Victoria Todorov, The Bipolarity of Output (AUX)

Amelia Winata

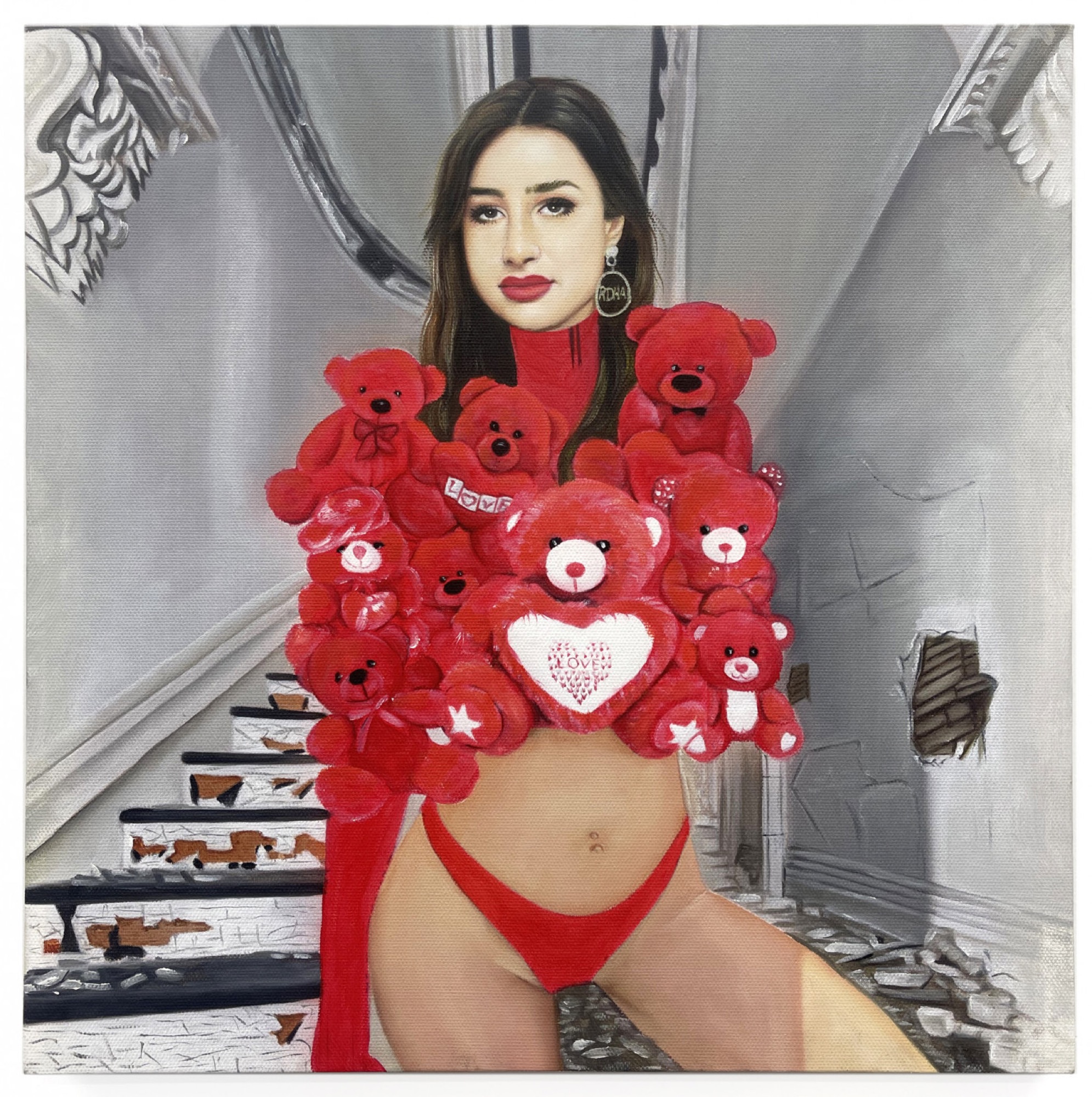

Elizabeth watches over patrons is an oil painting by Victoria Todorov currently on display in her solo exhibition The Bipolarity of Output (AUX) at Discordia. The painting depicts Discordia director, Elizabeth McInnes, dressed in red underwear and a red long-sleeved t-shirt adorned with teddy bears. Painted in a hyperrealist manner, the work is glossy and represents McInnes as hypersexualised—her plump lips draw the viewer’s attention to her face and, specifically, her sultry stare. The backdrop, a decrepit staircase and hallway, makes the image look like something out of a fashion editorial set in an alternate-universe Nicholas Building. In many ways, Todorov’s painting of McInnes is representative of the Instagram hyper-glam influencer framework. This is a structure that the artworld, far from being a vacuum outside of it, is inextricably linked to. Maybe it’s a hangover of modernism that we continue to expect art to offer some aspirational alternatives when, in fact, we might do better to consider it through the lens of aspirational imitation.

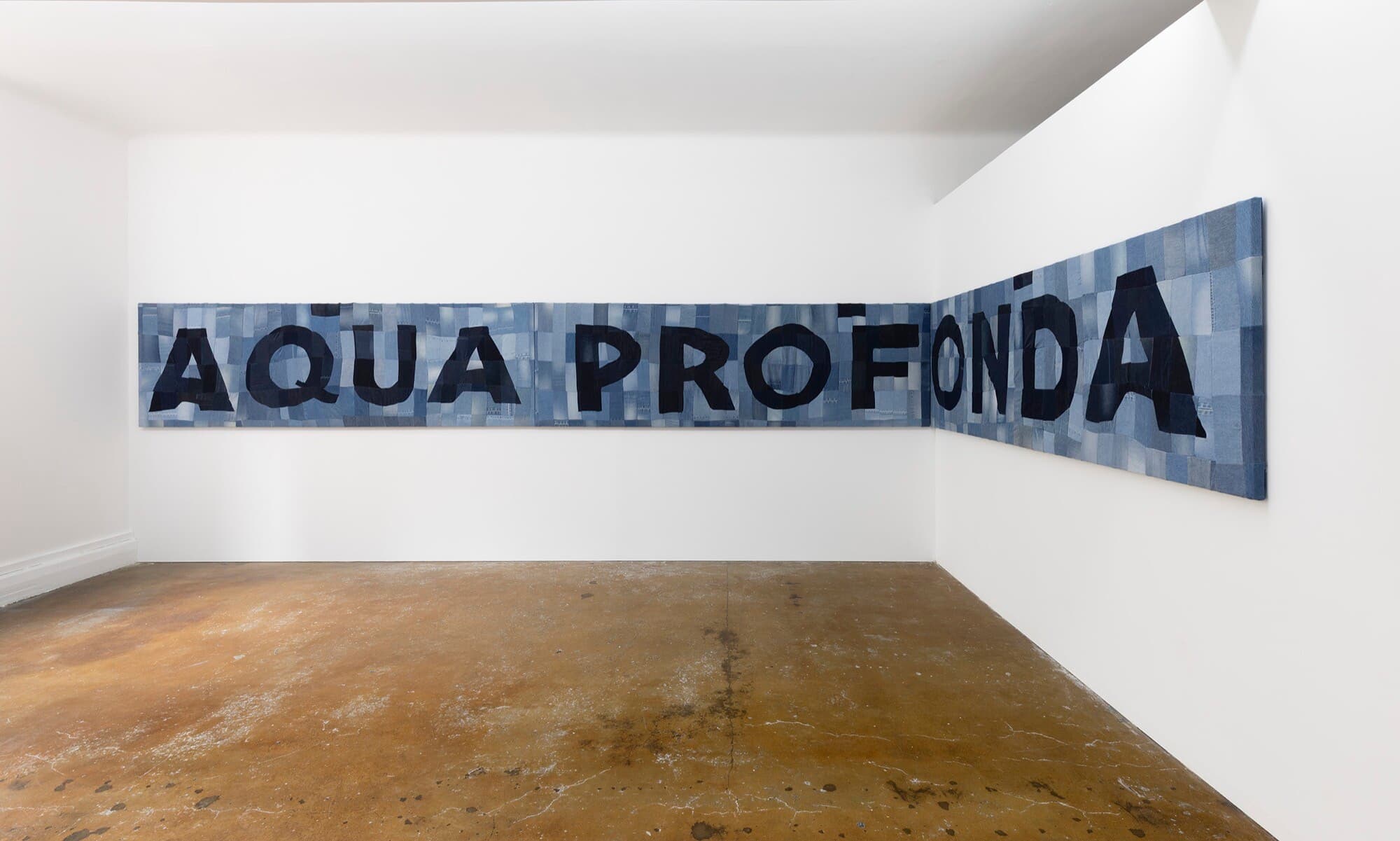

The Bipolarity of Output (AUX) is comprised of a suite of hyper-real paintings and two assemblages. If outsourcing is the practice de rigueur of the post-internet age, then Todorov’s painting production method closely follows this outlook precedent. To make her paintings, Todorov creates either physical or digital collages and sends them to a factory in China that specialises in old master reproductions. The Bipolarity of Output (AUX) is currently installed at Discordia but with the Melbourne lockdown extension looking inevitable, you probably won’t ever get to see it. Neither will I. This review is based on a press pack sent to me by the gallery and a series of email and Instagram conversations with Todorov. While I can’t speak to the specific install of Todorov’s exhibition, her practice—entrenched as it is in images—is an ideal example through which to consider the precarity of our present moment. Her use of the word “bipolarity” perfectly encapsulates that mood. Beneath rather homogenous surfaces are a series of competing tensions (just as recent anti-lockdown protests were the meeting point for neo-Nazis and yoga mums). The Bipolarity of Output (AUX) and, indeed, Todorov’s oeuvre to date, represents a dialogue between satire and authenticity, all mediated by an inside/outside tension.

Todorov has said that she feels outside of the artworld. She rarely attends openings or events and did not study art, coming instead to her practice after studying fashion at RMIT. But if Todorov feels she is not embedded in the art scene, then she is simultaneously very much present. A recent collaboration with Melbourne cool-kid Spencer Lai, Bitch Biscuit (to be staged at Bossy’s Gallery post-lockdown) represents an in-the-know power allegiance. Prior to its postponement, Bitch Biscuit was the opening everyone wanted to be seen at. But, more than this collaboration, it can be said that Todorov is deeply entrenched in the art scene by way of her Instagram presence (@victoria_todorov), where she posts almost daily. Thinking about the inside/outside tension, I am reminded of Michael Newman’s assessment of boredom in relationship to distraction. Theorists tend to agree that boredom emerged in tandem with the industrial revolution, proliferating in the perfect mix of clock time and extra leisure afforded by the regimented workday. Despite taking a greater hold on society throughout the twentieth century, Newman argues that boredom has now been replaced by distraction—we may still be bored but we don’t know it as such. “That boredom today might be ‘a thing of the past’ raises the question of the loss of the outside in the context of the economisation of everything and the totalisation of distraction,” he writes. It is this totalising force that confuses the logic of inside and outside, spoken of by Newman, that Todorov’s works get to the heart of. Todorov’s images engage in the contemporary trade in distraction. Garish, glitzy, bright and glossy, they offer consumer imagery—a Balenciaga double B logo, a Gucci bee (Caviar on shell, not metal, 2021)—that fashion-conscious viewers’ brains have been trained to recognise in the blink of an eye.

Bimbos and himbos are a common theme in Todorov’s work, deployed in her consideration of authenticity. In Self Made, C.E.O. (2021), we see the socialite Joselyn Wildenstein flanked with a strange assortment of items united by their sense of extravagance, both real and unreal. A Rolex watch is perhaps the only truly luxury item depicted, while a cheap gold sequined bow tie represents the image of indulgence but within the framework of kitsch. Wildenstein, AKA the Catwoman, is known for her extreme plastic surgery, was widely regarded as a failure, having married a wealthy man, spent his money on her various surgeries and eventually filing for bankruptcy. In choosing to represent Wildenstein in not one but two paintings, Todorov seeks to revise this dominant narrative surrounding the socialite: to her, Wildenstein is the embodiment of a self-made, authentic woman who reached these ends by way of artificial construction.

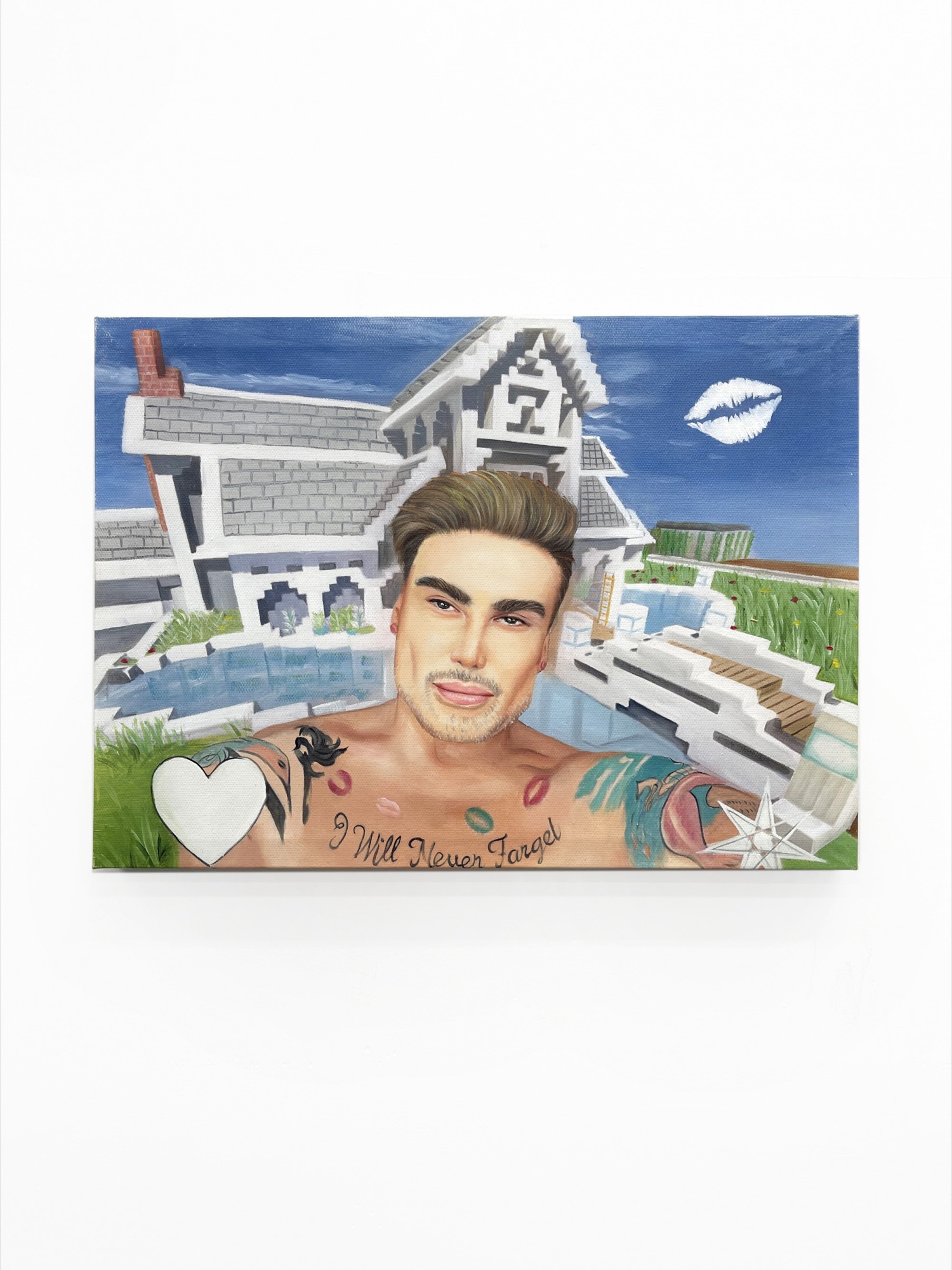

Traditionally, the bimbo was defined as a woman with minimal intellectual abilities who uses her sexuality and looks to pursue men. The blond, big-lipped, huge-titted woman is the ultimate example of this—think Anna Nicole-Smith. In recent years, the bimbo has been claimed by twenty-somethings to invert expectations about gender and sexuality, gaining traction on social media amongst left-leaning “youths”. The subject is no longer strictly female. Himbos have entered the scene as antidotes to toxic masculinity. And people identifying as non-binary are subscribing to bimbo culture—thereby defying the gendered logic of the original term. From one work to the next, Todorov’s audience sees the historical topography of the bimbo reveal itself. After Wildenstein, we come to Future Rubiks Cube (2021), which depicts an unidentified, tattooed himbo who stares with kind eyes out into the distance. He has been collaged against a palatial looking house replete with moat that was probably lifted from a video game. Despite his artificial appearance, this is a real person, “an Eastern Euro botched guy,” says Todorov. In our journey through the bimbo/himbo evolution, we might argue that the portrait of McInnes represents the bimbo’s full-circle—she is now an intelligent, enterprising and independent woman who does not suppress her sexuality.

The major dilemma of bimbofication is that it is simultaneously anti-establishment but pro- consumerism. For as influencer and self-proclaimed bimbo Griffin Maxwell Brooks states, “the bimbo exists at the aesthetic intersection of tackiness and luxury”, albeit with a tongue in cheek humour that suggests the satire of bimboism. Todorov leverages this conflict to her advantage: the impasse of bimbo culture is representative of the myriad conflicts that define our daily online/offline experiences. To further complicate matters, if bimbofication has been adopted as a sub-culture, it has almost as quickly been adopted into the mainstream. We need think only of the sudden public hunger for Jennifer Coolidge, the Hollywood actor who has transitioned from light, teen movies to the critically acclaimed satire dramedy The White Lotus, while playing ostensibly very similar characters—a fact that demonstrates a newfound public sensitivity towards the bimbo. For all of the garishness of Todorov’s images, her work also includes pockets of genuine aesthetic appeal that speak to the flipside of consumerism: that is, consumerism as comfort and desire. The installation Hollywood is that Way (2021) is comprised of a replica Balenciaga hourglass bag, perched upon a transparent half sphere filled with gel medical capsules. This unlikely combination of items results in a surprisingly beautiful assemblage. Putting aside, for a moment, the cultural connotations of the bag and pills (greed, illness), the form produced Hollywood is that Way is genuinely pleasing to the eye and momentarily suspends any lefty pessimism towards “the state of the world”. Todorov tells me she tries not to take a position on the themes she explores—they cannot be neatly packaged into a good/bad binary, nor can our presence within the digital/consumer landscape be viewed along an inside/outside bind. It is not that each of Todorov’s works tales a neutral; position but, rather, as a collection they create a tug of war that is never resolved.

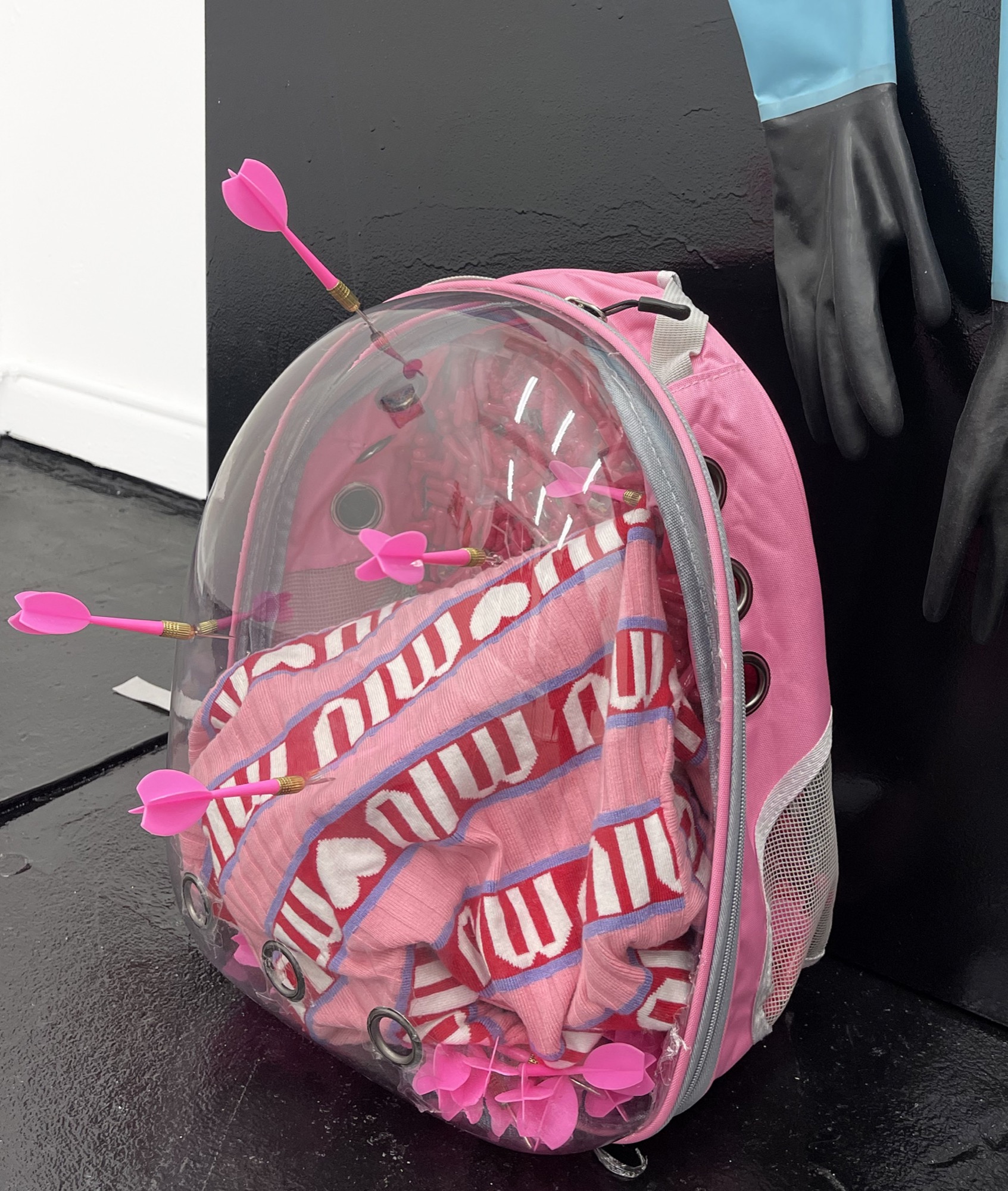

Up until now I’ve been kind of skirting around how to position authenticity in relationship to Todorov’s work. The truth is, I don’t know exactly how to describe it apart from this constant to and fro. I think this is the strength of her work. In her artist statement included in the exhibition’s press release, Todorov writes “purity of self expression has never been ‘authentic’ only perceived as such”. But I don’t think Todorov thinks that there is no such thing as self-expression or that people are inauthentic per se, but instead that the old benchmarks of what authenticity is—characteristics unique to an individual—are outdated. We remain breathing, sentient humans despite our online presence. As Todorov has noted, even if her paintings are outsourced to a workshop in China, they are still made by a human hand. Any dystopian image of a robot-infested post-internet landscape is dispelled by Todorov and replaced by more complex, difficult-to-navigate images (plural) of self and other. In this exhibition, Barbii Production Line (01) (2021) represents the height of this kind of self-performance through artifice. The assemblage is comprised of a transparent, pink backpack (the kind used for transporting cats) filled with an unidentifiable Miu Miu garment and pink arrows. Todorov created the work as an imagined prop for an avatar named Barbii, who she created with IMVU, an online metaverse with its own currency and economy where people interact via avatars—a mimesis of the real world. In bringing Barbii’s props into physical existence, Todorov gives them a material form. Does this make them any more authentic than if they were online? It’s hard to say.

Let’s return to my original contention—that is, that Todorov’s practice is the site of an unresolved dialogue between satire and authenticity. The topography created by the works—at once humorous, garish, appealing and repulsive—operates mimetically in relationship to the contemporary individual’s position within the internet and consumerist stratosphere. The minutiae of daily existence, mediated by the online, has been distilled to what Hal Foster calls “mimetic exacerbation”—a mimesis of mimesis. If images projected by the internet are mimetic of our human desires, then Todorov’s re-inscription of those images into a material form presents a simultaneously satirical and sincere distillation of the end point of these aspirations.

Amelia Winata is a Narrm/Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.