furniture, artwork, objects, books, wig by various artists, makers and craftspeople, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the Victorian Bar. Photo: Leon Schoots

The law is like a mean dancer who has practised their moves ahead of time without telling anyone else what the dance is. Although the word “law” means something laid down or fixed, deriving from the Old English lagu and Old Norse lag, it is in fact constantly moving. In principle, courts are meant to be beacons of stability and impartiality, but as we know they often fail at that. In the common law system, where judges develop legal precedents on a case-by-case basis, the law intimately co-exists with those it governs, developing incrementally through judges deciding the legal disputes at hand. As people pass through the system, a trace (stored in journals, books, databases) is always left behind. In this sense a person is a subject to law while also a contributor to it. Take the infamous Mrs Donoghue, who by swallowing a dead snail in a ginger beer bottle and suing the manufacturer, gave birth to the law of negligence. This tango between law and people deeply entwines this discipline with questions of social being-in-the-world.

In Homo Sacer: Life Unlawed, guest curators Nick Modrzewski and Jack Ky Tan put the law and its administrators on an operating table to expose its insides and investigate its outsides. Homo sacer, as the wall text explains, is a Roman law concept of a sacred man who has been removed from society for committing a crime and who is too impure to be sacrificed to the gods yet is free to be killed by anyone else with impunity. The mischievous spirit of the law even emerges in the meaning of sacer, which translates as both “sacrosanct” and “cursed or rotten.”

When we think of law and the spaces it inhabits, pompous regalia and decorum come to mind. Upon entering the gallery, the wooden cabinet leased to the La Trobe Art Institute by the Victorian Bar, an association representing over two thousand barristers in Victoria, stands solemnly in the hallway. Notably, the Victorian Bar is itself cited as an artist in the show. As an incorporated association, it has legal status like you and I, meaning that it can enter into contracts or be sued in court. Items from the Victorian Bar Collection (c. 1930—2010) has all the whimsy of the Wardrobe character in Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (1992), with Modrzewski’s sculpture of a head crowning the old wooden cabinet, giving it the anthropomorphic presence that the Bar’s legal status suggests. Inside the cabinet, various items from the collection are displayed in such a way that heightens this presence. A peruke (wig) rests on its curved stand, a jury barrel is displayed below it as a symbol of people’s active role in justice and a silver plate depicting a classic Baroque scene of Susanah and the Elders serves as a reminder of the law’s conservative austerity. As well as its capacity for justice, with Susanah’s name ultimately cleared of the alleged adultery. On the side of the cabinet, a wooden “Papuan or Pacific Island sculpture,” as the collection records describe it, hints at the extensive pro bono assistance that barristers lend extraterritorially: take it as a simple act of goodwill or a centuries-chiselled practice of the settler state’s charity. This inverted look inside the cabinet is savvily showing not only how the Victorian Bar wants to be seen by others, but also how it regards itself.

One of the most difficult and emotive debates permeating Australian society, and all postcolonial discourse steeped in land theft, concerns access to property and self-determination by Indigenous and local populations. In contrast to the Victorian Bar, which selects to present a certain position on its engagement with the postcolonial context, many harmful racist narratives are fed to Indigenous people and further reinforced through legal avenues. Kait James’s canvasses, Take Me to Your Weaver (2022) and Unjustified & Ancient (2022), employ a kitsch aesthetic to re-claim these experiences, queering the souvenir tea towels through bold colours and a gaudy collage aesthetic. In turn, generating anarchy, rebellion and a space beyond the settler-colonial gaze. As ultimate homins sacri, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities exist on the fringes of the Australian justice system yet under its constant microscope.

Issues of interiority and exteriority surface in Jonathan Baldock’s sculpture My biggest fear is that someone will crawl into it (2017). Here soft fabric hangs around a bed frame resembling a deconstructed head. A flap depicting multiple mouths is a natural entrance point, ears and eyes on the sides alert to the space surrounding them. The hollowed eyes on a hairy mask allude to an alarming interior world. The sculpture is accompanied by an ASMR-like recording of the artist’s mother, which contributes to a sensuous and unsettling environment.

I couldn’t help but draw parallels between this work and the all-time-favourite question that permeates the legal profession—what’s going on inside the judge’s head?

This question dates back to the seventeenth century when philosophers and jurists began to ponder the role of the judge and the extent to which they could steer away from the legal script. Along these lines, in 1895 Jean-Jacques Rousseau proposed a view in The Social Contract, stating that judges and lawyers possess “a superior intelligence beholding all the passions of men without experiencing any of them”. Very romantic! Albeit, Rosseau only had to live another couple of centuries to stumble upon various forms of judicial activism, political favouring in judicial appointments, as well as general macho-style advocacy that is often found in the U.S. courtrooms—a scene as mesmerising to an English lawyer as an episode of Love Island. In this sense, Baldock’s sculpture is a cunning reminder of the at times idiosyncratic nature of law-making under the command of bouche de la loi (meaning, the mouth of the law). If approached from this perspective, this work offers an opportunity to playfully consider what’s hidden behind the mouth that preaches the legal text.

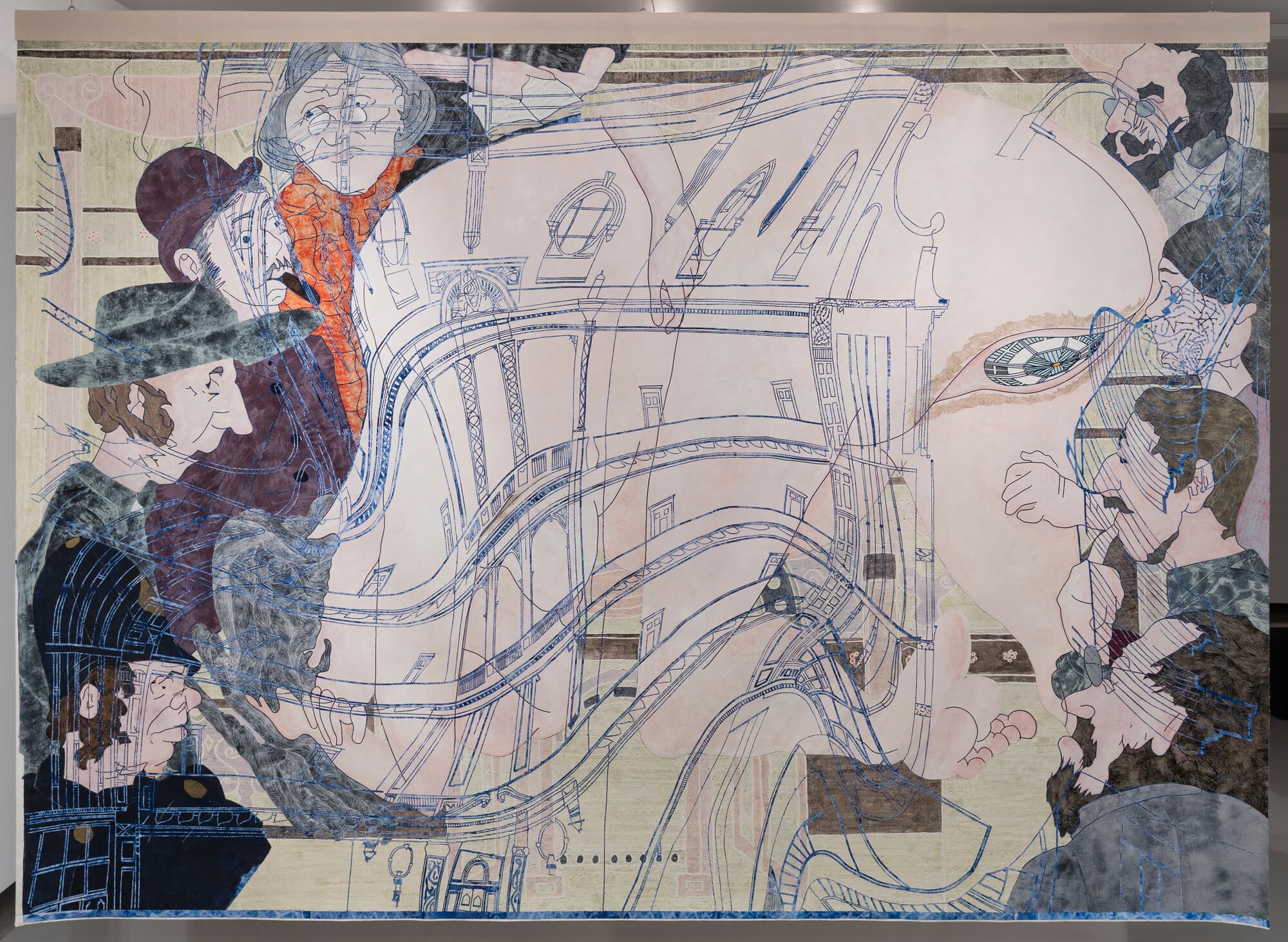

Completing the main gallery room, two large paintings, Homo Sacer (2023) by Nick Modrzewski and Leapyear Ladies Pop (2022) by Helen Johnson, are displayed opposite each other. They too point to the law as an embodied practice, but this time invite the viewer to concede their own physicality when approaching the works. In Homo Sacer, four panels are swapped to create a punctuated view of the narrative that flows through the painting. The swinging legs and hands in the crowd are severed by the apparent (re)ordering of the panels by the artist. Modrzewski’s work turned my attention to the fitness of law for the task and perhaps, an acknowledgment of its incompatibility with real life made up of luck, coincidences and simple mistakes. Like a puzzle, it doesn’t fit yet tries to provide black and white answers to a kaleidoscope of questions rooted in human experience.

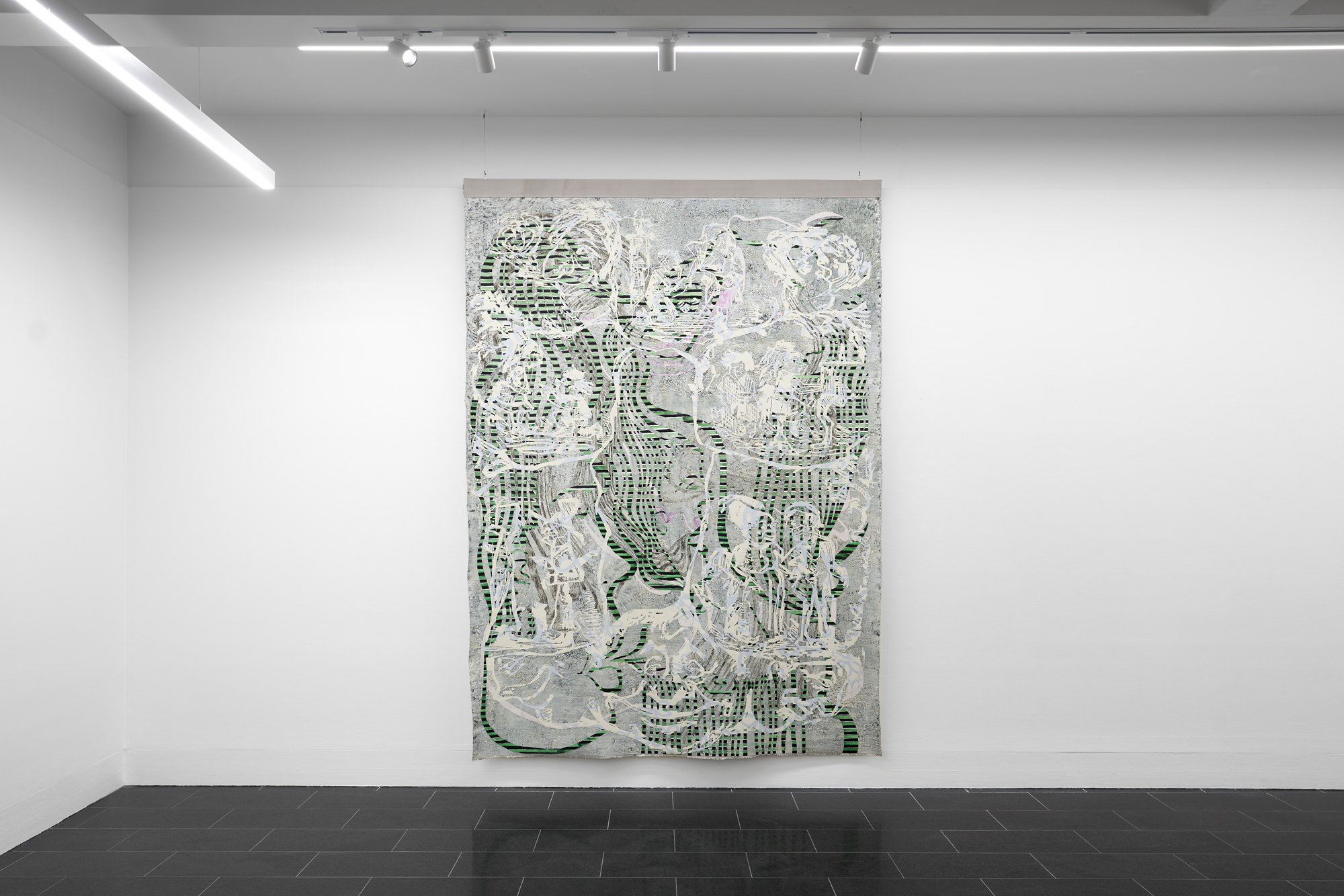

Helen Johnson’s Leapyear Ladies Pop at first appears as an abstract topographic map. But when viewed from a distance, it reveals multiple scenes of nineteenth century women proposing to men during the leap year. Amplifying the judiciary’s major role in the construction of gender and sexual norms, this work acts as a conduit for the consideration of social practices and traditions (also explored in Martha Atienza’s video works in the show) that occur under the guise of authority and demonstrate how communities create opportunities for rebellion and subversion of rules. As such, the audience is invited to step back, both physically and conceptually, to consider l’espirit de loi (meaning, the spirit of law) in relation to the spirit of the people.

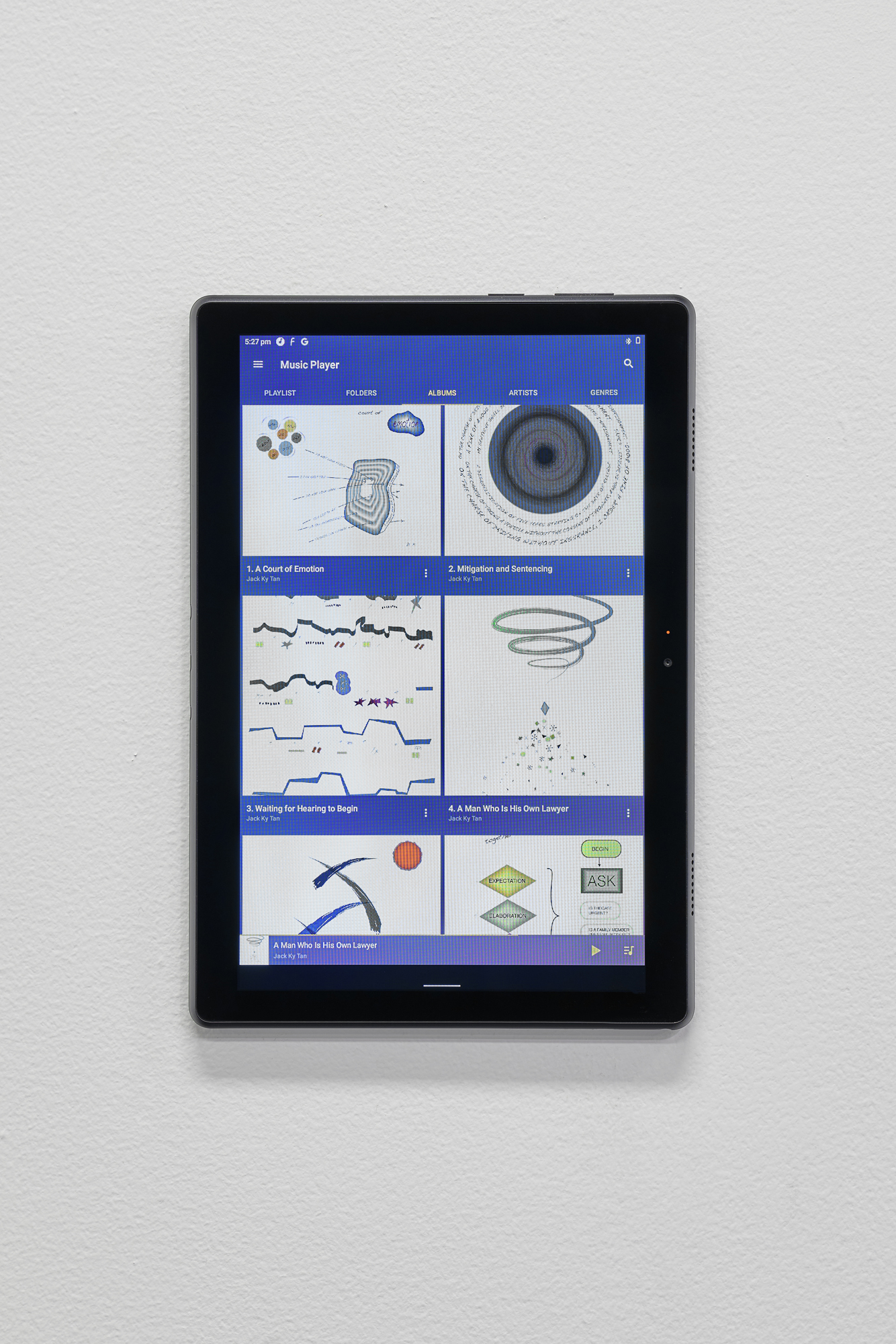

In the second room, Jack Ky Tan, a co-curator of the show, creates a kind of anatomy chamber where we can enter into the reasoning and logic of law-making to consider its emotive qualities, inconsistencies and irregularities. Eight digital prints hang from the ceiling in a disciple-like semi-circle formation. Both playful and brash, they communicate complex information in simple terms through uncanny step-by-step directions and bold brushstroke sketches that summon the atmosphere of the courtroom. This is compounded by the works’ titles: A court of emotion, Mitigation and Sentencing, My learned friend (a common way in which barristers refer to one another in the courtroom) and Appeal and advocacy. Each print comes with an accompanying audio piece that perfectly encapsulates the visuals in the prints. In Interpreting states of mind, the sound of numerous interjecting voices forms a wall of noise that gets interrupted by interrogatory claims and appeals—”who?”, “how?”, “objection!”.

Ky Tan’s work additionally draws an interesting parallel to the debates surrounding technology’s infiltration into the legal profession. Take for example the transition to an online court (lest we forget the “I’m not a cat” viral video) or the grimmer UNHCR experiments with the use of artificial intelligence in refugee status determinations. Like the law, technology is imperfect despite its supposed impartiality. In reality, as human inventions, both fields are not immune to the trappings of the “passions of men” that Rousseau naively sought to avoid. This incompatibility reveals the perpetual mess and violence that is implicit in artificial systems.

This incompatibility affects those on the fringes of society more sharply, those of us who would rather dance to a different tune altogether. Thus, the centrifugal force of (in)justice, encapsulated in Tan’s Mitigation and Sentencing, is echoed in the video works by Martha Atienza played in the auditorium of the Institute. As Our islands 11°17’19.6”N 123°43’12.5”E is streamed on the screen, the audience is invited to go underwater where a mesmerising parade across a seabed is taking place. The slowed recording of a person crossing the seabed from one end of the screen to another while holding a doll of Santa Niño (infant Jesus), is a reference to the Ati-Atihan festival that occurs annually in the Philippines. The festival is of key interest for Atienza, whose two other video works included in the show, Anito 1, 2011–2015 Our islands (2011–2015) and Anito 2, The Drug Wars (2017), record the street processions that are a part of the event. Doubtlessly, Atienza is interested in the development of a visual language, as her works employ poetic tools to explore complex themes central to her home region—labour, poverty, migration and burgeoning environmental crisis. People dressed in surreal and theatrical consumes that range from a tailor on wheels working at gunpoint to Michael Jackson performing the moonwalk in a T-shirt dress are set against celebratory images of the parade. These video works remind us of places that authorities tend to ignore, quite simply because they find themselves out of their depth, literally and metaphorically.

Atienza, who was born into a family of seafarers and grew up on Bantayan Island in the Philippines, explores the bond between her local communities and the sea in a region where almost four-hundred thousand people work on some type of vessel. The light breaking through water acts as a cinematic metaphor for salvation and hope. A topic of rich contemporary debate, the ocean presents an unusual challenge for regulators, be it in terms of border security control or the supervision of deep-sea mining by large corporations. Atienza strips this back to the simple melody of a body moving through water, which reminds me of a Soviet novel by Alexander Baliaev called Amphibian Man (1928) about an innocent half-man, half-amphibian being exploited for pearl fishing by his rival on land, Don Pedro Zurita. The amphibian-man is forced to spend the rest of his life under water, even though his lover Guttiere remains on land. This cult classic fable alarmingly foretells the lived experiences of many communities whose ability to live on land is under threat due to rising sea levels caused by Pedro-style corporate greed. This is the moment where the law is taking an unwanted pause in its dance, shutting its eyes and ears, biting its lips and laying down its wig, just for one more night.

Sofia Skobeleva (Sid Akhmed) is a writer and lawyer based in Naarm.