapes together as fields of colour or cut them apart with intersecting lines. A watercolour by Cézanne at the start of the exhibition shows these effects: colour is used to create form, and depth is created not by a recession of forms to a vanishing point but through layers with the shapes of mountains stacked together. Yet the composition can also be read as directly responding to existing modes of constructing landscape views in art. For centuries artists had used layering of forms, often in horizontal bands of foreground, middle ground, and background, to create depth as much as single-point perspective (you can see these techniques elsewhere in the gallery). Cézanne’s innovation here is perhaps more about the abstraction of these forms to rough shapes and colours.

Paul Cézanne, Paysage montagneux, environs d’Aix, c. 1895. Watercolour, pencil on paper, 31.4 x 47.6cm. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra

The significance of cubist George Braque is framed in similar terms. His 1907 painting Houses at L’Estaque is introduced with a quote about saying “goodbye to the vanishing point.” The street at the bottom of the picture begins to recede as one might expect in a more traditional landscape painting, but the houses don’t gradually recede to a distant point. Instead, they are layered one on top of the other, pushed up close to the picture plane. Walls, streets, and landscape are reduced to angular shapes in the same pale orangey cream, outlined in blue.

Braque, of course, took the concept of layered forms a step further in his later paintings, such as the 1913 Still Life with Glass and Newspaper. Fragments of newspaper and glass are layered in a jumble; there is no depth here, everything is pushed to the surface of the picture plane. Instead of manipulating the way our eyes judge depth to create an illusion of space, as linear perspective can be used, here Braque alludes to the fragmented way we see the world, in glimpses and with a fractured focus. The room dedicated to Paul Klee shows more of these experiments in seeing the world differently through art. His studies of colour and form bring everything together on the flat picture plane: architecture, landscape, figures, and abstract shapes are all elements for exploring the rhythm of lines and colour. It would be easy to read Klee’s coloured abstractions of the built and natural world, or his line drawings where he follows (quite deliberately) a child-like way of depicting the world, as esoteric reflections on the nature of colour or even whimsical observations. Yet again I found myself wondering about the impact of the political turmoil of the period. In one wall label we are told that “political hostility resulted in the closure of the Bauhaus,” a rather tame statement that belies the constant hostility towards the art and artists connected with this institution, which eventually saw many of them (like Hirschfeld-Mack) flee Germany. In this context, Klee’s embrace of a childlike view of the world could be read not only as a rejection of academic tradition but as a rejection of an establishment, or politically conservative, view of how we should see and depict the world.

Cézanne to Giacometti: highlights from Museum Berggruen / Neue Nationalgalerie, installation view, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, 2025

Following Klee is a room dedicated to Picasso portraits (with photographs by Dora Marr—a nod, presumably, to the NGA’s ongoing Know My Name initiative to highlight women artists traditionally marginalised from art history), then Matisse with a mix of paintings, sculpture, costume, sketches, and cut-outs. A final room ends the lesson in modern masters with Alberto Giacometti and a return to the idea of rejecting perspective, this time with sculptural forms. It’s a good walk through the history of modern art, but it’s not the whole story.

Alberto Giacometti, Tall nude standing III (Grande femme debout III), 1960 (cast 1981) and Slim woman without arms (Femme mince sans bras) 1959‒60, installation view, Cézanne to Giacometti: highlights from Museum Berggruen / Neue Nationalgalerie, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, 2025

Alongside the masters from the Berggruen Collection, the exhibition tells a second story with a range of works drawn from the NGA collection. It is not uncommon for galleries to slip works from the permanent collection into a travelling show, but often this is done to give context to individual works in the permanent collection that obviously fit with the visiting collection. Instead, in Cezanne to Giacometti the integration of NGA works has a more pointedly national character. The curators have set Australian artists like Grace Cossington Smith, Dorrit Black, Roland Wakelin, and Inga King in conversation with the European masters.

Grace Cossington Smith, Recto (A): Skillion; Verso (B): Not titled (Landscape), c 1931, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1976 © Estate of Grace Cossington Smith

We see how Grace Cossington Smith (1892–1984) developed Cézanne’s and Braque’s landscapes of stacked forms into a Landscape (1931), created by a series of abstract curves and angles, where she uses colours and sparse outlines to help us distinguish trees from rocky bluffs, a river, and a distant mountain. Another Cossington Smith painting of a Sea Wave (1931), rendered in contrasting bright squares of thick paint, makes an excellent counter to Klee’s Classic Coast (1931), in which he reframes the techniques of post-impressionists like Seurat. Klee’s version of pointillism creates an image that is difficult to resolve into a coherent view; we can pick out the line of white waves breaking, but mostly you have to focus and then refocus across the picture. It would have been great to have hung these two paintings side by side, but mostly there is a bit of a physical separation between the visiting art and the NGA collection, hung in different clusters or on different sides of the rooms. The broader point nonetheless seems to be that these Australian works, made at similar times on opposite sides of the world, show how modern art was not just a European phenomenon.

In this way the exhibition introduces its public to the debates and explorations of what is meant by “Australian art” that have been part of art history since the late twentieth century but seem to be filtering into exhibitions in a more obvious way in the last decade or so. Recent research and writing by Rex Butler and ADS Donaldson, amongst others, have introduced the idea that definitions of Australian art should be more complex—or simply avoided altogether. Art historians and artists now argue that it is often difficult (even counterproductive) to enlist an artist to a single nationality or national project. At the same time, these discussions raise questions about the role of place in the making of art, and of art in the making of place. Do certain paintings and sculptures look Australian? How much do local artists shape how we see the world around us? In recent years the NGA has been making some subtle changes to reflect this, such as adding to the art labels the various places around the world that artists have lived and worked in, rather than tying them to one nation, revealing many formerly “Australian” artists to be migrants, emigrants, and generally peripatetic subjects with an eye on the wider world.

Australians in the early twentieth century were, to be sure, deeply interested in what was happening in Europe. And the lines of influence did not only flow in one direction. The Impressionist painter John Russell, born in Australia but mostly resident in France, is introduced in the room on Matisse. Visually, Russell’s 1891 Impressionist landscape sits a bit unexpectedly alongside modern works from the 1920s–40s, but his presence is deliberate. Matisse, as Rex Butler and ADS Donaldson have explained, believed that he owed a debt to Russell for helping him to discover new ways to work with colour. The exchange of ideas between Australia and France continued into the twentieth century, as shown in Grace Crowley’s stencil and gouache Composition-Movement (1951). She had spent time in France with closer friend and fellow Australian artist Anne Dangar and, from the 1930s, played a key role as a teacher in the dissemination of modernist French art in Australia.

Cézanne to Giacometti: highlights from Museum Berggruen / Neue Nationalgalerie, installation view, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, 2025 (with view of Georges Braque Houses at L’Estaque 1907).

It’s a much bolder integration of permanent collection with loans than we usually see for temporary exhibitions, and it is mostly a good thing. At times, it does feel like there are two exhibitions happening alongside each other, one (a powerful one) about European modern art, and one (much less interesting) about how Australian artists were inspired by it. But I was looking for some bolder statements too about the politics and history. To circle back to where I started, there was an opportunity to draw out themes about the rise of fascism and its impact on artists. It forced artists to move, to relocate, or to stay put. The Australian artist Anne Dangar remained in France and died shortly after the war, an early death caused by malnutrition and the stresses visited on the civilian population (as explored in the NGA 2024–25 summer exhibition on Dangar). Could this have been tied more strongly to the argument revisited several times about artists escaping the tyranny of conservative artistic practice? How did the violent upheaval and political turmoil in Europe push artists to look for new ways to document the world around them? What role did this play in the dramatic changes in visual culture that rippled around the world? While I acknowledge the constraints of a large loan exhibition, the idea to put the Europeans in their place and ask them to converse with the locals is interesting, but we can surely extend this also to be a conversation with the present day. The prints by Hirschfeld-Mack of Australia’s Second World War detention centres were powerful to me not only because they documented the terrible impacts of a historic conflict, but because they are all too familiar as ongoing traumas we see every day in the news.

Katrina Grant is a writer and art historian who lives in Canberra on Ngunnawal and Ngambri land. She is currently a Research Fellow in Visual Understanding at the Power Institute for Arts and Visual Culture, and current President of the AAANZ.