Loading Dock, the former LM Ericsson Factory, Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung, Gunung-Willam-Balluk Country. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

Makiko Ryujin’s Studio Workshop in the Former LM Ericsson Factory

Alex Brown

The tips of Makiko Ryujin’s fingers were still stained faintly with indigo dye as she stood in the gallery talking to friends, while Ephemeral Blue loomed like a planetary body over her shoulder. Installed in the Main Gallery at Craft Victoria as part of In the Making alongside the work of Emma Davies, Noriko Nakamura and Michaela Pegum, Ryujin’s sphere comprises 156 thin, vertically hung strips of burnt and dyed radiata pine.

It seems hardly worth saying that, before it was a crafted object on display, Ephemeral Blue was brought into being—as an idea, a suite of materials, a set of tests and prototypes—somewhere else entirely. The nature of these spaces of becoming isn’t typically made visible within exhibition environments. Like the dye on Makiko’s fingers, traces of process may linger, but we can’t easily encounter the site conditions, constraints, and spatial configurations that contain or sit beneath the work in the making, even in a craft and design exhibition that foregrounds process and materials.

In Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, Tim Ingold suggests that “even if the maker has a form in mind, it is not this form that creates the work. It is the engagement with materials. And it is therefore to this engagement that we must attend if we are to understand how things are made.” In this sense, and without claiming causation or reanimating the corpse of architectural determinism, this architectural review returns to the studio workshop as the site of material engagement, hoping to unfold a broader set of loose correlations, ripples, and resonances between work and workspace.

Entrance to the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

From Craft’s inner city gallery space, it’s a 45-minute drive to Makiko’s studio inside the former LM Ericsson factory complex at Broadmeadows. Opened in 1963 to manufacture components for the crossbar switching system that was being introduced in Australia’s telephone network, the factory remained open until 2007. The complex was constructed on an 18-acre site on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people, including members of the Gunung-Willam-Balluk clan, and includes a five-story office block to the property’s northern edge and two sprawling factory and storage facilities.

The former office building is currently a Hume City Council Hub, while the production facilities now contain colleges, small businesses, not-for-profit organisations, and a series of studios for artists and designers. When Makiko meets me at the loading dock, we walk inside and set off down a long corridor, occasionally stopping to say hello to industrial designers and painters working behind a series of non-descript doors. Her studio workshop is on the lower ground floor, which can be accessed by a large stair and lift in the middle of the building, eventually emerging at street level as the site falls away to the north-east.

Canteen in the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

This part of the building was initially used for staff access and amenities. Partway along the lower ground corridor, Makiko flips a switch at the side of a dark box on the wall. A light flickers on to reveal a backlit Ericsson Australia directory map. The “You are here” callout marker tells us that we are at the edge of the cafeteria, between the travel office and credit union, not far from the social club and gymnasium.

Makiko Ryujin’s studio workshop in the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

Another set of plain white doors in the corridor takes us into Makiko’s space: a collection of rooms of various sizes with a low ceiling and no direct access to natural light or ventilation. As disorienting as the maze-like corridors on the way to the studio have been, this space serves as a reminder that we are deep within the plan of the lowest part of the building.

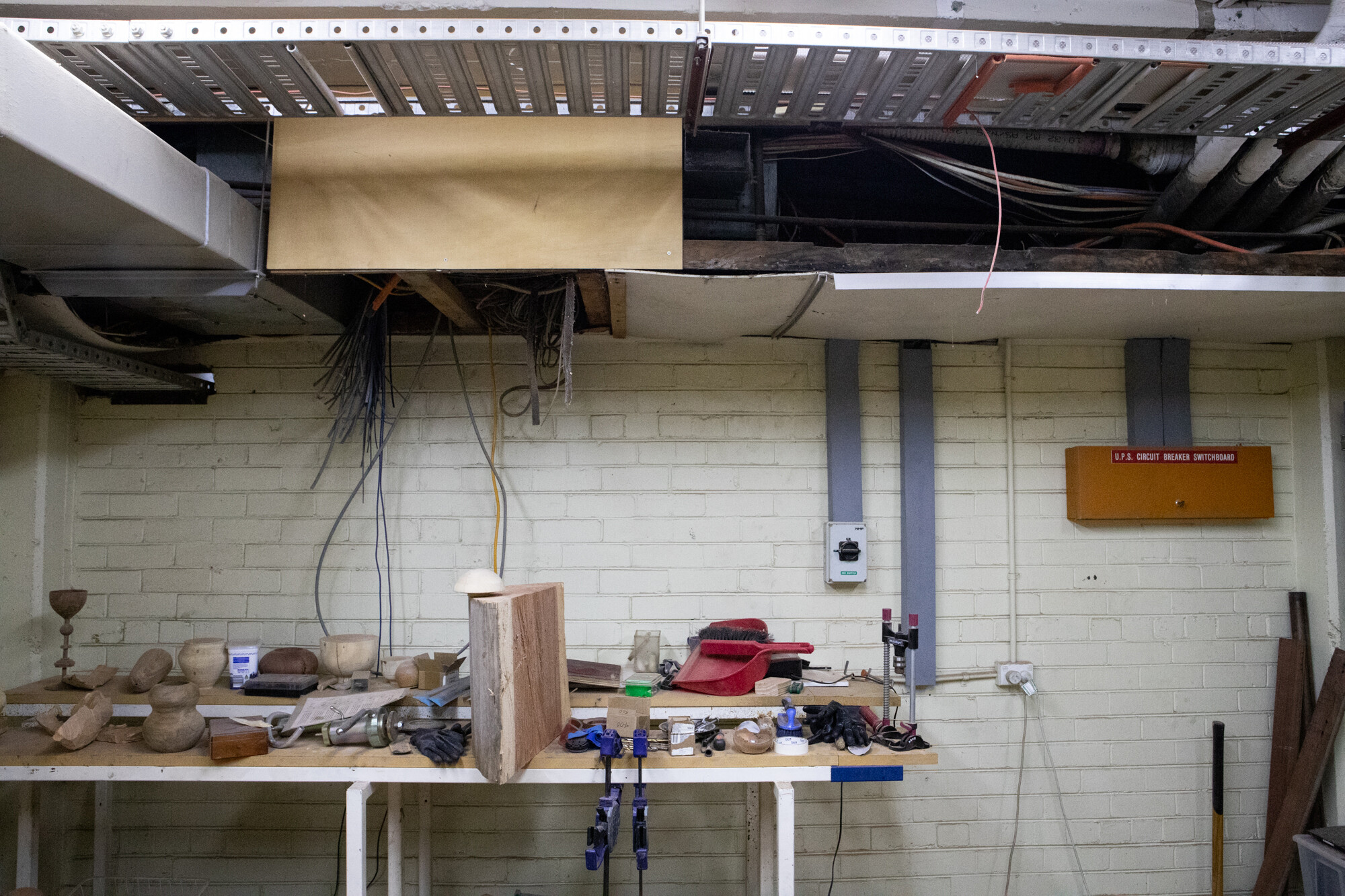

Makiko Ryujin’s studio workshop in the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

Makiko has been here for a couple of years. She’s not sure if she started thinking more about the sky when she moved in, but she’s acutely aware that it is both absent from the studio space and central to the development of Ephemeral Blue, which recalls the expansive gradient of the fading sky viewed from above the clouds during flight. The work is the first of her pieces to use blue and to engage with traditional Japanese indigo dyeing processes.

Ephemeral Blue in the making in Makiko Ryujin’s studio workshop in the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

Unlike Makiko’s previous studios, this is a relatively large space, and it’s not shared with other artists and makers. Her practice, and its careful engagement with timber across various states, has always demanded space and time to let things season and weather. Here in the former factory, however, each area or room hosts particular sets of works, materials, and equipment. Processes can exist concurrently, and material rarely needs to be packed away or relocated prematurely. Ephemeral Blue seems to have taken full advantage of these conditions, both in terms of the testing and prototyping of the work’s ambitious support structure and hanging elements, as well as the preparation and maintenance of the microbial fermentation process for making indigo dye, which occurs over weeks. Low drop ceiling tiles concealed a range of possible fixing points in the slab to support the work as it took shape, part of a series of thin skins across the interior that have been progressively layered onto the building’s heavy concrete and masonry structure. None of the spans are particularly large down here, but the industrial scale of the concrete structure is still apparent. The lightweight partitions and dividing walls that define the studio have little regard for the rhythm of this broader structural logic, however, creating a range of offset volumes that leave space for larger projects in wider pockets of the studio.

Makiko Ryujin’s studio workshop in the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

Like the complex as a whole, the studio retains elements of the building’s industrial history—ones that suggest that the staff amenity level took on its own production role as the manufacturing processes and technologies changed across the second half of the twentieth century. Cable trays snake through the space, with bundles of wiring occasionally bursting from risers and bulkheads. At the back of the woodworking room, an eye washing station suggests the one-time presence of chemicals, vapours or debris. With the size of the space and the presence of these abandoned infrastructures, something of the old factory floor seems to resonate in the use of the studio workshop and Makiko’s practice. The repeating components and structural system of Ephemeral Blue set up a production line, a soft factory logic that moves between the studio workshop and building edge to fabricate, burn, dye, and assemble the work.

Ephemeral Blue disassembled, Makiko Ryujin’s studio workshop in the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

On the way back out, we drop into Ryan Hoffmann’s studio on the building’s main level, which has a high ceiling and some small, translucent skylights. The light is more conducive to painting up here, but the space retains an intense interiority. Makiko and Ryan both talk about the way this place separates its occupants from the world outside and each other. It’s not simply a matter of scale or circulation, nor is it a completely unwelcome condition. For better or worse, they both agree that the old factory pulls the work into unrelenting focus. These spaces were originally designed for approximately 3,000 employees of a single company, for the activities of its various departments and divisions. What was previously a small city in the suburb is now the framework for a series of smaller individual and collective sites of making without areas designed for incidental interaction and exchange.

Ground floor of the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

Everyone in the complex seems to understand that the building is hiding in plain sight, a condition that is always temporary and will inevitably follow a familiar pattern. A studio workshop like Makiko’s space can only exist in this in-between state—during the aftermath of the building’s intended use, in the years before the next wave of development wipes it all away.

Ground floor of the former LM Ericsson Factory. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

In the process of fading from view, the Broadmeadows LM Ericsson factory is, for the moment, being lightly reconfigured to host and support new processes of making and artistic practice. Within this expanded story of process and making, the architectural qualities and historical fragments of its spaces sit beside and underneath Makiko’s practice—not in any neat or obvious way, but rather as rough, uneven thoughts and loose associations.

Installation view of Makiko Ryujin’s work Ephemeral Blue (2025), on display at Craft Victoria in the exhibition In the Making, 2025. Photograph by Claire Armstrong.

My gaze returns to the suspended, splintering, not-quite mass of Ephemeral Blue and its endless remaking and breaking apart. The piece belongs here in the gallery alongside Noriko Nakamura’s hand-carved limestone pieces, the shimmering twine fabrics of Emma Davies and Michaela Pegum’s electroformed copper and silver organza petals. Nevertheless, I think it might also belong in the lower ground floor of the former LM Ericsson factory. Although there’s no easy or straightforward connection here, Makiko and Ephemeral Blue have been part of the reshaping of this building and its architectural afterlife. This reshaping and its related processes of “material engagement” (to paraphrase Ingold) potentially also leave faint traces on Makiko’s artistic practice.

Makiko Ryujin’s hands in the making of Ephemeral Blue. Photograph by Makiko Ryujin.

Alex Brown is an architect and senior lecturer in the Department of Architecture at Monash Art, Design and Architecture. Her research explores twentieth-century and contemporary art-architecture relationships, architecture exhibitions, and architecture and radicality from the 1960s onwards.