Robert Campbell Jnr, Death in Custody, 1987, acrylic on canvas, 81 x 120 cm. Janet Holmes à Court Collection, Perth © Estate of Robert Campbell Jnr, licensed by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.

Blak In-Justice Incarceration and Resilience

Lisa Slade

During a tour of Fremantle Prison about a decade ago, I asked the warden-cum-tour guide about the art on the walls of the gaol. “What art?” he replied. “This isn’t art; it’s the work of criminals.” His demeanour, and relevant work experience, cautioned me against talking back, but Heide has done just that in their current exhibition Blak In-Justice: Incarceration and Resilience. The exhibition is curated by Kent Morris, Barkindji artist and Creative Director and Founder of The Torch program, in which First Nations prisoners in Victorian gaols are supported to make art on the inside and supported, once released, to continue the journey from “criminal” to artist. Blak In-Justice talks back, and blak, to the criminal legal system where First Nations Australians are the most incarcerated people on the planet. It also talks back to that Freo prison guard, firmly positioning those incarcerated, then and now, as artists.

At the entry to the museum, a supersized marble tablet carries the number 551, etched in blood-red serif Roman numerals. Titled Remember Me, this 2023 sculpture by Kamilaroi artist Reko Rennie calls us to remember the 551 people who have died in custody. There have been a further forty-two deaths since the making of the work. As I write, a young Warlpiri man has been killed by police in a supermarket in Alice Springs. It is Reconciliation Week. By the time this article is published, another Aboriginal man will have died while in police custody at the Royal Darwin Hospital.

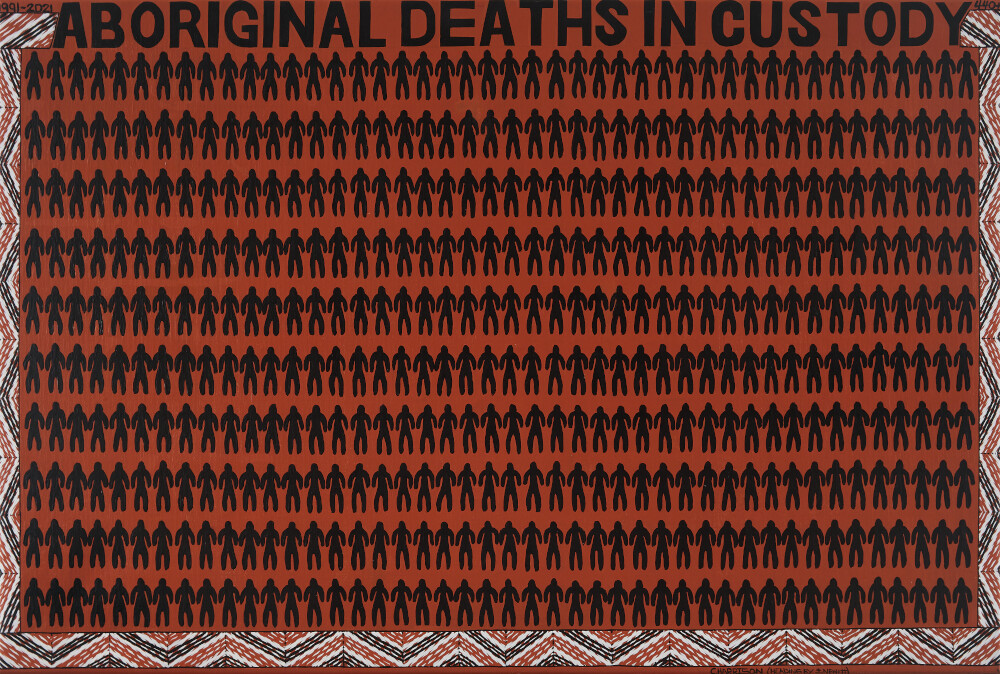

C. Harrison, Deaths in Custody, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 59 x 87 cm. Private collection New South Wales, Courtesy of the artist and The Torch. Photo: Mick Bell

How can art deal with this heavy toll? In Death in Custody from 1987, Ngaku artist of the Dunghutti nation Robert Campbell Jnr chronicles the all-too-familiar pattern of Aboriginal incarceration—from minor offence to death in a prison cell—across just four frames rendered in the artist’s now-signature X-ray pop style. Nearby, Torch participant C. Harrison’s Deaths in Custody (2021) represents each death as a human figure in a grim tally that reminds us of the double meaning of “killing time” inside. (The use of the anonymising “C” suggests the artist remains incarcerated.)

Harrison’s work is displayed in the first long gallery on walls of institutional navy blue, in the company of works by high-profile Australian artists, including Vernon Ah Kee, Richard Bell, Gordon Bennett, Destiny Deacon, Karla Dickens, Trevor Nicholls, and Judy Watson, among others. Herein lies the curatorial crux of the exhibition, and arguably its greatest opportunity and challenge—to position the canonical alongside the work of former and current inmates and Torch participants, including Thelma Beeton, Melissa Bell, Stacey Edwards, Sean Miller, and Robby Wirramanda. Here they are seen as artists, not offenders, as Melissa Bell recounts in her own words on the gallery wall and in the accompanying publication: “I don’t get recognised for being in prison; I get recognised as an Aboriginal artist.”

Sean Miller, Sunset, 2021, earthenware, 8.8 x 25.1 x 24.6 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Naarm/Melbourne. Purchased through NGV Supporters of Indigenous Arts.

Melissa Bell’s painting The Murray River (2024) points to the power of The Torch program as a cultural connector and signals art’s role in rehabilitation. Exhibited in the second large gallery on desert-red walls alongside the work of other Torch artists, including Felicity Chafer-Smith, Bell’s painting, with its snaking rivers of colour, chimes with works by Walmajarri artist Jimmy Pike. Painter, printmaker, fashion designer, and all-round storyteller, Pike developed his distinctive voice while in Fremantle Prison in the early 1980s. This was Pike’s second time in Freo gaol, underscoring the recidivism to which First Nations people are subjected, with more than fifty per cent of those who have served sentences ending up back inside. Pike’s voice is one of the loudest in the exhibition, proliferating his visionary desert psychedelia, now a Walmajarri trademark evident in the work of contemporary artists like John Prince Siddon and others working with Mangkaja Arts at Fitzroy Crossing. The inclusion of more than a dozen works by Pike, notwithstanding my enthusiasm for his work, is to the detriment of other voices in the exhibition. Works by several artists in the first long gallery, including those by Vernon Ah Kee, Julie Dowling, Trevor Nickolls, and Reko Rennie, could have benefited from more space. Moreover, the oversized and overdesigned wall texts demanded attention that could have been better devoted to key works by some of the established artists who spoke to the experience of The Torch artists.

Installation view of Blak In-Justice, Heide Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Christian Capurro

The inclusion of garments from fashion label Desert Designs in the adjacent room positions Pike as a progenitor for what is now a burgeoning First Nations textile and fashion movement. In the 1980s, Pike licensed his artworks to Desert Designs owners Stephen Culley and David Wroth, who formed a relationship with him through art classes at Fremantle Prison. The placement of the garments near two watercolours by Australia’s most celebrated incarcerated artist, Albert Namatjira, creates a jarring juxtaposition. Perhaps this positioning of the brightly coloured printed clothes—worn on the “outside” by the predominantly white middle class who have never stepped “inside” a prison—is the conscious clang of the exhibition’s ironic message: that white Australia has often defined itself through the creative efforts of the dispossessed and incarcerated.

It would be a diversion, but a nonetheless compelling one, to list the names of the once-incarcerated artists included as major players in the exhibition 65,000 Years: A Short History of Australian Art at the Potter Museum of Art at the University of Melbourne. The history of Australian art is intertwined with the story of Indigenous incarceration, or, as Aboriginal writer Tristen Harwood writes in his catalogue essay for Blak In-Justice, “art made in prison is critical to our understanding of any notion of art on this continent.” Many of the artists represented in the more than four hundred works currently at the Potter Museum have had, to loosely paraphrase Ngarrindjeri artist Nickolls, a brush with the law. As the grim numbers reveal, an Aboriginal person is more likely to go to gaol than to university.

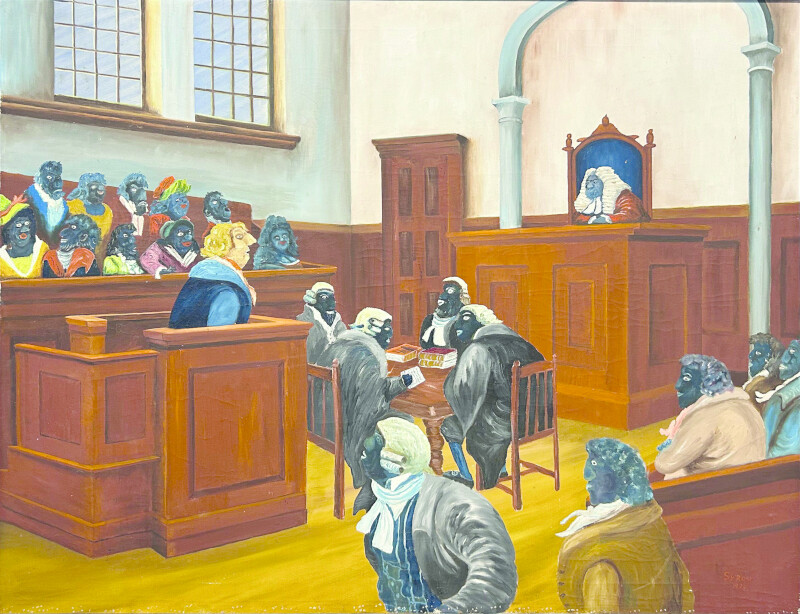

Gordon Syron, Judgement by His Peers, 1978, oil on canvas, 102 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Newstead Art, Dharawal Country/Sydney.

The predilection for colour—and lots of it—and the use of shaped or clearly delineated wall sections is another point of connection between Blak In-Justice and 65,000 Years, suggesting the rise of the overzealous exhibition designer. These display tactics punish some works more than others, as is evident in the small, red-ochred room showcasing Namatjira’s watercolours, Pike’s psychedelic graphics, and the black-and-white prints by Wiradjuri artist Kevin Gilbert. There is a strong case for Gilbert’s works to be reunited with works by other historic elders in the exhibition, such as Gordon Syron’s Judgement by His Peers (1978). In his visceral figurative painting, the all-white jury that judged Syron as a Black man is flipped to reveal systemic hypocrisy and racism.

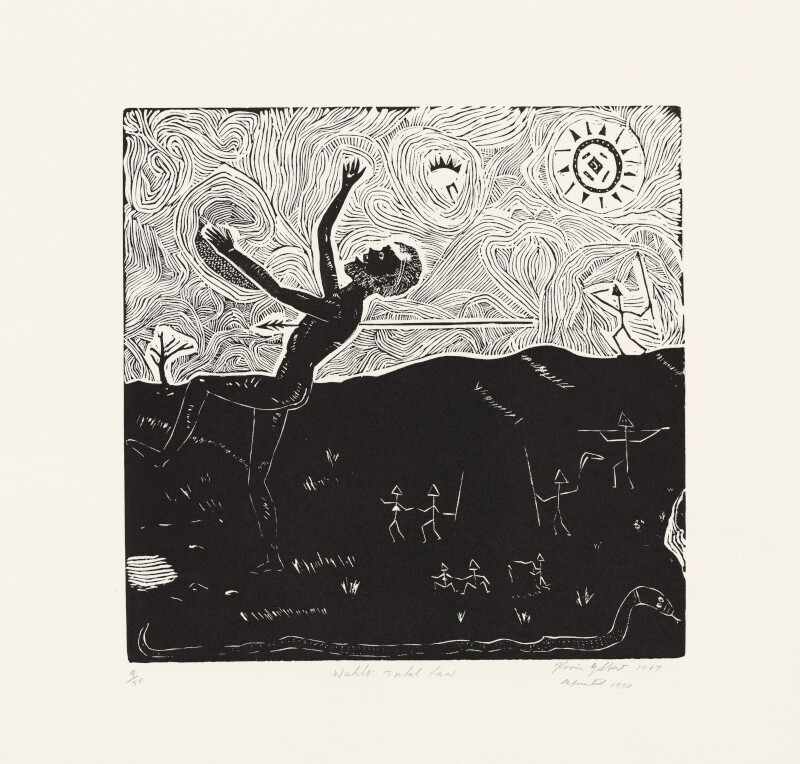

Like Pike, Gilbert was a polymath, and in his 1967 linocuts on loan from the National Gallery of Australia, the artist, playwright, poet, and activist converge. Gilbert’s influence cannot be overstated; his works representing Aboriginal justice, such as Wahlo: Total Law, were made on salvaged linoleum using improvised tools and smuggled from prison. Gilbert’s mark-making not only ignited a First Nations political printmaking movement but also reinvented Aboriginal carving traditions, particularly those from the south-east.

Gilbert’s fine, rhythmic, linear approach is echoed in the ceramic works by Gamilaroi artist Sean Miller, which are displayed at the opposite end of the gallery. Described in the exhibition publication by Harwood as a “devotional iteration of Country,” Miller’s first works in clay were made while working with The Torch’s Kent Morris in Loddon Prison in Castlemaine. While clay is Country, best articulated by Uncle Jack Charles when he says, “clay is land, land is where we belong,” Miller’s incised mark-making connects him with a “lineage” of artists, including Brook Garru Andrew and Reko Rennie, for whom the line and the chevron signify strength and connection.

Kevin Gilbert, Wahlo: Total Law, 1967/1990, linocut, ed. 9/50, 35.3 x 35.4 cm. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Gordon Darling Print Fund 1990.

Installation view of Blak In-Justice, Heide Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Christian Capurro

One of the most potent curatorial dialogues in Blak In-Justice unfolds between the 2017 NATSIAA award-winning installation Kulata Tjuta—Wati kulunypa tjukurpa (Many Spears—Young Fella Story), an intergenerational collaboration by Anangu elder Frank Young, his niece Unrupa Rhonda Dick, and grandson Anwar Young, and Tony Albert’s Brothers (The Prodigal Son) series from 2020. Both works are monumental in intent: a young “wati” behind suspended spears and a trinity of brothers hallowed in glass. This is an architecture of loss and of defiance. As Frank Young decries, “we need young people to be standing behind their culture not behind bars.” A recent work by Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens depicting kids wearing balaclavas, titled Criminalising Babies (2025), is positioned near the gallery entry, as though to presage this curatorial theme. Dickens suggests resistance with her embroidered ceremonial adornments incorporating seeds, string, and feathers as markers of cultural strength.

Karla Dickens, Criminalising Babies, 2025, UV print on aluminium, 110 x 114 cm. Courtesy of the Artist.

The exhibition’s subnarrative of the prison as a wellspring of cultural and political resistance is personified in the figure of Aboriginal painter Ronald Bull. A reproduction of his F Division, Pentridge Prison mural, now “imprisoned” under protective cladding, is adjacent to the exhibition entry and serves as backdrop for his modest, yet potent, untitled and undated landscape held in the collection of the Koorie Heritage Trust. Hailed as the next Albert Namatjira, Bull spent a lifetime forced from one colonial carceral context to another, but this failed to quell his influence or his resistance. Through Bull’s story, and reiterated in Syron’s work, we are alerted to the fact that the real recidivists are the system makers—the lawmakers, not the lawbreakers. In other words, it is our legal and so-called justice system that reverts time and again to criminal behaviour.

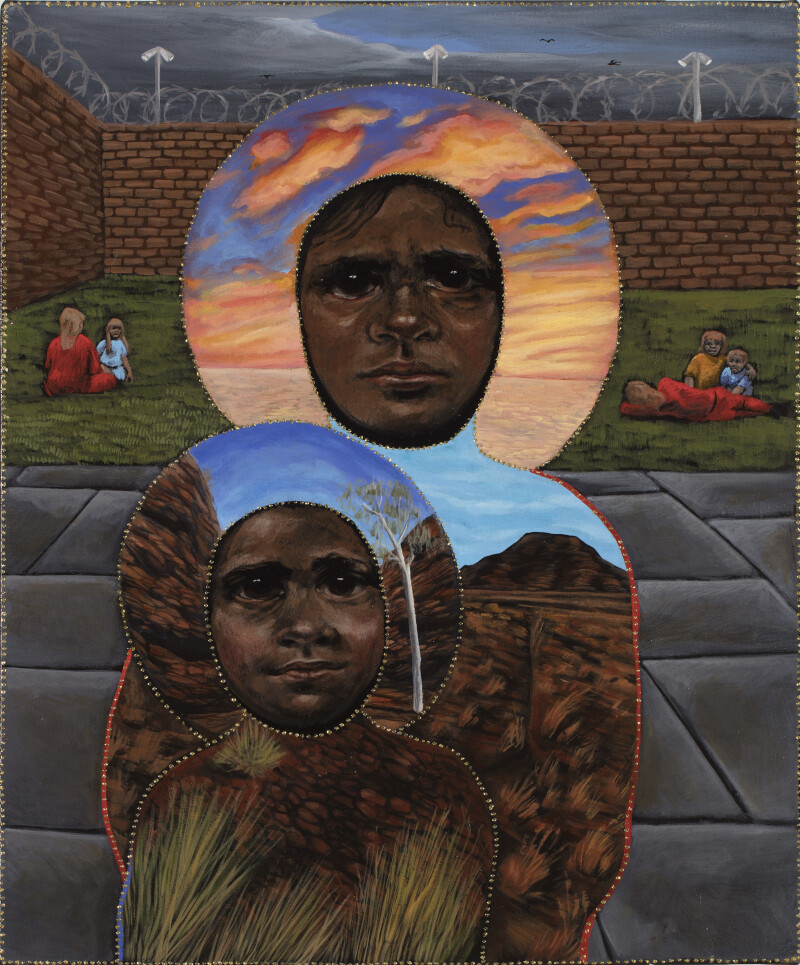

Julie Dowling, The Visit, 2002, synthetic polymer paint, red ochre, glitter and metallic paint on canvas, 59.8 x 50 cm. the State Art Collection, Art Gallery

Heide Museum of Modern Art may, for many, be a surprising home for this exhibition, but the site’s socially engaged coterie of modernists, their energies still present in the weatherboard farmhouse, invite conversations about class, history, and, most importantly the role that art and artists have to play in shaping social change. I left Bulleen with one work front of mind, and heart: Yamatji artist Julie Dowling’s The Visit (2002). On loan from the Art Gallery of Western Australia, The Visit is made with red ochre, glitter, acrylic, and metallic paint. Dowling depicts an imprisoned mother and visiting child, who embody both incarceration and resilience. With their bodies and halo auras painted in hues and scenes that recall both Namatjira and Bull, they are, most importantly, Country.

Professor Lisa Slade is the Hugh Ramsay Chair in Australian Art History in the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne. Between 2015 and 2024 she was Assistant Director, Artistic Programs at the Art Gallery of South Australia. Her curatorial projects include Vincent Namatjira: Australia in ‘Colour and Sappers & Shrapnel.’