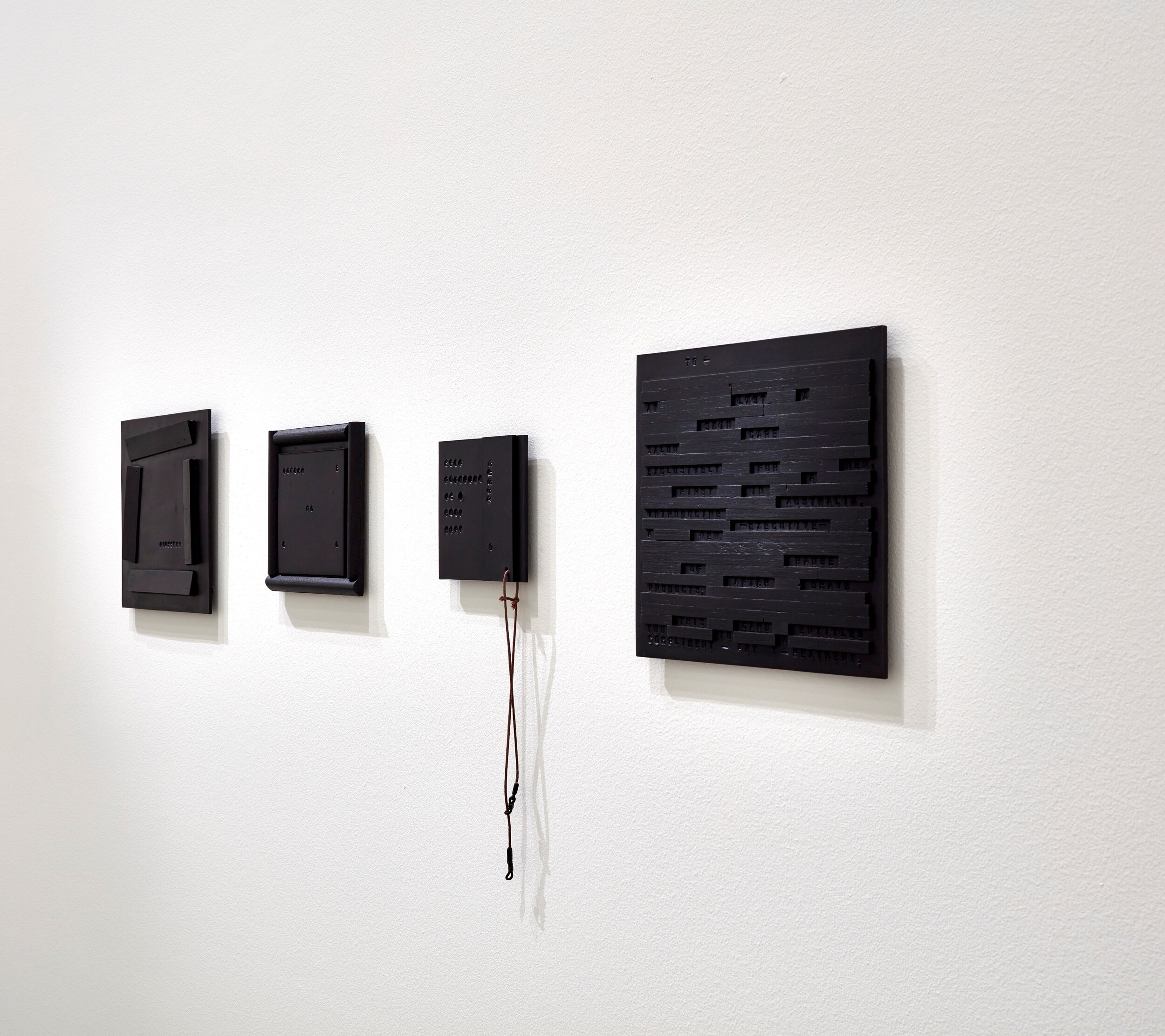

Installation view of the Mitch Cairns, Restless Legs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales 2025. Photo: Mim Stirling. Courtesy the artist, Art Gallery of New South Wales and The Commercial, Sydney.

Restless Legs

Emma O'Neill

There is an upended six-metre power pole in the middle of the room. There, you can sit and view the artworks from a distance. Still, there is a compulsion to stand up; move in close; to lean into the detail of each work; shuffle backwards to gauge their collective effect. Curated by Nick Yelverton, Restless Legs is titled after the condition that prevents one from keeping still, from absorbing one thing at a time. It interferes with the evenings that artist Mitch Cairns sets aside to focus on the page.

Though distraction is at odds with the sustained focus required for reading, there is a certain pleasure in yielding to it. In giving in to the memories stirred by a phrase, lingering on a single vowel, or letting the eyes slip off the page to stare, vacant, at the things out the window. Cairns harnesses such moments across a suite of eight new paintings and nine text-based bronze plates, transmuting lapses of attention into uncanny compositions. Across the exhibition, text and image bring the intimate confines of an evening read and the artist’s everyday surroundings together with the thoughts and memories that preoccupy him.

Installation view of the Mitch Cairns, Restless Legs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales 2025. Photo: Mim Stirling. Courtesy the artist, Art Gallery of New South Wales and The Commercial, Sydney.

Rendered in muted purples, blues, and pinks, punctuated with occasional flashes of red, each painting is neatly structured in broad, linear bands of colour. This underlying geometry gives way to the soft curves and precise swirls of shadow that appear to crease each painted surface. The paintings, executed in two distinct portrait formats—one considerably larger than the other—are arranged in pairs or trios and spaced generously across the wall in honeyed wood frames. Interspersed between them, far smaller black brass plates, rectangular in form and varied in size, punctuate the arrangement. Clouds populate most paintings, their forms resembling the soft collapse of sheets cast onto an unmade bed.

The stems of two bulbous, blush-pink flowers wrap around one another in Self-portrait as a pair of bookends (2024). The title, referencing the familiar genres of portraiture and still-life, immediately poses a series of questions. You puzzle over how one might wedge a few books in between the flowers. How the artist sees himself in them. Then, if you were in a room for reading, what might you be? A bookmark? That’s claimed with “SELF PORTRAIT AS A BOOKMARK” inscribed in text on one of the black brass plates. On another engraving, the artist imagines coming back “AS A DOORSTOP” and “A TRAPDOOR”. A painting of two chimney stacks is titled Self-portrait as a pair of restless legs. Makes sense. At this moment perhaps you, the viewer, are a pair of reading glasses.

Mitch Cairns, Streamlet, 2024, oil on linen, 79 x 68.5cm, the Art Gallery of NSW. Courtesy of the artist and The Commercial, Sydney. Photo: The Commercial.

Along with the floral, Cairns cites Italo Calvino’s 1963 collection of short stories, Marcovaldo, through the inclusion of sky, water, vegetation and the sculptural remnant of a tree (power pole). Calvino’s stories follow the title character as he seeks out nature amid the concrete sprawl of a nameless city. In the story “Where the River Is Bluest,” Marcovaldo travels beyond the realms of the city to look for uncontaminated food—only to fish from a stream turned brilliantly blue by the runoff from a paint factory. In Streamlet, Cairns paints his own babbling stream in blue, its path cutting diagonally across the canvas, threading neatly over and under the wooden slats of something domestic. A bookshelf? No. It’s the underside of a bedframe, I decide, water and paint secretly coursing beneath Calvino’s reader.

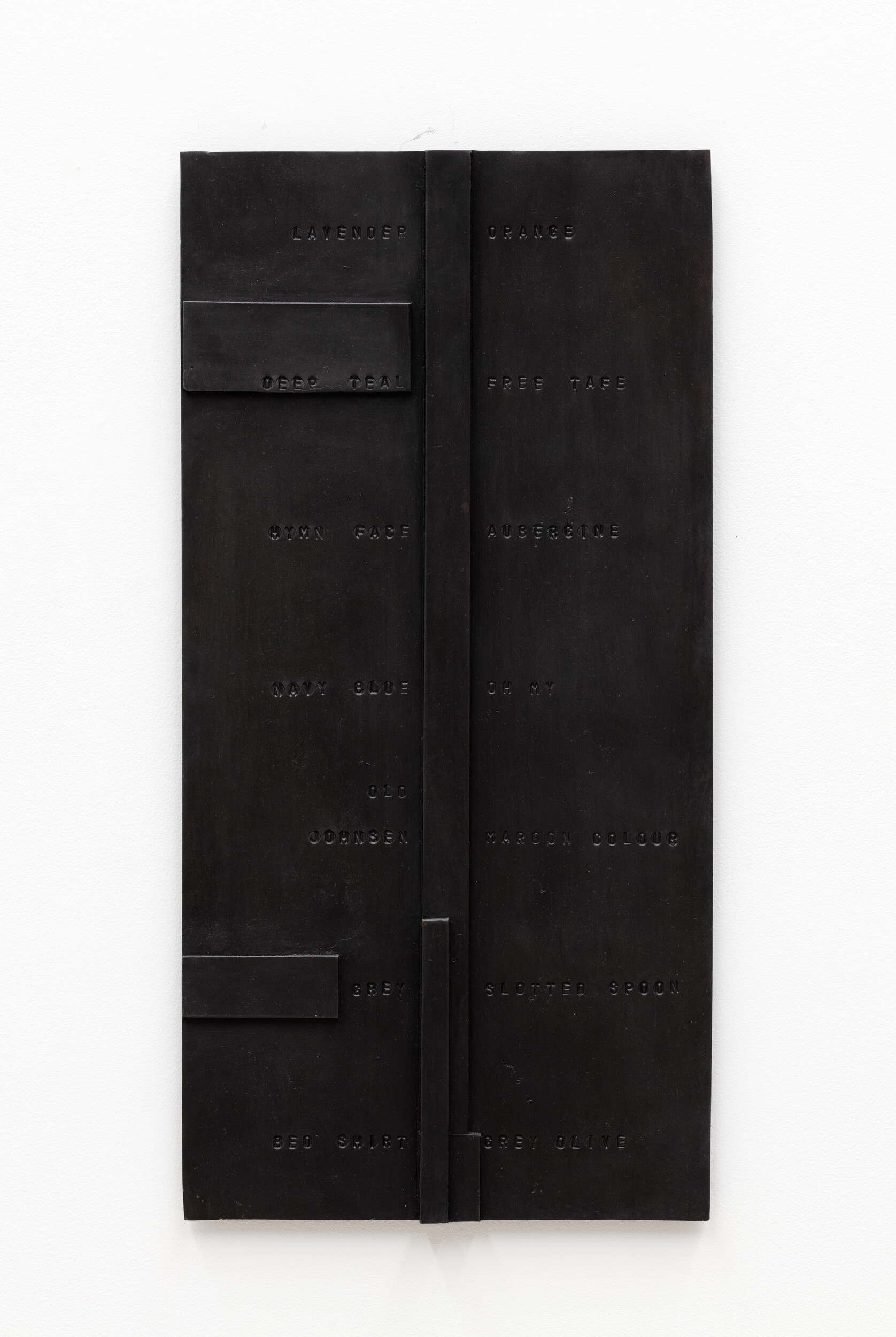

Mitch Cairns, Swatch plate, 2024, bronze, 60 x 30 cm, the Art Gallery of NSW. Courtesy of the artist and The Commercial, Sydney. Photo: The Commercial.

Amid an orderly procession of variously sized black brass plates, Swatch Plate (2024) bears colours typographically inscribed and listed vertically across two columns: “TEAL BLUE,” “LAVENDER,” “AUBERGINE,” “NAVY BLUE,” and so on. Also, “FREE TAFE.” Not a hue I’d encountered—but a Labor election promise inscribed in time. If it were a colour, maybe it would be the creamy yellow of Life-Like’s painted bedside lamp or even the pastel-pink skyline of CPT (after John Bloomfield) (2024). The list is like an index of the colours in the canvases. You search for them in the paintings, flipping back and forth.

In his use of titles and text, Cairns smuggles both politics and play. Language offers “a method of sidestepping imagery… to get to the thing you were thinking about the entire time,” he once told artist Michael Snape, recalling the 2015 work FINCHES, an enormous painting of the wrong bird (a seagull). The works across Restless Legs emerge as tender riddles, leaning toward fragmentation over clear registration, making slippery the friction between the immediacy of the image and the pull of words.

Mitch Cairns, ERATO, 2024, oil on linen, 124.5 x 104.5cm, the Art Gallery of NSW. Courtesy of the artist and The Commercial, Sydney. Photo: The Commercial.

Tricks of vision continue. ERATO (2024), named for the Greek muse of lyric poetry and her symbolic lyre, depicts a manicured hand plucking at a harp. With harp and hand rendered equal in size, either the instrument appears unusually small or its player is improbably large, inviting a recalibration of perception. For the stout drinker, the harp invokes the Guinness logo. This connection is affirmed by the provocations in brass on Declarative plate (2024), where the artist references Arthur Guinness’s landmark brewery with the phrase: “CAME BACK BREWED AT ST JAMES GATE.” Other famous people are in the room too, albeit less subtly referenced. “ROUSSEAUN” appears on the Rousseau plate (2024), and Frederick McCubbin’s name is printed in a recreated 1889 work didactic entitled Presentation plate (2025).

The latter work gestures obliquely to Cairns’s 9 –5 (2024), hung nearby. Here, the title numbers appear on a slant, assembled with geometric shapes and flanked by extinguished candles and an oversized cigarette. One of the founding figures of the Heidelberg School, Frederick McCubbin, helped stage the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition in Melbourne in 1889—a show of rapid impressions of bush and city life painted on cigar-box lids. Cairns’s works overlap in subject matter, but with his precise line and angular forms, operate on an entirely different visual register.

Installation view of the Mitch Cairns, Restless Legs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales 2025. Photo: Mim Stirling. Courtesy the artist, Art Gallery of New South Wales and The Commercial, Sydney.

These brass plates really function as footnotes, encoded with the artist’s poetic free association. Face of Man plate (2024) is a gift certificate to his late grandmother’s skincare salon for men in The Strand arcade, the first of its kind in the country. The appearance of the 9-to-5 adage stems from Cairns’s reflection on her orderly daily rhythms, a far cry from his own.

Further intimate references surface. Place marker plate (for Roland) (2024)—a “SELF PORTRAIT AS BOOKMARK”—is not for Barthes, but Cairns’s son. So, too, is the depiction of Centre Point Towers a nod to a painting of Redfern’s TNT towers by John Bloomfield, Cairns’s National Art School (NAS) teacher. These personal connections are unsurprising from an artist who was awarded the 2017 Archibald Prize with a portrait of his partner, Agatha. Indeed, Bloomfield was stripped of his Archibald title in 1975 for “painting from a photograph.” His reappearance 50 years later coincides with this year’s iteration of the portraiture prize taking place upstairs.

It’s fun in here, trying to crack Cairns’s codes. At once lively, disarmingly intimate, and pleasingly allusive, these paintings and plates capture the quality of a wandering mind while creating a restlessness in our own processes of interpretation. Shuttling between image and text, Restless Legs resists an easy read. Still, it’s all quite pleasurable to look at. Even if you get distracted.

Restless Legs was originally scheduled to run until June but was closed early “due to unfortunate, unforeseen circumstances” according to the AGNSW. It will travel to Wollongong Art Gallery in September 2025.

Emma O’Neill is an arts manager, writer and curator based on unceded Gadigal land.