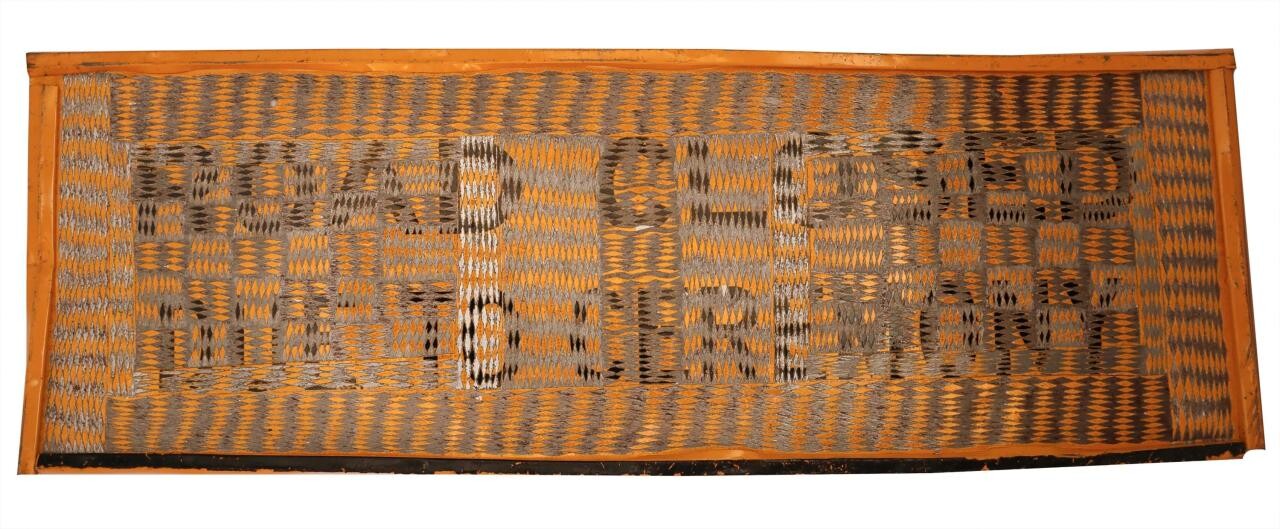

Installation shot, Ŋjäṉarr—Tongue of Fire, courtesy Tolarno Galleries.

Wanapati Yunupiŋu: Ŋäṉarr – Tongue of Flame; Yolŋu Power: The Art of Yirrkala

Rex Butler

Anthropologist Howard Morphy first spent time among the Yolŋu on a series of field trips between 1973 and 1976. He first wrote about Yolŋu culture at length in his Journey to the Crocodile’s Nest in 1984. But it is in his Aboriginal Art of 1998 that he notably took up the rarrk painting that characterises the art of central and eastern Arnhem Land. He describes in detail there the covering of the surface of the bark with a red ochre wash, then the outlining of a design in either yellow or black, and finally the slow filling in of the rest of the surface with delicate cross-hatching applied with a brush made up of only a few strands of human hair. The effect, he writes, is a kind of shining or scintillation, in which the eye is unable to stop or pause on any particular feature before moving on. For Morphy, this is an expression of the “power of the ancestral beings incarnated in the object,” and the work he chooses to evidence this is Manydjarri Ganambarr’s ochre on bark Shark (Djambarrpuyngu Maarna) (1996), in which we see a shark caught in a fish trap in the bottom panel dissolve into glittering crystals in the upper panel to escape its hunter: “His body is incorporated within the geometric design that surrounds him, signifying his transformation into a more spiritual force.”

Morphy speaks of the work’s bir’yunhamirri or “shimmering brilliance” to point to the Yolŋu desire to “produce aesthetic effects that communicate to artists of other places and times,” but it is in his “From Dull to Brilliant: The Aesthetics of Spiritual Power Among the Yolngu,” written some nine years before in 1989, that he most fully addresses this. In “From Dull to Brilliant,” Morphy explores the implications—amongst them his own shift from anthropologist to art historian—of considering Yolŋu bark paintings “art” and evaluating them in terms of “aesthetics.” He insists that “art” and “aesthetics” are not exclusively Western concepts, and that the Yolŋu are self-consciously making, among their other uses for and understandings of what they are doing, art. Again, the word Morphy uses to characterise their work here is bir’yun or “brilliance” or “shimmering.” And here too, in line with his argument, this bir’yun or brilliance reaches out beyond its original circumstances to speak to outsiders like Morphy. Here is Morphy on the way that these ritual and ceremonial works break their tribal boundaries in a kind of cross-cultural glow or halation: “The shimmering effect of the cross-hatching, the appearance of movement, the sense of brightness, are all attributes of Yolgnu art that can be experienced independently of any other knowledge about Yolgnu painting.”

Of course, as we read Morphy evoking some original bir’yun or brilliance and wondering what happens to it when it crosses over to other cultures, we cannot help but think of Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), in which he similarly seeks to predict the fate of the “aura” of such ritual Western arts as Ancient Greek drama in an era in which they are reproduced and, like Morphy’s evocation of seeing sacred Yolŋu designs out of the corner of his eye when he wasn’t meant to, the audience is no longer co-present with the original artists or performers, but as in the cinema sits in the dark alone watching a copy without the actors being physically present. Here are Benjamin’s famous lines concerning aura and its belonging to that original moment of the making and reception of the work: “One might subsume the eliminated element in the term ‘aura’ and go on to say: that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art… We might generalise by saying: the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition.” (Indeed, following on from Morphy, such later writers on Indigenous art as John Kean in his recent Dot Circle and Frame: The Making of Papunya Tula Art (2023) refers alternately to the “bir’yun,” “flash of light” and “refraction, iridescence and interference” with regard to that “original” moment of the Men’s Painting Shed in Papunya, in which there seemed to be an absolute coincidence between the making of the work and its first reception.)

Gurtha (Road closed for Ceremony), 2021. Medium etched road sign. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with funds donated by Christopher Thomas AM and Cheryl Thomas, 2022. © Wanapati Yunupiŋu.

“The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” is undoubtedly one of the most reproduced, commented upon, we are tempted to say “auratic,” essays about art in the twentieth century. Its diagnosis of the “withering” and even disappearance of the aura cannot help but strike us as astonishingly predictive of the fate of all artworks today, not just theatre, but the visual arts, novels, poetry, and even cinema itself. It is so obviously correct and ubiquitously true that it is barely cited anymore in the age of the internet and virtual reality, in which “aura” appears entirely to have vanished with seemingly no connection between the work of art and any—not just original—audience. But of all the thousands of commentators on the essay—which has itself become something of a medium of “mechanical reproduction” in academe—there is one that has always struck me as more brilliant and insightful and subtly subversive of the original than all the others. It is the American deconstructionist literary scholar Samuel Weber’s “Mass Mediauras, or: Art, Aura and Medium in the Work of Walter Benjamin” (1996), and the extraordinary provocation he makes there is that the “brilliance” or “brightness” of aura is not some original presence or co-presence of the work with its audience that is then threatened or done away with by its reproduction, but something that arises only retrospectively through its very reproduction. In other words, aura is not something intact and unchanging, but always fleeting and disappearing, coming about only as a brief spark or outburst in its very being done away with, as it were between reproductions, in what Weber calls the “inter-mediary.” Put another way, “aura” only exists during Benjamin’s diagnosis of its disappearance. This is Weber in “Mass Mediauras”:

Distance and separation are therefore explicitly inscribed in the scene, or even the scenario, of the aura, and that from its very inception. In this sense, the ‘decline’ or ‘fall’—der Verfall—of the aura would not be something that simply befalls it, from without. The aura would from the start be marked by an irreducible element of taking-leave.

Needless to say, I no longer remember when I first saw one of Yolŋu artist Wanapati Yunupiŋu’s street signs with the words “ROAD CLOSED—DUE TO CEREMONY” on it, but I do remember immediately thinking that it was the most captivating and compelling work of Australian art I had seen since Emily Kngwarreye’s yams. And I do remember thinking of Weber’s essay as a way of reflecting upon it myself. The surface of the metal sign was ground off in a series of crisscrossing, rarrk-like planes with an small rotary grinder to produce a coruscating burnished surface through which the letters appear to be distantly glimpsed. The message of the sign indicates a kind of dead end or injunction not to look at the same time as we cannot take our eyes away. And the fact that the sign had apparently been found after lying dusty and abandoned beside a road around Yirrkala tells us everything about the equally “abandoned” Aboriginal communities in north-east Arnhem Land, colonised and thrown to the side by the gigantic multinational mining companies extracting wealth from Aboriginal land. And, most notably and brilliantly, Yunupiŋu’s art comes out of the very impossibility of continuing that “original” moment of rarrk painting on stringbark gumtrees, as seen in such artists as Mawalan Marika, Galuma Maymuru and Wanapati’s own father, Miṉiyawany Yunupiŋu, in again something of a decline or even end of an Indigenous ritual tradition, perhaps because of the continued pressure on Aboriginal communities if one is an anthropologist, or the running down or exhaustion of that rarrk tradition of painting on bark if one is an art historian. Put simply, the road is closed and the ceremony is not able or permitted to be seen ahead.

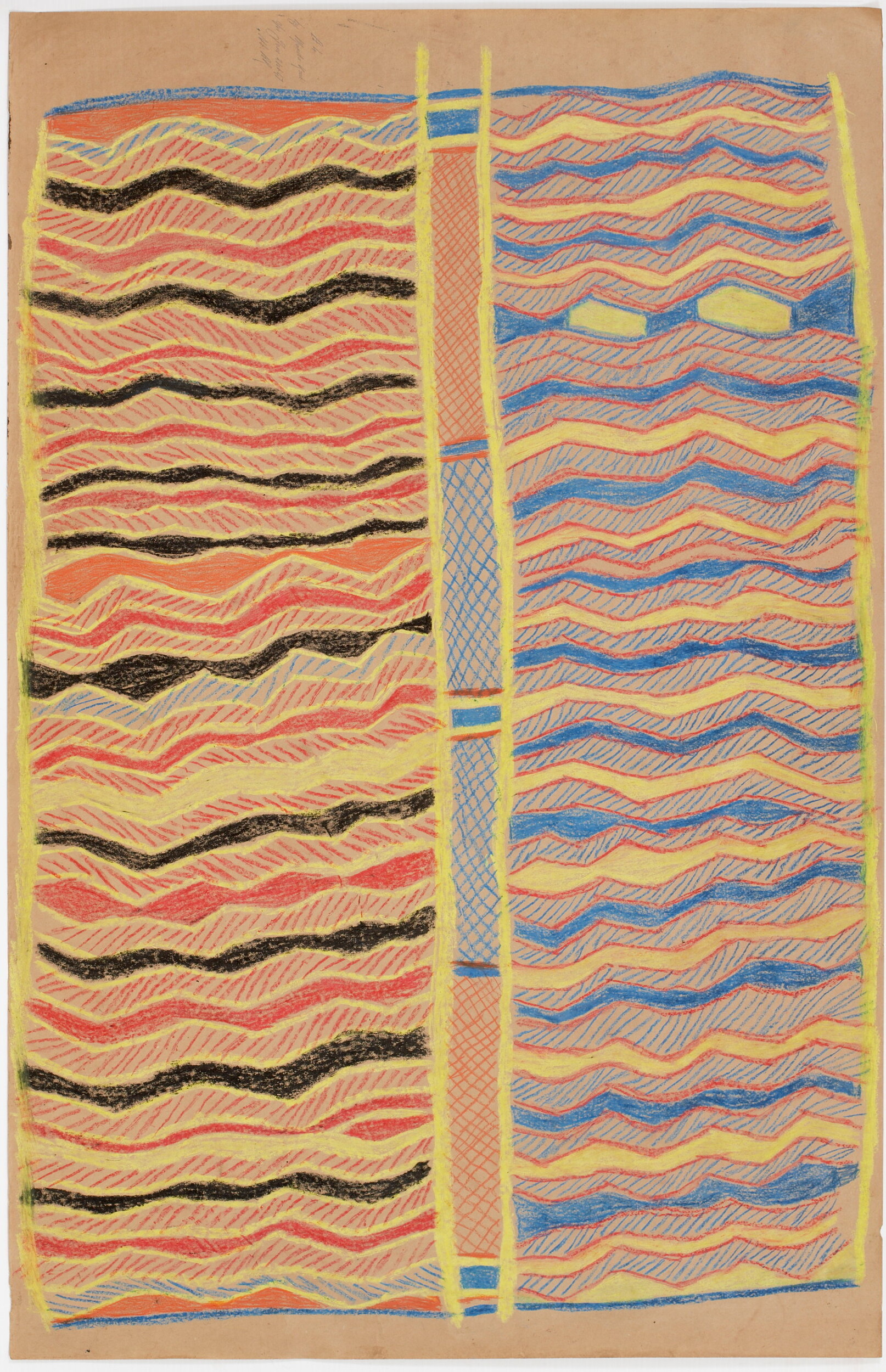

Mundukul Marawili Fish trap at Baraltja 1947, lumbar crayon on butchers paper, 115 x 74 cm, Berndt Museum, The University of Western Australia © Estate of the artist, Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

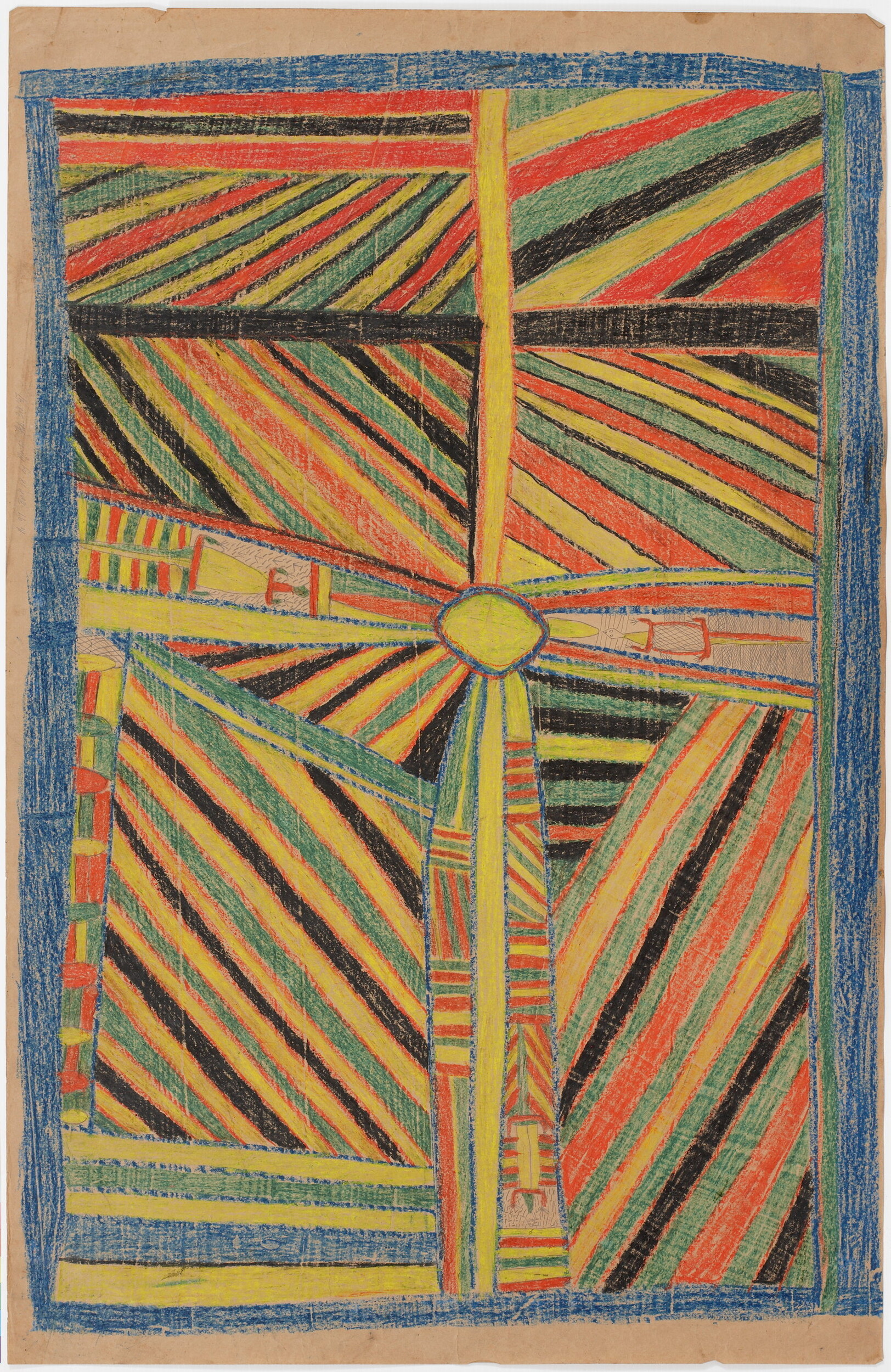

Mowarra Ganambarr Djaŋ’kawu created waterhole on Ḏäṯiwuy estate 1947, lumbar crayon and graphite on butcher’s paper, 115 x 74 cm, Berndt Museum, The University of Western Australia © Estate of the artist, Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

But then, as Weber predicts, out of this apparent decline or disappearance, something brilliant and mesmerising, something “auratic,” arises: Yunupiŋu’s cross-hatched street signs. The closed road, the painting we cannot look at or through, is the ceremony. And, indeed, Yunupiŋu is only one of a number of Yolŋu artists working in this new medium, or we are tempted to say inter-medium, or even if we follow my current art history hero Rosalind Krauss, post-medium. In fact, it was Gunybi Ganambarr, the 2018 Telstra Aboriginal and Torres Strait Art Award winner, who originally taught Yunupiŋu the method. There are Wurrandan Marawili and W Waṉambi, who were both in the recently closed Yolŋu Power exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. There is Gaypalani Waṉambi, whose Burwu or Blossum won the 2025 Telstra Aboriginal and Torres Strait Art Award. But—and this was the brilliant provocation of including a younger generation of steel grinders along with such apparently “original” first generation practitioners as Mowarra Ganambarr and Gumuk Gumana in Yolŋu Power—even those “originals” were not simply original, the expression of some intact and unchanging tradition, but already subject to a certain modernist loss of aura, a certain demand for reproduction, a certain passing outside or beyond some notional ritual or tribal context or occasion. We might think here of the several versions of Djanj’kawu or Creation Story (1959) by Mawalan Marika reproduced in the catalogue, or the linocuts by Banduk Marika and crayon drawings on butcher’s paper by Bunuŋgu Yunupiŋu, Gumuk Gumana, Mowarra Ganambarr and others in Yolŋu Power.

The brilliance of Indigenous art—like all art—arises in its passing beyond the original circumstances of its naming and reception across to a future audience that cannot know of them. Manydjarri Ganambarr, Wanapati Yunupiŋu, Samuel Weber and perhaps even Walter Benjamin are all saying that it is nostalgic to think otherwise (and, again, the truly challenging thought is that Indigenous culture has always been like this and it is only our own colonial feeling of guilt over what we have done to Indigenous people that makes us want to think it is otherwise—and often exhibitions of Aboriginal art seek to deny it still).

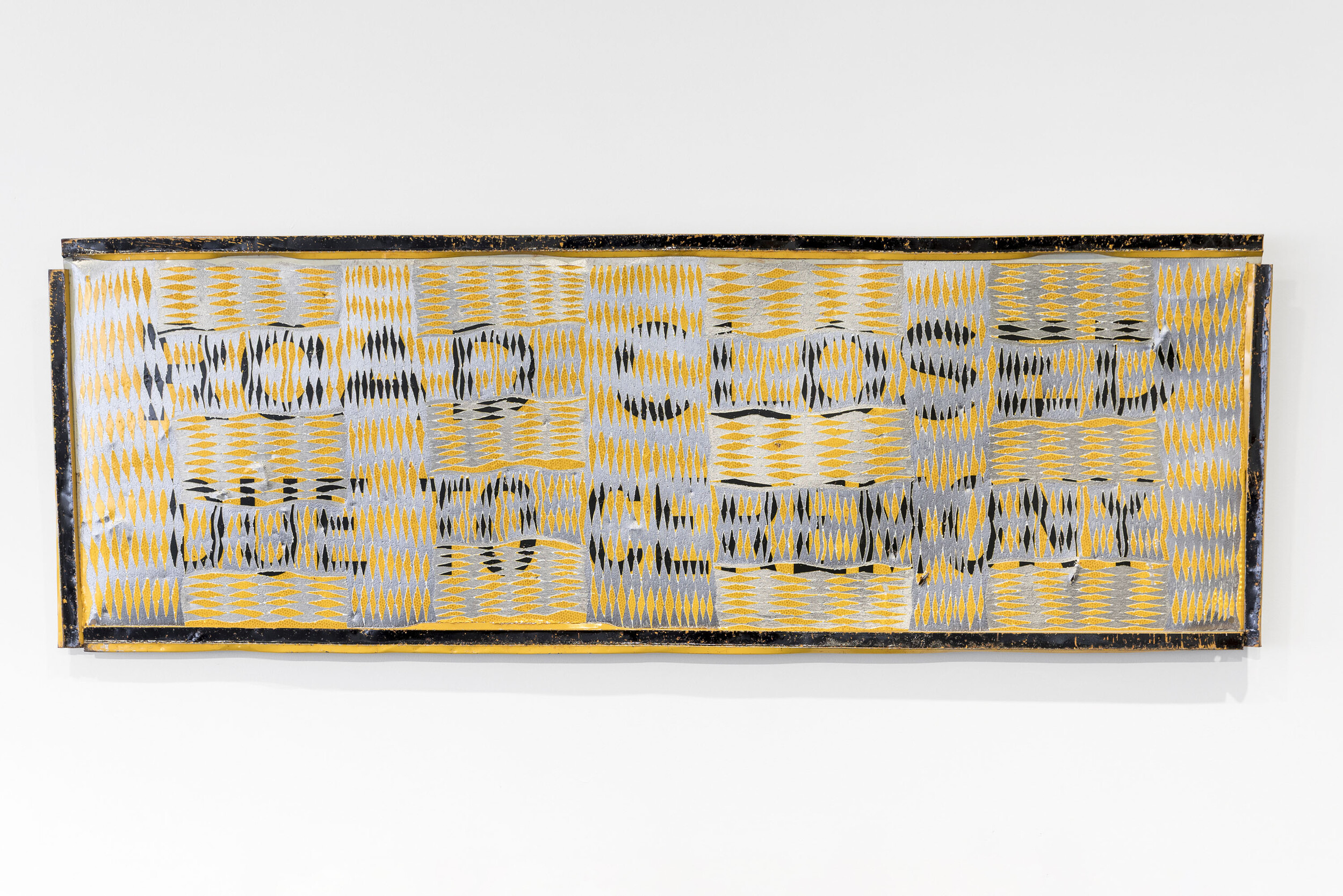

Installation shot, Wanapati Yunupiŋu, Gurtha (2025), etched stringybark, courtesy Tolarno Galleries.

Finally, this is the coup—as though already foreseeing all that we were going to say—of Yunupiŋu in his latest show at Tolarno Galleries. In some ways returning to that “original” method of inscribing a rarrk pattern on the bark, in a series of works entitled Gurtha or Fire he uses an small rotary grinder to carve cross-hatched markings into stringybark. They end up looking like ritual message sticks, and the message Wanapati might be telling us is that “tradition” arises only after its destruction. Or, put otherwise, it is not a grinder that comes after that marwat (hair) brush, but before. Art, great art, destroys what it preserves. Or, to put it the other way around, it preserves what it destroys. It reminds us of what is lost, even as it is doing away with it. Like Wanapati’s street signs, you cannot look away, even though there is nothing more to see. And what you would see, if you could, is that it is all over, that there is nothing more to see, that the road back to the past or ceremony is closed. (But not to worry, Yunupiŋu makes new versions of “ROAD CLOSED—DUE TO CEREMONY,” “REDUCE SPEED,” and “PREPARE TO STOP” for this show.) That’s the harsh lesson of Indigenous art in Australia today, as it has been of all art. It’s been brilliant in its passing away, its ceremony commemorating the end of ceremony.

But at least for the next several weeks it is there to be seen at Tolarno Galleries. Go there and be blinded. Just as we always have been by Yolŋu power. But remember to look out of the corner of your eye. The gallery is open due to ceremony, and it was wonderful to be welcomed at the opening by the artist, his mother and his father singing it all to us.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.