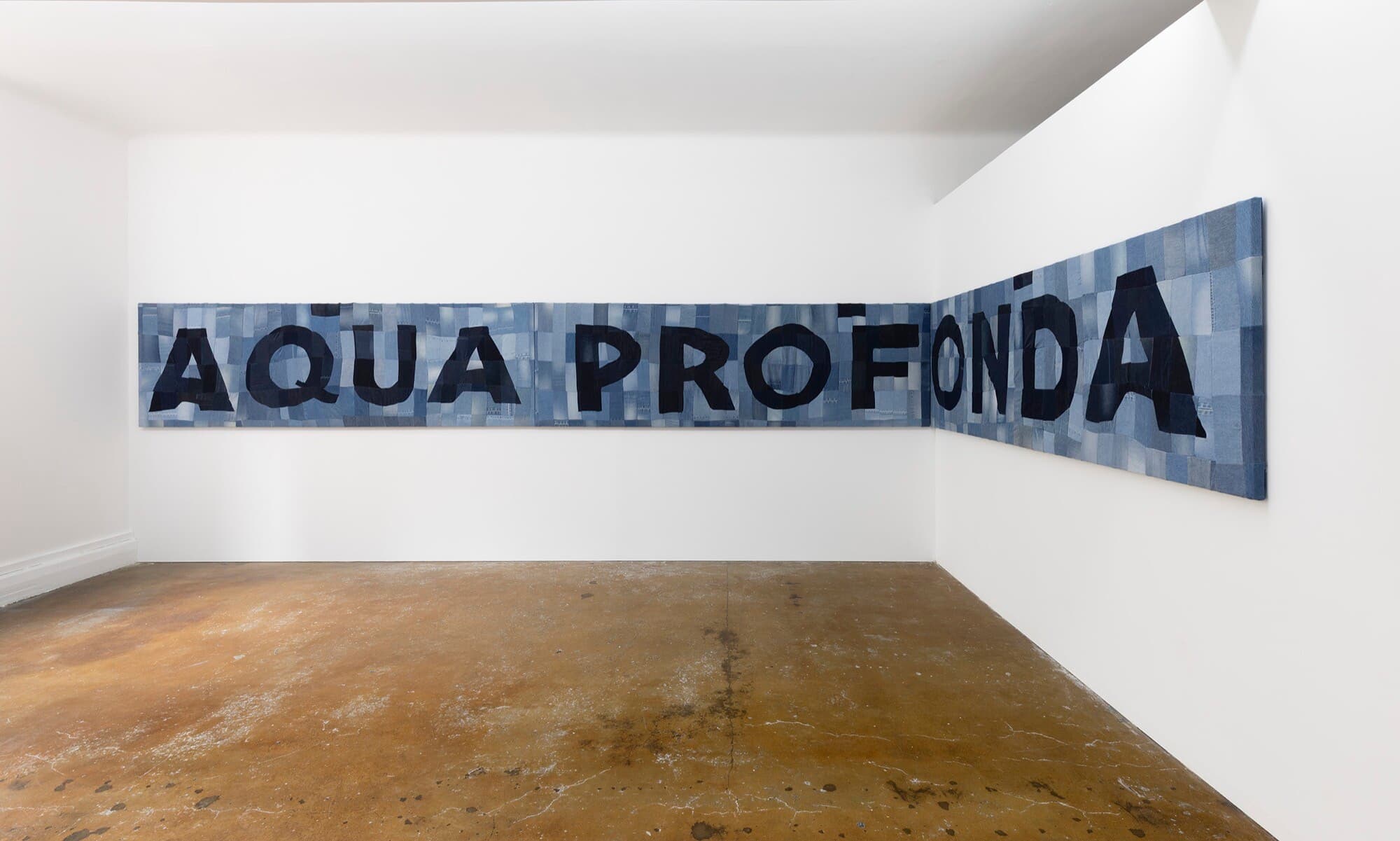

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

Beyond the Ballerina

David Wlazlo

After closing for a year of renovations, Wyndham Art Gallery—in downtown Werribee—re-opened in June to stage Beyond the Ballerina, a group exhibition curated by Dr Megan Evans and Olivia Poloni. The show presents visual art themed around dance: so no dance or performance itself. Specifically, the theme positions ballet as a cultural touchstone, a point around which the works pivot and inter-relate. The artists—Sally Smart, Zoe Croggon, Leyla Stevens, Joel Bray, Anne Scott Wilson, Anne Ferran, and John McCormick and Adam Nash—bring a diverse range of thoughtful, personal and surprisingly technological practices, each with a distinct response to the theme of dance, mediated through visual art.

The exhibition catalogue and wall text present the ballerina a bit like a fixed point of reference. The dance and movement-based works are (according to the texts) brought into dialogue with this European tradition. But what exactly is this thing called ballet that they’re speaking with? For me, the idea of ballet as a point of engagement is an interesting one. Mostly, because when I think about dance, I’m never thinking of ballet. Part straw-man “rigid tradition,” part foreign and alien cultural object, I wonder if the ballet is the exception to global dance practices rather than the rule?

Ballet and ballerinas are the last thing on my mind when I think about how it feels to be embodied and moving. When I’m forced to think about ballet, I think of competitive parenting, of SUVs negotiating a carpark that is far too small, of the first time many young girls experience their bodies as inadequate and lacking, despite popular culture building up the dream. As some kind of pinnacle of culture, it makes me think of an elitist tradition that devalues ordinary human bodies, that seeks to overcome us in our ordinariness. It makes me think of people who use French expressions randomly in English sentences. When I think about dance and movement, I think of stretching and bending my body. I think about my mirror neurons firing, feeling the movements I’m seeing. I think of participating, of getting up and losing all formality (beyond the increasingly rigid capabilities of my joints), of being up front at a rave, of giving zero fucks until my knees give out. The exhibition, however, does indeed do what it says on the box and “goes beyond” the ballerina. I do need to raise the idea that a centuries-old European tradition based in royal courts, and exported around the world via colonial networks, is invested in disciplining and judging human bodies for elite entertainment.

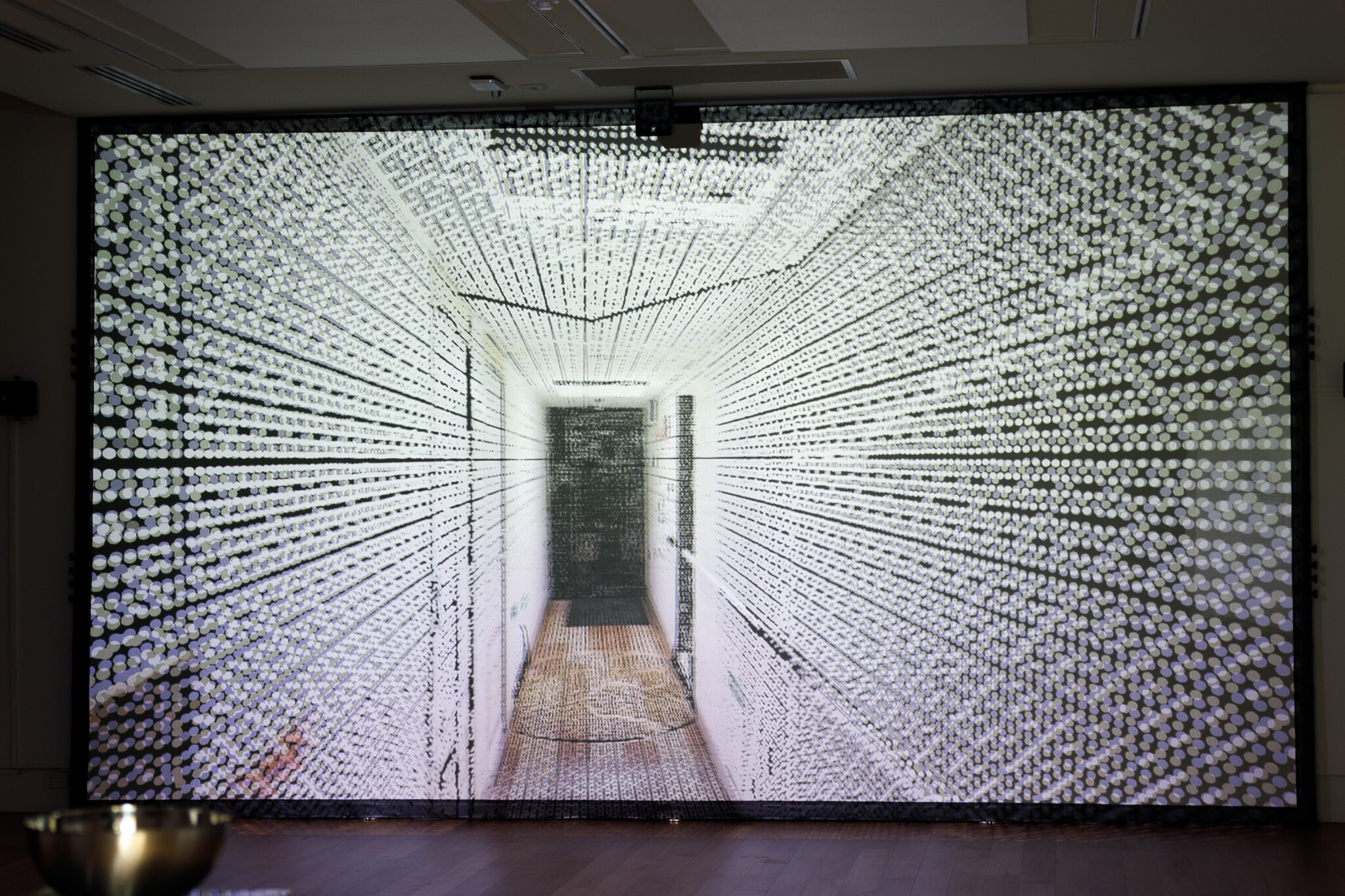

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s head back to the new gallery space, opening up to the right of a large foyer that’s fairly typical of local government civic centres: clean, accessible, lots of people passing through, most of them on errands that bypass the gallery. Within the exhibition, Sally Smart’s The Artist’s Ballet (Colour Wheel) (2025) dominates the main wall. Smart’s work is well known for her use of cut-up fabric, sewn-on collage, and montage drawn from early twentieth-century avant-garde movements Dada, Surrealism, and Constructivism. The work is a sublimation print textile (a kind of digital print on fabric) depicting an artist’s studio with lots of easels. It reminds me of life-drawing classes. Easels and figures are interspersed with cut-up and fragmented sewn on patches, and the edges are coloured as though within the curtain-like work there are curtains themselves drawn back to show the scene. Off to the side, two smaller works, The Artist’s Ballet Puppet (Dancer Brut) #1 and #2 (both dated 2021/25) hang from the ceiling. These figures are delicately constructed out of cut-up panels and then sewn, threaded, and balanced together like the single-stringed puppets they are. I can imagine these figures dancing in front of the wall-hanging in a kind of play, and briefly wonder why they aren’t displayed in front of the other work. Aside from this being a bit too literal a thought, the answer for me lies in the beautiful shadows cast by the puppets on the walls, which are certainly a highlight of the show. Maybe Smart’s work can cure me of my misgivings about the mainstream ballet? There are obvious echoes here of Dada theatre costume and collage, as well as Constructivist interpretations of the human body. I love this tradition. Perhaps dance was more obviously part of high-culture in the early twentieth-century, more of an obvious target for visual artists to re-interpret within the modernist paradigms? I’m thinking of Leger’s Ballet Mécanique (1923–24), but that title seems more an ironic reference to ballet than anything else.

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

Throughout the galleries, Anne Ferran’s large-scale photographic prints are spread out amongst the other works. The photographs are part of the White Against Red series (2018), created during an artist residency on the Finnish island prison Suomenlinna where, during the civil war in 1918, the victorious White party kept the Red party members prisoner. The photographs are of Finnish dancer Ervi Sirén, moving and bending while clutching felt panels in white, red, and what looks like a very light mauve or grey. I mostly know Ferran’s work from her photographic series, Lost to Worlds (2008), which were haunting photographs of the notorious nineteenth-century “Female Factory” women’s prison site in Tasmania. Covered in earth, mounds, and lumps that appeared pregnant with marginalised, rejected, and incarcerated women, the thought of Ferran creating work within and around a historical prison on the other side of the world seems perfectly apt. The White Against Red series seem to have been created in reference to the site of incarceration, but it also seems to have a certain historical affinity to the constructivist leanings of Smart’s work: the colours in the title, the histories of communism, the industrial materials. The title could be an early formal experiment in Suprematism. The mood is less festive in Ferran’s work though: the dancer—striking red hair hanging down—seems to be in the process of gathering up the pieces of felt and fabric as though there are some accidentally left behind, as though (maybe) this is not a dance but an expression of mourning or residual anxiety.

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

Zoe Croggon’s work nearby also seems captivated by the folding of materials, both in her collages and the photographic prints. Croggon’s works are small to medium in size, hung as an arrangement, salon style. Fragmented figures are cut off by the edge of their paper, interrupted by photographic copies of what looks like satin; magazine pages are folded open to show broad colours. The only two complete figures are a dancer in black and white, gown flowing, and a naked person doing a forward bend. The effect is something like a stylish fashion illustration mash-up. The works are the most formal in the show—or at least neck and neck with Smart’s—in the classical sense of that word: their concern seems to be about broad colours, shapes, fragmented representation, and the surface of the picture plane. There is a lot there, but not in a lexical easy-to-put-into-words way. My favourite works, Miranda (2016) and Eclipse (2021), are at the bottom of the grouping and appear to be some kind of cake-ish dream sequence. These two works seem flatter than the others, but with smooth colouring and an almost marzipan quality. Miranda features a dark negative space that becomes figure by drooping through a sharp flesh-tone hook. Eclipse carries a similar fleshy tone with a vertical band of ribbon-like shapes swirling in the centre as though bursting from some bodily fold. In spite of this viscerality, Eclipse’s cake-ishness is an echo of the venerable icecream cake the Streets Viennetta. And (while I’m going along with this seemingly unstoppable thought) there’s also something very ballet about the Viennetta.

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

Nearby is a series of three single-channel videos by Anne Scott Wilson, playing back-to-back on the same screen. The videos are titled EveryDay I Wait (En Équilibre), Part 1, Everyday I Wait (En Mouvement), Part 2 and Every Day I Wait (À Terre), Part 3 (all 2025), and they show black and white films of Lisa Bolte, former Principal Dancer at the Australian Ballet, going through some repetitive and athletic movements that show excellent skill and strength. These works are the first I’ve seen that have an explicit relationship to ballet, and after having already made my feelings on the matter clear earlier it’s going to be hard for me to write meaningfully about the work now. But I will try, wearing my bias on my sleeve. The dancing itself is simple: Bolte moves, breathes, and occasionally—at the end of a particular sequence—looks and smiles to the camera. There is some fragmentation, such as an extended focus on her shoulders and back. There are also, inexplicably, some colourful butterflies added to the video. These insects appear to fly and move across the surface of the video, and I’m not sure what to make of them. Are they a metaphor? If so, of what? Fragility? Beauty? It’s quite jarring because the footage of Bolte has an almost realist quality: you can sense a tangible corporeality there, a real, fallible, powerful human, beyond all the misgivings I already have about traditional ballet. But then the butterflies take this all away. I later find out that the artist is also a former ballerina and is interested in the ways dancers cope and continue to grow with their aging bodies. This is a worthy concern: how do we face aging gracefully, especially in a field seemingly dominated by youth and pliability. Bolte looks strong and in her element, but I’m not so sure about the butterflies in this work.

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

In an adjoining room, Scott Wilson has a second work, Lift (2025) which features the same elements as the previous work (insects included), but with the addition of extra screens, an audio track, and an interactive element. The sounds and additional screens are of a ballet studio: instructions being given, floorboards creaking, formal exercises being undertaken. The work allows and encourages viewers to stand in a particular spot, where a motion sensor device will put their silhouette on screen with the dancers projected in front. It’s a fun and joyous interactive piece—you’d bring your young kids here—different to the artist’s works in the other room. The playful engagement of Lift, compared to the pensive reflection of the other works (albeit both confused somewhat by the butterflies), gives me mixed messages about what looking back at a career in the ballet is like: Bolte, the master ballerina, is clearly one of the exceptional dancers in the country, but then the playful, almost child-like, perhaps nostalgic, interactive engagement suggests something else. Intriguingly, the technological element in these works seems to add another message to the mix, in addition to the butterflies across the frame, the movement sensor, and the dancer. There’s a kind of bittersweet feeling to take all these ideas, mixed-in together, that I just can’t shake off. It’s the butterflies: they seem to be there for either a clumsy metaphor, or as a foil for some kind of trauma. I’d only bring my kids here if they were prepared to listen to a lecture on body-positivity on the way home.

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

Back in the main room is Balinese-Australian artist Leyla Stevens’s work Patiwangi, the death of fragrance (2021). This dual-channel video employs dance and museum archives in an examination of traditional Balinese dance in comparison to museologically preserved art objects in an un-named institution. The left screen shows tracking shots of a museum archive, gloved hands removing artefacts from protective wrappings, and chroma key (or green screen) effects of art objects composited on top of everyday museum items such as crates and trolleys. The screen on the right shows two dancers engaged in a kind of exchange of movements and ideas. The women lead each other through certain gestures and poses, only to cycle through to a point where they change places, and different things are taught or shared with the other. There’s a strong sense of the dualities at work here: the museum as a site of fixed and preserved cultural objects (for they are all Balinese cultural objects in the left screen) and the reciprocal and open cultural exchange between the dancers (one of whom appears western, and the other Balinese). The dancers move in contemporary forms at times, but at others they are quite restrained. Perhaps the traditional Balinese dances, which are full of codified gestures and expressions, are rigid forms in parallel to European ballet? They seem to have developed around about the same time (the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries), so they both have the same historical weight behind them. Of course there are cultural differences, and I don’t want to generalise. In spite of these dense concerns, the work is executed with an engaging lightness, tenderness, and humour: occasionally, the green of the green screen reveals itself, and the fourth-wall is momentarily broken.

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

Off to the side is a smaller room; on the far wall, is Wiradjuri artist/dancer Joel Bray’s three-channel video GIRARU GALING GANHAGIRRI (The Wind Will Bring the Rain) (2021). This work shows a dancer, outdoors, moving through space while applying body paint. The paint becomes the video’s chroma key, and through these markings on the dancer’s body another place is shown. As the dancer moves, so too does the land seen through his body. In the wall text, Bray describes how making this work on Boonwurrung and Wurundjeri land helped him feel connected to his Wiradjuri home through the feeling of connectedness to the cycles of nature. It’s a very compelling artwork, but there isn’t really a narrative as far as I can tell: the dancer walks through rivers and fields, applying paint to his body, and through this paint can be seen other landscapes, including some farm-like places with forty-four-gallon drums lying around haphazardly. I was fully immersed when watching it. Only when I went away and thought about the chroma key and the landscape through the dancer’s body did I realise how literal the work was. Or, rather, I realised how hard it would be to say something more meaningful about it than a description. What I mean is this: I sat watching this piece and I was mesmerised. The figure swirls through the amazing landscape, both beautiful in their own ways. For the artist, the idea seemed to be to perform outdoors as a way to connect to distant Country, as though his body had or embodied that connection. Through the chroma key, this is quite literally what happens in the work. I want to say that the work does more than what it quite literally does, but perhaps this is the result of chroma key when it’s put to expressive use? Maybe I lack the right words—or even the right—to ask the work to do more than what it does. I’m clearly going around in circles here.

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

Away across the foyer, in what looks like a purpose-built screening room (but far away enough to not obviously be part of the gallery), is the final work in the show: John McCormick and Adam Nash’s Last Dance Orange Roughy (2022). The video is an immersive and technological representation of the last voyage to Antarctica of the ice-breaker RSV Aurora Australis. The artists were present on this final voyage and recorded the ship and the crew via lasers and photogrammetry scans. Combined, these form a digital 3D model. Entering the room you therefore must also pick up some 3D glasses. The large projected video shows a semi-transparent digital representation of the ship in motion. The walls and stairs are transparent planes of dots or datapoints, and occasionally figures appear, either to dance in unison or conduct some kind of business-as-usual activity aboard the vessel. The camera circles and flies through the ship, and the deck becomes a dancefloor. In other moments, the swaying figures of intensely populated data points (the crew members) appear to run haphazardly through the corridors or sway side to side. There’s a subtle distinction between dancing and simply moving with the ship, and on occasion figures fall through the floor or seem to stand below it. I really enjoyed this work: the 3D effects weren’t overdone, the representation of space through the dots of data was visually engaging, and the narratives blended the poetic dancers with the ship workers effortlessly. Perhaps this is an antidote to my ballerina-phobia: a kind of tech-bro ballet, one that tries to look forward into mediated dance while at the same time honouring a period of scientific research.

Installation view of Beyond the Ballerina, Wyndham Art Gallery, 2025. Photo: James Henry.

I still have the same misgivings about the ballet, but I realise that this is only when people claim it as some kind of apex of human movement. The works in Beyond the Ballerina present a diverse range of art practices that are engaged with dance. They don’t—I’m glad—all engage in a direct dialogue with the ballet as though it were the measure of all things dance. The approaches are varied: Smart and Croggon are invested in formal fragmentations of the body within pictorial space, Ferran and Stevens respond to sites of historical trauma or museological preservation, Bray is concerned with a way to engage with personal connections to a particular Country, Scott Wilson is (beyond the butterflies) concerned with a tradition and a profession (and what happens when you retire), McCormick and Nash offer a technological memorial for a vessel involved in scientific research (as well as its retirement). Summarising it like this, there seems to be a strong backward-looking theme to these works: some appear deeply thoughtful and invested in this past, while others work toward breaking through it. Leaving ballet off to the side, or at least alongside (where it belongs), there are clearly more interesting traditions and approaches to human movement in visual art.

David Wlazlo is an artist and writer who lives on Wathaurong country.