Installation view of A Modern Turn, Castlemaine Art Museum. Photo: James McArdle.

A Modern Turn

Amelia Winata

It’s cursed Leo season again. That’s what I think as I enter the first gallery at Castlemaine Art Museum. I’m here to see A Modern Turn, but to get to that show one must first pass through Framed, an exhibition that “looks at the intimate relationship of a work of art to its frame.” The exhibition runs for exactly one year, and I can’t help but think that the recent departure of the museum’s director Naomi Cass might have something to do with the exhibition overstaying its welcome. To be fair, there are some great works in the show. A tiny Clarice Beckett, Wet Evening (c. 1927), that depicts a car driving along a wet road, the moon reflected onto its surface, is part of the museum’s collection. It’s beautiful. From the didactic I learn that the simple turned-wood frame was made by John Thallon, a framer Beckett used throughout her career. A display case of mouldings and compo on loan from the NGV’s conservation department makes me less excited.

Onwards and upwards. A Modern Turn is a group exhibition that, according to the museum, “focuses on the post-WW2 period when a gentle modernism was embraced by many Australian artists and seeped into the work of even the most conservative of artists.” A quick Google suggests that “gentle modernism” is more often associated with architecture and design—I saw it assigned to Alvar Aalto—and involves a melange of modernist formal elements with perhaps less attention given to the theoretical underpinnings of modernism. For the Castlemaine exhibition, however, this term seems to operate as a catchall for art produced with any reference to modernist styles (and let’s be clear, these are European modernist styles). For the most part, the exhibition is also a collection show.

The pedagogical influence of George Bell and, to a lesser degree, Arnold Shore, is emphasised throughout the exhibition. From 1922 Bell taught painting at his Toorak home. In the early 1930s, Shore and Bell opened a painting school in Melbourne but parted ways only a few years later. Indeed, a vast number of works by Bell and Shore are on display and represent the hyper-localism of their practices. Shore’s Darling Street, South Yarra (1936) was painted close to his Windsor home and is a typical example of modernist formal experimentation, employing broken colour to represent the South Yarra residential streetscape from above. Several of Bell and Shore’s students are featured in the exhibition, including Peter Purves Smith, Yvonne Atkinson, Guelda Pike, Cybil Craig, and Ian Armstrong. Also present are artists who worked in their orbit, such as Danila Vassilieff, William Frater, and Albert Tucker.

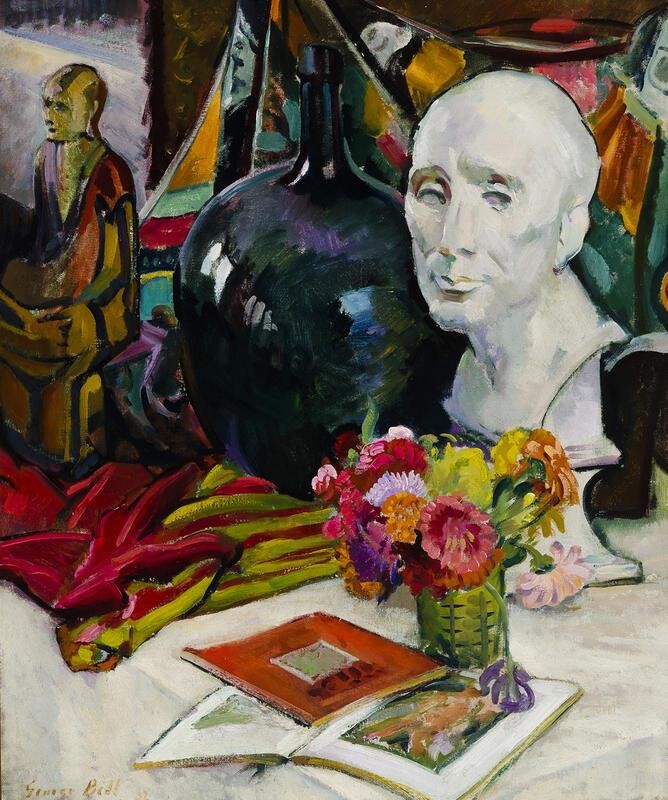

George Bell, Still Life No. 13 (Studio) (1932). Oil on canvas, 76.7 x 63.7 cm. Courtesy of Castlemaine Art Museum.

There are two dominant lenses through which art historians (unofficially) assess the worth of art. The first is through innovation and aesthetic value, while the second is through the lens of “how did this contribute to art history?” (aka: “this is mid, but we had to go here before we got to there.”) The legacy component of A Modern Turn might just be part of category B. Indeed, for the most part, Bell’s innovation was a wholesale transplant of various European modernist styles to Australia, which he then modified, often combining formal elements as pastiche. Bell’s Still Life No 13 (studio) (1932), painted prior to what is said to have been Bell’s 1935 watershed-moment trip to Europe, nonetheless shows him moving towards modernist fragmentation and a decidedly Cézanne-esque sloping plane. While the 1935 trip is said to have exposed him to Cézanne, it appears he might have been familiar with his work already. Showcased as it is in the exhibition, the organisers seem to want to highlight this as a dawning of a new age. Which it was for Bell, at least. His previous works were unequivocally realist, modelled on Raphael and, eventually, Max Meldrum’s tonalism.

A great deal of attention is paid to Dorothy Braund and Yvonne Atkinson as key disciples of Bell. Atkinson, whose work I was not familiar with previously, was a pleasant surprise. The three displayed works clearly demonstrate her progression from the style clearly learnt from Bell towards Atkinson’s own defined aesthetic. Specifically, we have The Tram Stop (1937), painted as Bell’s student, and then Undertakers’ Picnic (1964), which might have been modelled on Matisse (a group of suited caretakers arranged in a circle of alcohol-induced ecstasy is a reminder of Matisse’s Dance), but has a caricatural quality to it. It’s a shame the gallery could not borrow the painting The George Bell Art Studio (1937) from the NGA, which not only explicitly makes the link to Bell but is a great painting that combines German expressionist formal qualities with Bell’s sloping perspective and planar colour blocking.

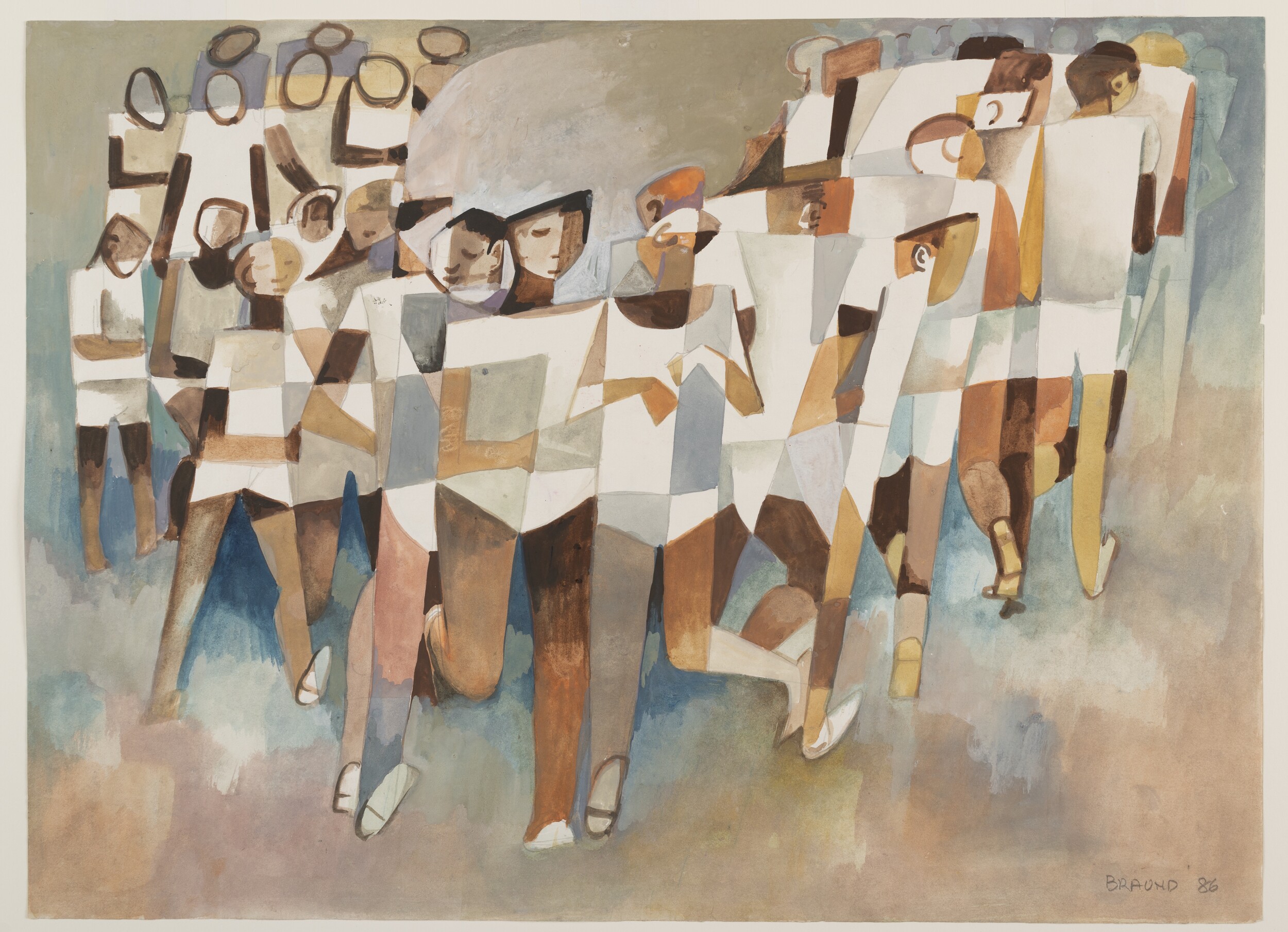

Dorothy Braund, Fun Run, 1986, gouache on paper, Castlemaine Art Museum. Gift of the artist, 2010.

Yvonne Atkinson, The Tram Stop, 1937, Oil on cardboard mounted on composition board, Castlemaine Art Museum. Gift of the Artist, 1977.

Braund’s work, on the other hand, overwhelms A Modern Turn. I counted thirteen works by the artist, most of which were made in the 1980s—a liberal interpretation of “post-war.” The paintings, which are mostly illustrative representations of the human form repeated over and over, are nothing to write home about, and they dominate nearly an entire wall of the gallery, real estate that was sorely needed in this cramped hang. The general sense is that this wholesale dump of Braund and Atkinson’s work is the organisers’ attempt to present a revisionist history of Australian modernism. The dudes taught, but the women were the real heroes. It also deflects from the Margaret Preston work titled Aborigines Preparing for a Fight (c. 1954). The display of this work, which depicts a throng of bodies—said “Aborigines”—wielding spears and a couple of shields—only stokes the fires of the tired discourse surrounding Preston and her gross fetishisation of Aboriginal culture.

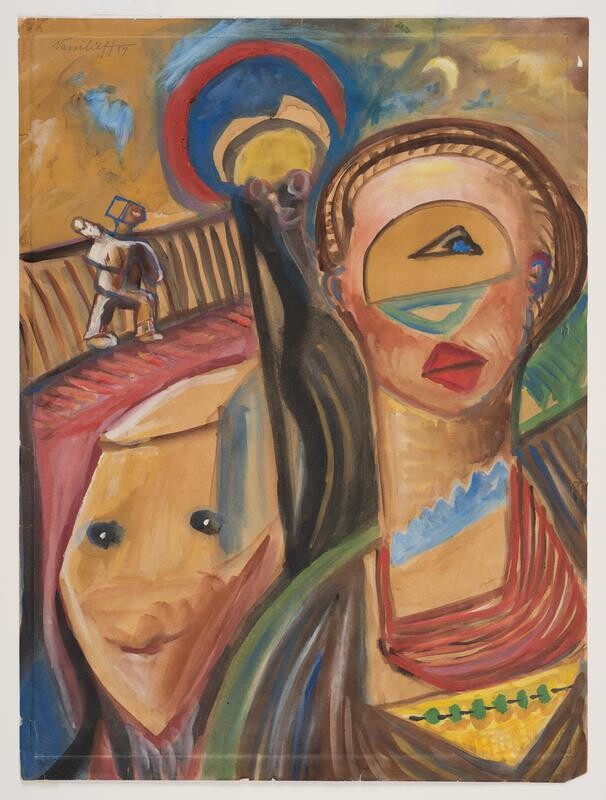

There are many excellent examples of what I deem above as “category A” works—that is, works that are interesting in their own right. A small watercolour by Danila Vassilieff, Going to a Fancy Dress Ball (1957), is so good. Painted just one year before the Russian-born painter’s death, it shows a surreal scene of four alien-like figures against a sloping built landscape. Why Vassilieff has remained such a minor figure in Australian modernism is a mystery. His sculptures, quarried by the artist himself from Lilydale marble, are amazing in their mythic creepiness. Also, the story of him having built his own house, Stonygrad, from rocks in Warrandyte adds to the artist’s bohemian backstory. Going to a Fancy Dress Ball is part of, I think, the strongest grouping, with three other works by Barbara Brash, Guelda Pyke, and Peter Purves Smith. Guelda Pyke’s Head of a Man (1950) is a collage of sharply angled brown, black, and tan paper cut-outs that conjure the movement and energy that the best modernist artworks encompass. And call me basic, but I also loved the small hang of photographs that included a Wolfgang Sievers portrait of writer Jean Campbell (1950) at home in East Melbourne. Though this photograph does not belong to the museum, it sits well with the three other collection photographs of female creatives—Ola Cohn, photographed by Hugh Frankland (n.d.), and Lina Bryans (n.d.) and Dorothy Braund (1973), photographed by Richard Beck.

Danila Vassilieff, Going to a Fancy Dress Ball (1957). Water colour and gouache, 40.0 x 30.1 cm. Courtesy of Castlemaine Art Museum.

Installation view of A Modern Turn, Castlemaine Art Museum. Photo: James McArdle.

This photographic representation of female modernists is just another strand in countless strands that the viewer encounters in A Modern Turn. But, for the most part, said viewer is left with more questions than answers. Why, for example, is there a vitrine squashed up against the wall housing two small paper works by John Nixon and three Klytie Pate ceramics? Nixon was influenced by European modernism and was a keen collector of ceramics, but his work was not historically modern, and the pairing of his works with the ceramics is not explained. Another vitrine is seemingly devoted to the theme of chickens but, again, takes the modern label with much liberty. Here we are presented with a stressful marriage of items including an undated “egg measuring machine,” a Margaret Pestell watercolour depicting a woman with an axe attempting to behead hens (also undated), and a Klytie Pate vase with roosters on it (1981). It gives hoarder energy.

In 2017, Castlemaine Art Museum was forced to close due to a lack of funding. But subsequent emergency private funding—$300,000 from an anonymous donor and $50,000 from the McFarlane family—allowed the museum to reopen. In 2019 Naomi Cass came on board as director. Cass, who was previously the director of Melbourne’s Centre for Contemporary Photography, was presumably brought on to bring the museum into better financial shape, possibly through targeted private funding. Which she did. At the close of the 2023–24 financial year, the museum reported a surplus of \$235,533. Presuming, too, that most of the museum’s collection is catalogued on its online database, it seems to me that a lot of the better artists in A Modern Turn are represented in it by only one or two works. And high-level analysis tells me that the museum, with its still minimal surplus, has not acquired new work in some time. This is a shame, because the best practice for the museum—which was established as a collecting institution of modern Australian art—would be to fill some gaps in the actually rather strong collection.

Installation view of A Modern Turn, Castlemaine Art Museum. Photo: James McArdle.

A Modern Turn tries to do too much and makes the viewer work too hard—though work hard enough and you will be rewarded. The exhibition would have achieved more by editing down the selection of works on display and tightening its scope. Plus, so many of the exhibited pieces were produced before WWII, so the post-war label is a little misleading. A better exhibition idea would have been to sketch the social milieu of Victorian modernism with Bell and Shore as catalysts. That is, A Modern Turn could have sketched the progress from category B works—that sparked the revolution, if you will—to category A works that got the job done. Indeed, deeper collecting of more obscure but interesting artists would improve future modernist-focused exhibitions at the museum. Get more Vassilieffs, for God’s sake. Any hobby collector will tell you that stuff like that comes up at local auctions regularly—and for cheap. But movement is afoot. A 2024 bequest from the late Joan Aspinall was given to the museum under the proviso that the money be used for acquisitions, including to “fill gaps in the art collection.” It will be up to the incumbent director (who will it be?!) and the board to decide what defines a gap.

Amelia Winata is a writer and curator based in Naarm Melbourne. She was recently Curator at Gertrude Contemporary. She holds a PhD in Art History from the University of Melbourne.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of Meridian Sculpture.