Claudia Nicholson, If The Mountain Is Burning, Let It Burn, 2024. Installation view, UTS Gallery. Courtesy the artist and UTS Gallery. Photo: Jacquie Manning

If The Mountain is Burning, Let It Burn

Jennifer Yang

When the literary theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick encountered a photograph of the American textile artist Judith Scott hugging her sculpture, the image compelled her to assemble her writings into the monograph Touching Feeling (2002). Drawn to the “closeness” the photo established between Scott’s body and the fibrous, organic form of her sculpture, Sedgwick observed that “the sense of sight is seen to dissolve in favour of that of touch.” Sedgwick was witnessing a “transaction of texture”—a moment of embrace, between a woman and her creation, and between the colliding sensualities of the optic and haptic. And from this transaction arose an ineffable affective richness (was it sorrow, triumph, love, or relief?), capable of extending outward and touching the viewer. That is, the photograph offered something in excess of the visual.

Such photographic synaesthesia flows through Claudia Nicholson’s If the Mountain is Burning, Let it Burn. The outcome of a year-long residency facilitated by the UTS Gallery, the exhibition marks the artist’s first official exercise in photography. Nicholson has not sought to demonstrate mastery over the medium. With little interest for conventional standards of technical excellence—sharpness, resolution, chemical perfection, and so on—Nicholson presents prints liberated from the constraints of discipline. For If the Mountain is Burning, Let it Burn, the artist has sieved through a personal archive of images, combining photographs taken by her father in Nicholson’s birthplace of Bogotá, Colombia; prints purchased and found by Nicholson during subsequent visits from Australia to Colombia; and images taken by the artist herself across both countries.

Claudia Nicholson, If The Mountain Is Burning, Let It Burn, 2024. Installation view, UTS Gallery. Courtesy the artist and UTS Gallery. Photo: Jacquie Manning

There is no chronology—no linear logic of travel or homecoming—in the arrangement of the photographs, but Nicholson provides temporal and spatial clues for the viewer. By the entrance to the Gallery, for example, a large triptych bears the title Amnesty of Rojas Pinilla 1953 #1 (2024). The title references the moment in 1953 when the Colombian military colonel Gustavo Rojas Pinilla staged a coup against the country’s extreme right-wing government, ascending to power during an extended period of civil war and insurgency that has come to be known as la Violencia (the Violence). In the absence of statistical counts and official records, la Violencia and its excesses have remained largely unquantified and without causal explanation. Thus, when formulating a method to interpret this history, the political scientists Cristina Rojas and Daniel Tubb have borrowed from the toolbox of psychoanalytic theory to invent the term tanatomo-power—a welding of the Spanish translation of Thanatos (the Freudian death drive) with the Greek anatomē (meaning dissection, especially of the body). Tanatomo-power, for Rojas and Tubb, describes an exceptional technology of power which operated via the policing and repression of the body and biological imaginaries. La Violencia was sustained by acts of corporeal violence, exacted on unfigured bodies. These bodies exist outside of the frame of history and its photographic traces, and haunt it yet.

Nicholson’s photographs give form to this haunting. Amnesty of Rojas Pinilla 1953 #1 discloses only hazy figures, their faces shadowed by the harsh white light of the sky over the hill. A bead of light has formed on the woman’s nose in the third print, and the skin of her neck and shoulder is blemished with scratches left by light, dust, heat, and time on the emulsion. Nicholson relishes in the indexical quality of analogue film; here the particulates of an atmosphere are registered, preserved, enlarged for viewing; the spectral bodies on whom La Violencia was visited is lent specific matter, form, and shape. Yet, as the title of the triptych suggests, at stake is not the political act of restitution, but rather amnesty or pardon—an act of deliberate forgetting. The photograph is summoned, not as evidence of remembrance, but as an object which might represent all that is absent and lost to time, history, and memory. This is a kind of destruction also.

In the short but lucid catalogue text, art historian Verónica Tello intuits this destructive impulse, pointing first to the exhibition’s title, which twists the lyrics of Afro-Colombian bullerengue song Que Se Quema El Monte (that the mountain is burning) (2006) by the musician Etelvina Maldonado. Evoking both the cataclysmic and the cathartic, Nicholson uses the proposition “if the mountain is burning,” to deliver the imperative to “let it burn.” Tello, drawing a parallel between Nicholson’s Palace of Justice Siege 1987 (2024)—an image taken by Nicholson’s father, 34 years after the coup—and an image from her own archive, of the bombed Presidential Palace in Santiago de Chile in 1973, considers that, perhaps, “destruction is part of our heritage.” Again, a history is traced in Nicholson’s title: in the decade and a half following the defeat of Pinilla’s National Popular Alliance in the 1970 elections and the rise of the 19th of April Movement (M-19), guerilla fighters captured the Supreme Court in 1985. The next day, the Colombian Army led an assault on the building to retake it by force, resulting in the death and disappearance of civilians, hostages, and rebels, and the complete incineration of thousands of legal documents and criminal records. Nicholson’s photograph, however, pictures only the architectural remains of tragedy. The Palace of Justice is the subject, but the image is so magnified that, aside from a fragment of sky, only the bruised concrete blades of the façade are visible. Nicholson brings handwritten inscriptions to the front of the print; overlaid onto the image also is the impression of cellophane tape, the edge of a typescript, and a message in cursive that reads, “thinking of you.” As these elements suggest, it is not Nicholson’s aim to forensically uncover the facts of history. She understands that the photographic archive and all its exclusions can only offer a trace of a lost past. In Jacques Derrida’s formulation of the mal d’archive (archive fever), a tendency toward destruction coexists with the desire for preservation. For Nicholson, destruction yields and yields to resistance—she is, after all, referencing living traditions of song and dance which sustain cultural knowledge, linguistic patterns, and histories of protest in her tribute to Maldonado. Nicholson makes room for a way of seeing and being that must exist in the wake of destruction. There is no preciousness for a perfectly preserved original, and no obsession with a history told through empirical truths. “She destroys it again and again,” writes Tello. A clearing is opened. In bleed other memories.

L-R: Claudia Nicholson, Palace of Justice siege 1985; Santa Marta 2008; Amnesty of Rojas Pinilla 1953 #2, 2024. Archival pigment prints, 81 x 110 cm each. From Claudia Nicholson, If The Mountain Is Burning, Let It Burn, 2024. Installation view, UTS Gallery. Courtesy the artist and UTS Gallery. Photo: Jacquie Manning

They appear in no particular order: in El Totumo 2008 (2024), the contours of a person’s shoulders and collar bone are smoothed by the viscous gloss of soft volcanic mud, and in Rio 2004 (2024), we see a pink-hued image of a riverbank processed from a corroded negative. These pictures visually dialogue with images of artefacts from the Museo del Oro, an archaeology museum of pre-Columbian artefacts in Bogotá, which at once gesture toward and transgress their modes of display. A sterility emanates from Conch, Museo del Oro 2013 (2024), in which a distance is maintained between the lens and the golden conch pictured in its display case, the flash emitted by the camera pooling in the glass. A mask floats like a ghostly form, doubling between Mask, Museo del Oro 1987 (2024) and Mask, Museo del Oro 2018 (2024), the former of the two prints tagged with snippets of text from an artefact label. In Bust, Museo del Oro 1987 (2024), a malformed bust is scaled up to meet the proportions of the figure at El Totumo, in Santa Catalina, eliciting an odd tactile tension between wetted flesh and cool metal. Then, we return to and revisit things we have seen before. Interrupting the sequence between an image of the blurred forms of armoured vehicles driving down an intersection (Palace of Justice Siege 1985 (2024)), and a gunman (Amnesty of Rojas Pinilla 1953 #2 (2024)) is an overexposed photo of people crowding in water, the words ‘the end’ patterning the print’s surface (Santa Marta 2008 (2024). Just to their right is a much smaller print, Marie and Claudia (2024), hung too high for close scrutiny—mother and child are captured in the joyously terse instant before physical embrace.

In these leaps across time, space, subject—and our eyes are leaping too, between each grouping of prints—Nicholson is traversing and collapsing genres of photographic visuality. The images slip between the codifications of the press photo, the advertisement, the ethnographic study, and the image record of an object in an institutional archive, which have each emerged within contexts of control and governance, inseparable from structures of colonial power. A violence patterns the production and consumption of such images, and is re-enacted and retraced optically, epistemologically, and algorithmically in a contemporary economy of images, capital, and fleeting attention spans. Nicholson is working from the fissures of these visual typologies as she turns to her archive and tests the limits of—or altogether eschews—the camera lens, allowing them to blur into and collide against each other. When her images emerge, there is an undefinable familiarity about them which arrests us. They are altogether unpossessable.

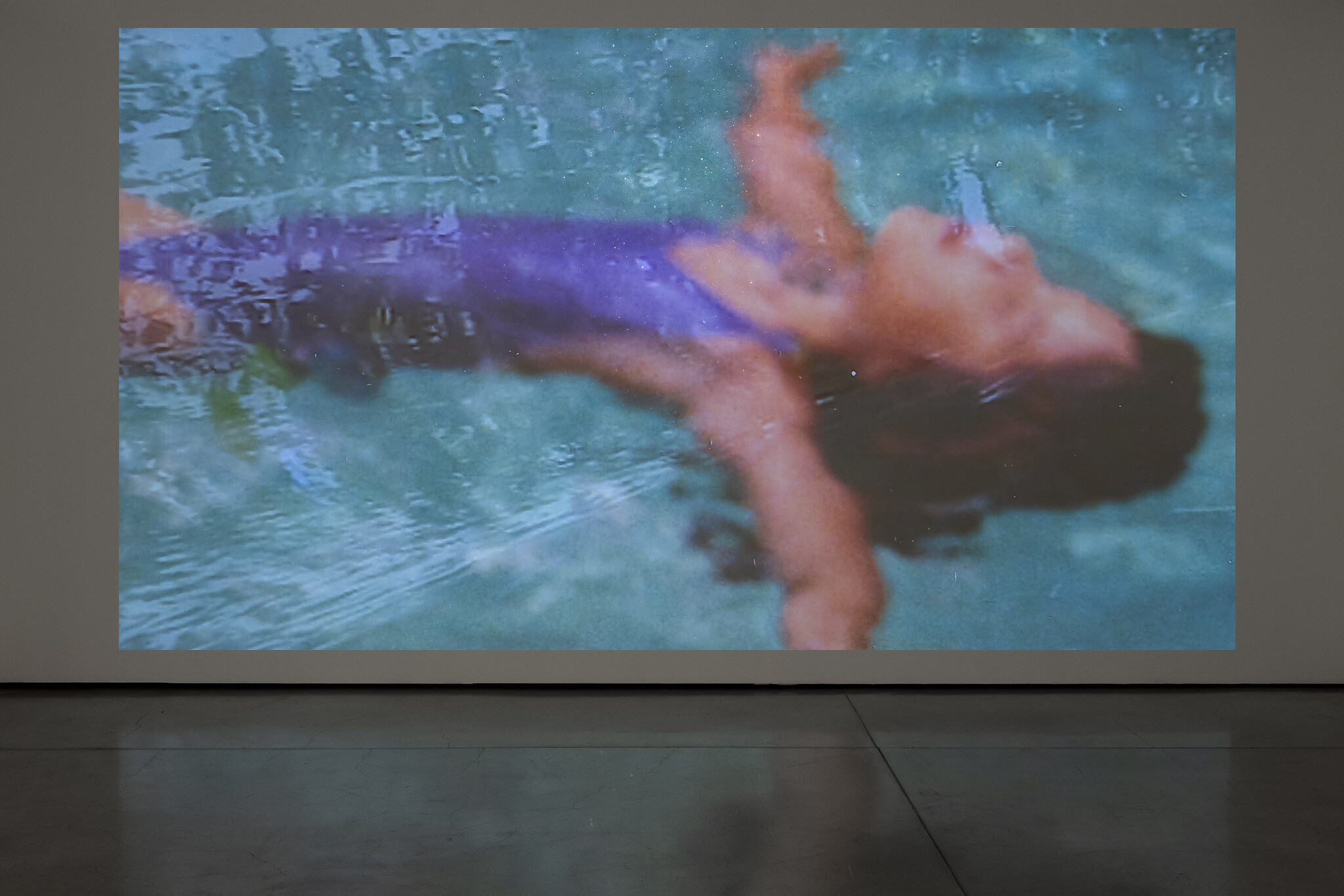

Claudia Nicholson, The Deep Rivers Say It Slowly, 2023. Single channel HD video (still). Original music by Monica Brooks. From Claudia Nicholson, If The Mountain Is Burning, Let It Burn, 2024. Installation view, UTS Gallery. Courtesy the artist and UTS Gallery. Photo: Jacquie Manning

Perhaps, this is most clearly expressed in The Deep Rivers Say it Slowly (2023). Against the dissonant tremolo of piano keys and synths in the accompaniment composed by Monica Brooks, video footage and images appear in sequence, overexposed, scratched, grainy, and blurred. We see a satellite tower, the body of a swimming seal, a pair of shoes tapping in dance on a pavement, a girl floating on the water’s surface with footage of rippling water layered underneath; we read “NO MAS”, “Colombia”, and “Forever 21.” Light and shadow mingle with no divide. A photograph pictures a man leaning against a ledge, and seconds later, the zoomed-out version appears: it is, once more, the Palace of Justice. Again and again, we return to an image we have seen before. Nicholson and Brooks simulate, sonically and visually, a sense of accumulation through repetition. Our eyes follow the paths our memory traces.

In Nicholson’s treatment of the photograph in The Deep Rivers Say it Slowly, the failures of the human hand and the darkroom mimic memory’s faults. When the light touches the water, it obscures everything within its reach. Every image in the projection shimmers in a textured way, because the wall has been painted with glitter, so that each particle is always catching and deflecting the light. Shine simultaneously expresses a demand for visibility and a yearning for obfuscation, to refuse the mastery of the gaze. Hands grip wrists, a bouquet, a plastic bag, or it dissipates into the background, and an arm becomes a band of light. We are shown the neon blue halo of a white balloon or flag, or text disintegrating at the borders of its typeface. We are so close to the image we can see all that constitutes it, and nothing at all. If the contemporary deluge of digital media and a persisting ocularcentrism has anaesthetised us to the potentiality of a photographic image, Nicholson is offering a release.

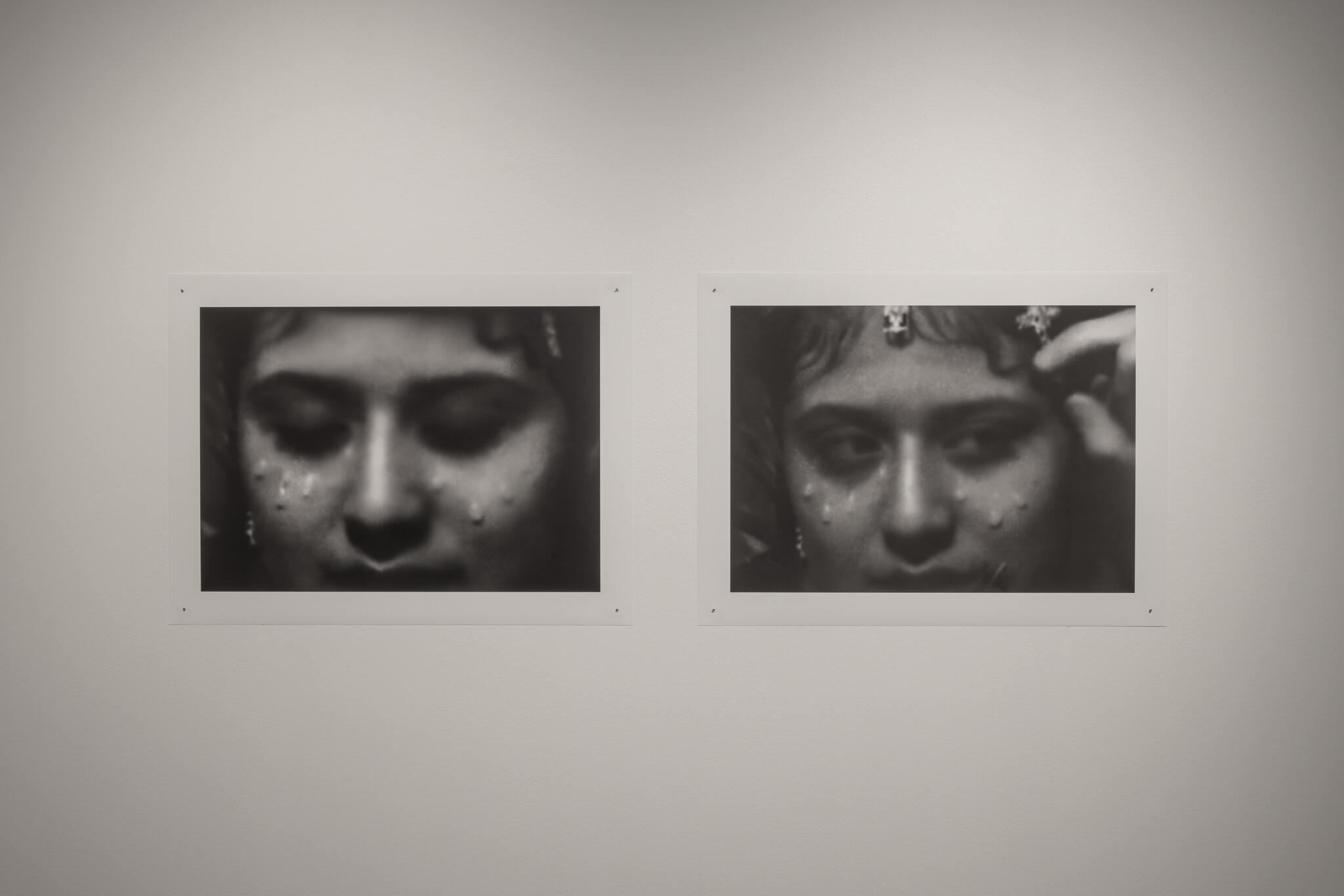

Claudia Nicholson, Self Portrait, Met Gala Party, 2024. Archival pigment prints, diptych, 52 x 69.5 cm each. From Claudia Nicholson, If The Mountain Is Burning, Let It Burn, 2024. Installation view, UTS Gallery. Courtesy the artist and UTS Gallery. Photo: Jacquie Manning

Nicholson shows us that a photograph can be cathected with desire, loss, and the feeling that you’ve seen something before, in some other time, some other place. She is in search of radical new sensualities, of other ways to (un-)attune to the visual, and the hope that something might be witnessed in a new light. Nicholson’s exhibition is about how to perceive something without seeking to rule over it, how to allow an image-subject to be opaque and refuse co-optation into fixed systems of knowledge. Briefly, it is also about pleasure. Back in the throng of prints, there are two sets of diptychs which capture the viewer in fleeting moments. Standing between the two photographs that make up Mercedes with Butterfly, (2024), and then between those of Self Portrait, Met Gala Party (2024), I think about how this is a wonderful way to spend time, stilled in the momentary lapse between the opening and shutting of eyes, or in the flutter of a butterfly’s wings. A moment is brief, never repeatable, and never recoverable. With delicacy and tact, Nicholson accepts the photograph for its infidelity and, in doing so, she renders the indistinct imaginaries of history and memory with a faithfulness that reaches deeper than the image’s visible surface.

Jennifer Yang is a writer and curator working on Gadigal land. She is currently undertaking a PhD program at the University of Sydney.