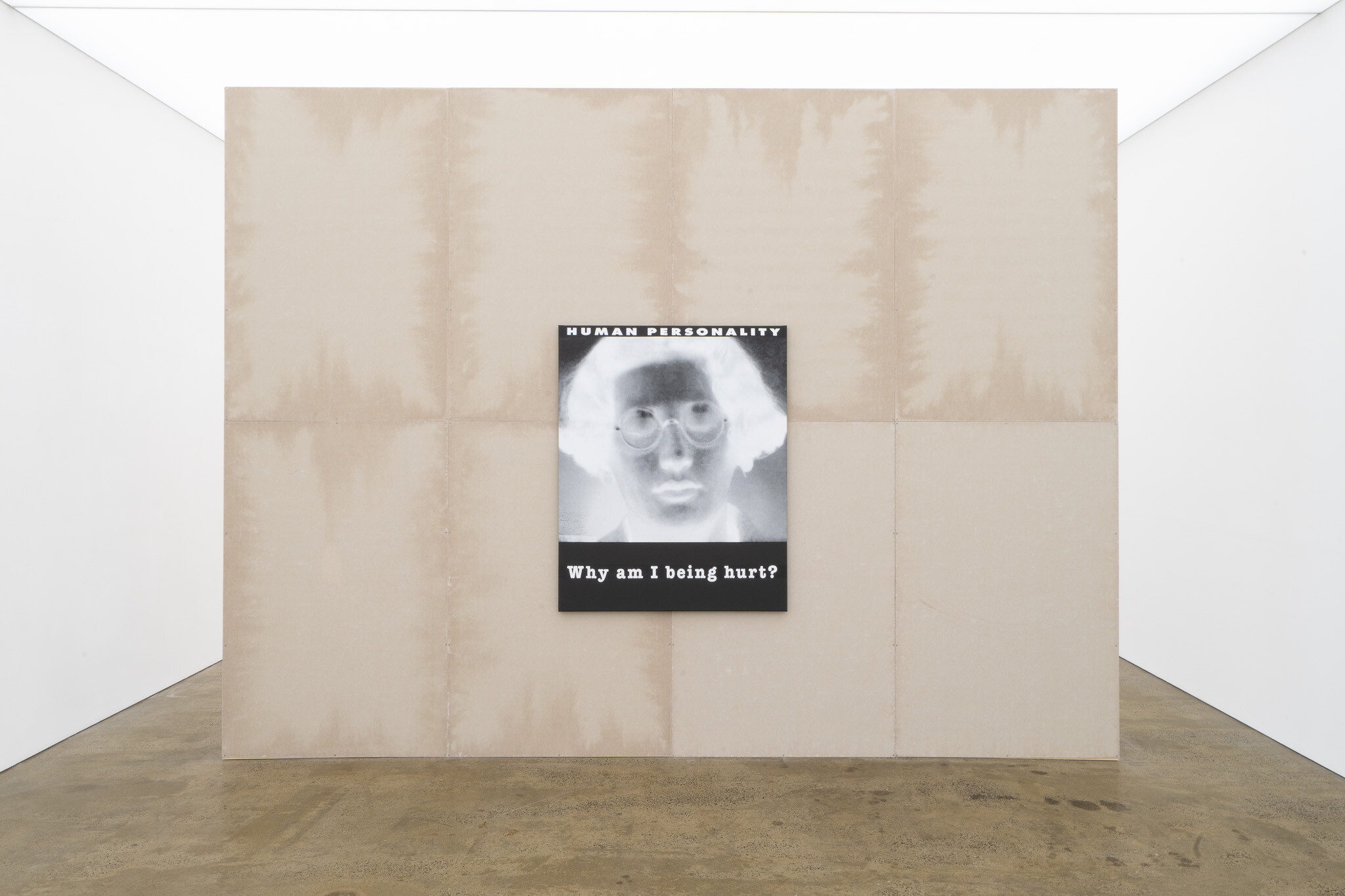

Installation view of Janet Burchill & Jennifer McCamley, Simone Weil Project: Human Personality, 2025. Courtesy of Neon Parc Brunswick.

Burchill / McCamley, Simone Weil Project: Human Personality; Janet Burchill: Solastalgia

Chelsea Hopper

Attention is the rarest and purist form of generosity.

—Simone Weil, 1942

Lining the gallery walls, we find several portraits of the French essayist, philosopher, mystic, and activist Simone Weil (1909–1943). They are all comprised of the same image, a found black-and-white ID photograph in which Weil is mid-blink, wearing her distinctive round glasses and short curly bob. It is allegedly the only existent image of Weil with her eyes closed. In an effort to find out more about it, I download the documentary An Encounter with Simone Weil (2010), where the director Julia Haslett seeks to understand the life and work of Weil. A strand in her film is an earnest pursuit to conjure Weil everywhere, in people and places. She visits sites where Weil lived and worked, including the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where she studied, and factories where she laboured to experience the conditions of the working class. Haslett’s older brother bears an oddly uncanny resemblance to Weil, wears the same styled glasses, and, like Weil, struggled with suicidal depression. She meets Weil’s niece, Sylvie, a French professor, author of children’s books and complete look-alike, who “didn’t want to imitate her life,” and goes so far as to hire the actress Soraya Broukhim in an attempt to embody Weil and “talk back” to her in character, beyond the grave.

Installation view of Janet Burchill & Jennifer McCamley, Simone Weil Project: Human Personality, 2025. Courtesy of Neon Parc Brunswick.

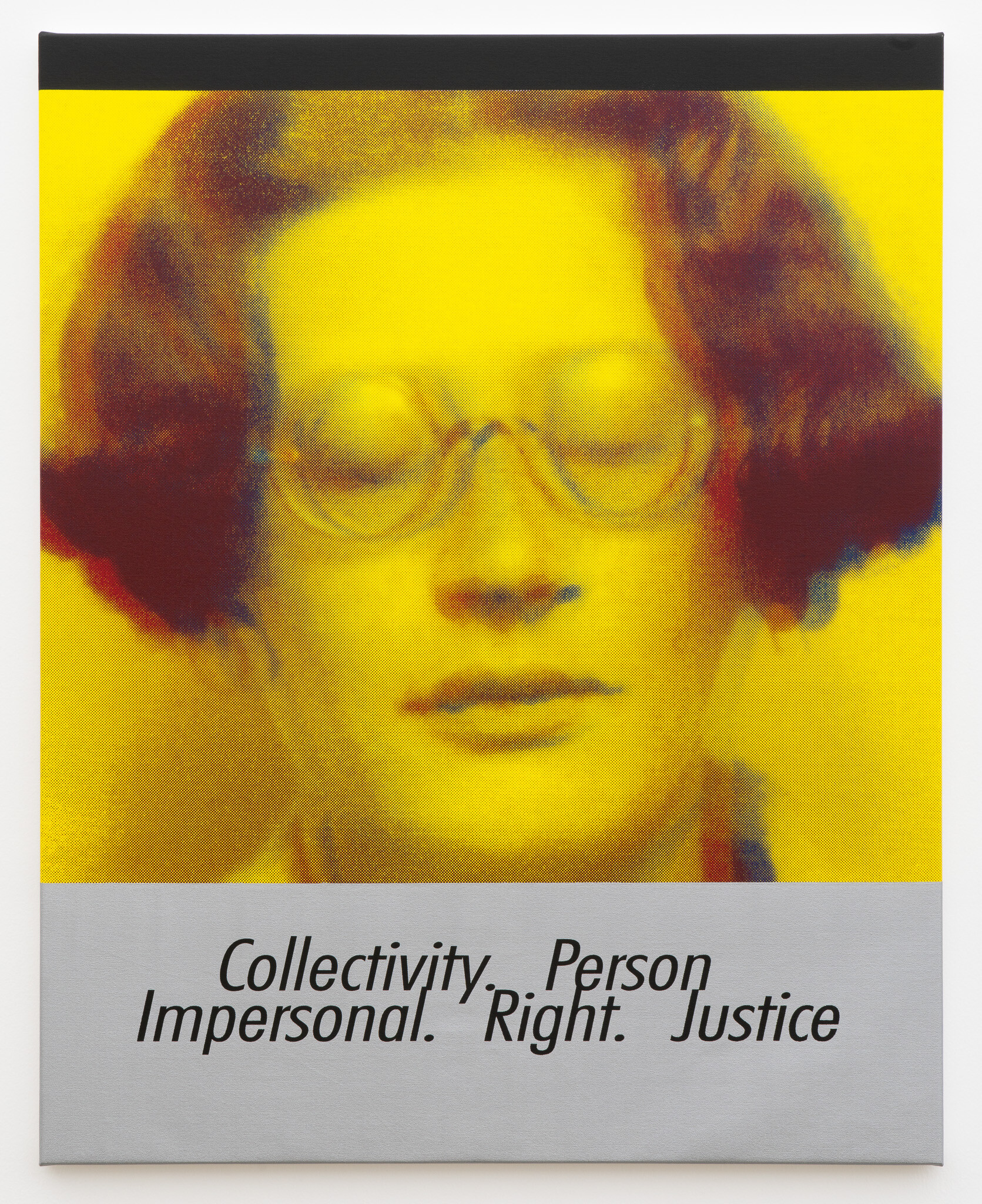

For the collaborative partnership of Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley, this particular image of Weil’s face, as they explained in 2022, “would give the greatest intensity to the series.” And without a doubt, their intentions achieve this desired effect. While they began working with Simone Weil texts in 2008, this singular eyes-closed image, blown up and repeated, made its debut years later at Neon Parc in the Simone Weil Project (2021–2022). In that iteration, her portrait appears less clear, more saturated, with a hazy effect as if it had been run through an old photocopier. Now, for their current exhibition at Neon Parc, Simone Weil Project: Human Personality, her image once again shifts in clarity. Both iterations were materially realised through the screen-printing process (thanks to the assistance of Trent Walter), with subtle changes in what appears to be the image’s resolution coupled with a simple, bright background—yellow, silver, red, blue, black, and white—colours decisively chosen for each work. In one work, Weil’s image is doubled; in another, it is starkly inverted: white and black instead of black and white.

Janet Burchill & Jennifer McCamley, Notes (Simone Weil Project: Human Personality), 2025, Silkscreen, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 152 x 122 cm. Image courtesy of Neon Parc.

Accompanying each of these rendered portraits are excerpts taken from a conceptually important essay Weil wrote in 1942–1943 called “La Personne et le Sacré” (translated into English as “Human Personality,” but literally “The Person and the Sacred”), written during the final months of her life while living in London. The words “Collectivity. Person. Impersonal. Right. Justice.” line the bottom of one panel; these are all interconnected terms that Weil wrote about in her short lifetime. In another, “ATTENTION” in bold appears beneath a sentence that covers Weil’s mouth: “The spirit of justice and truth is nothing else but a certain kind of attention, which is pure love.” Put simply, attention (l’attention) is a central ethical concept for Weil, who believed that thinking is a kind of attention. In fact, attention is one of, perhaps the deepest, form of generosity that we can offer to anyone or anything, and Weil links this thinking back to love.

Burchill and McCamley have been working with the configuration of image and text for many decades. Their Weil project recalls one of Burchill’s early word work’s I am I because my little cat knows me (1994), reshown at KINGS ARI last year, where the face of Gertrude Stein is inverted and repeated nine times, as the work’s title runs through the grid of portraits in cursive. Burchill and McCamley never let the text suggest a privilege over the image; over their career, images of women like Weil, Stein, and Tippi Hedren have performed like secular icons for them. This is why I get fixated on Weil’s portrait to begin with, and why I’m intrigued by the texts they continue to reference. However, this pairing of image and excerpted phrase edges toward the kind of aesthetic distillation that Weil herself distrusted—what she called “ready-made ideas,” which she saw as substitutes for genuine moral attention. Rather than affirming slogans or spectacle, her writing invites slowness, ethical difficulty, and a resistance to simplification.

Installation view of Janet Burchill & Jennifer McCamley, Simone Weil Project: Human Personality, 2025. Courtesy of Neon Parc Brunswick.

I wouldn’t be surprised if a third iteration of the Weil project were to appear in the years to come, as Weil’s writing is extremely quotable. Even reading the essay “Human Personality” (and the key is to read it very slowly), there are dozens of passages that could’ve made the cut. Take, for example, this sentence near the end of the essay, “Much could be done by those whose function it is to advise the public what to praise, what to admire, what to hope and strive and seek for.” Perhaps it’s this sense that she’s never quite finished speaking, that her thought, like her portrait, continues to shift, that calls for yet another return.

Burchill and McCamley are, of course, not the first to be inspired by Weil’s writing. Her legacy has touched many readers across generations. It is worth noting that none of her writings were published as a book in her lifetime—perhaps one reason we are still reading and thinking about her. She has been hugely influential to a slew of Anglo-American, Canadian, Irish, and Polish writers, including W. H. Auden, Anne Carson, Seamus Heaney, Czesław Miłosz, Flannery O’Connor, and Susan Sontag. In Melbourne, I know of a reading group (made up of mostly artists) who meet regularly to read and discuss Weil’s work. French curator Florence de Lussy, who devoted twenty-seven years to editing The Complete Works of Simone Weil, perfectly sums up Weil’s impact: “She compels everyone who reads her to reconsider their life, their thoughts, the principles that guide their life and thoughts. One can’t come away unscathed from reading her.”

Installation view of Janet Burchill & Jennifer McCamley, Simone Weil Project: Human Personality, 2025. Courtesy of Neon Parc Brunswick.

I am conscious that, for someone who is unfamiliar with Weil’s life and work, Burchill and McCamley’s Weil Project may appear impenetrable. This potential impenetrability is supported (constructively or not) by the architectural experience of the gallery, which isn’t made any easier by the fact that Neon Parc’s Brunswick space is fitted out with interrogation-room or autopsy-style lighting: there’s nowhere to hide. But one interesting outcome from my own encounter with this work is that it prompted me to get closer to Weil, a process that renegotiated the binary of you, the reader unfamiliar with the text, and you the informed reader.

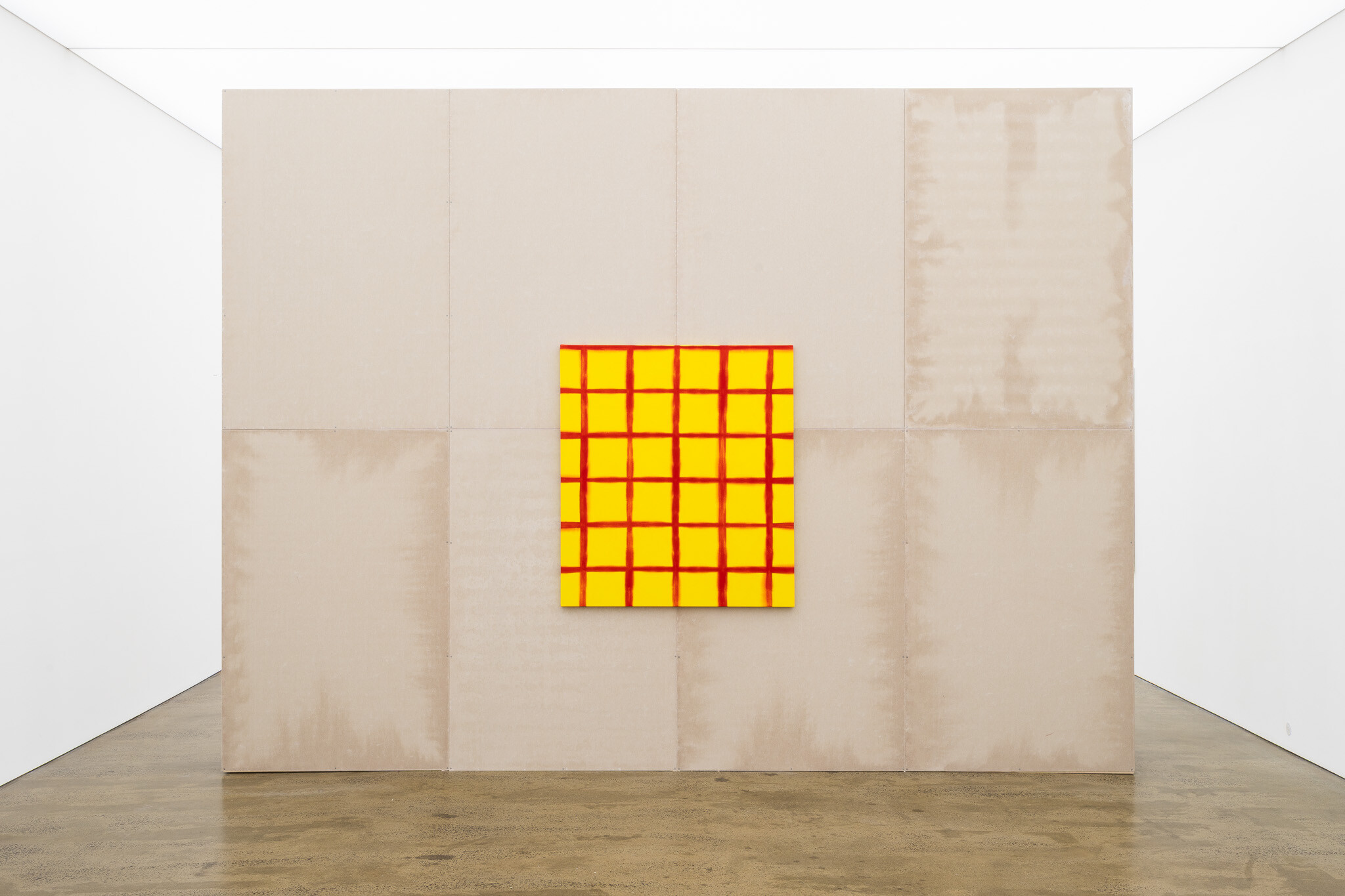

Installation view of Janet Burchill, Solastalgia, 2025. Courtesy of Neon Parc Brunswick.

Alongside the Weil Project, separated by a makeshift temporary wall, is the stand-alone solo exhibition by Janet Burchill, Solastalgia. Installed there is Burchill’s minimalist work Plot (2025), positioned at the centre of the wall made up of large panels of cement fibre board that from afar appear water-stained. Plot is a non-representational grid: a dyed sheet of calico on canvas, made using itajime shibori, a Japanese clamp-resist dyeing technique that Burchill recently learned. Up close, you can see details of the crinkled fabric and where the red lines softly bleed out into the yellow. It appears effortless, though the process is clearly deliberately controlled.

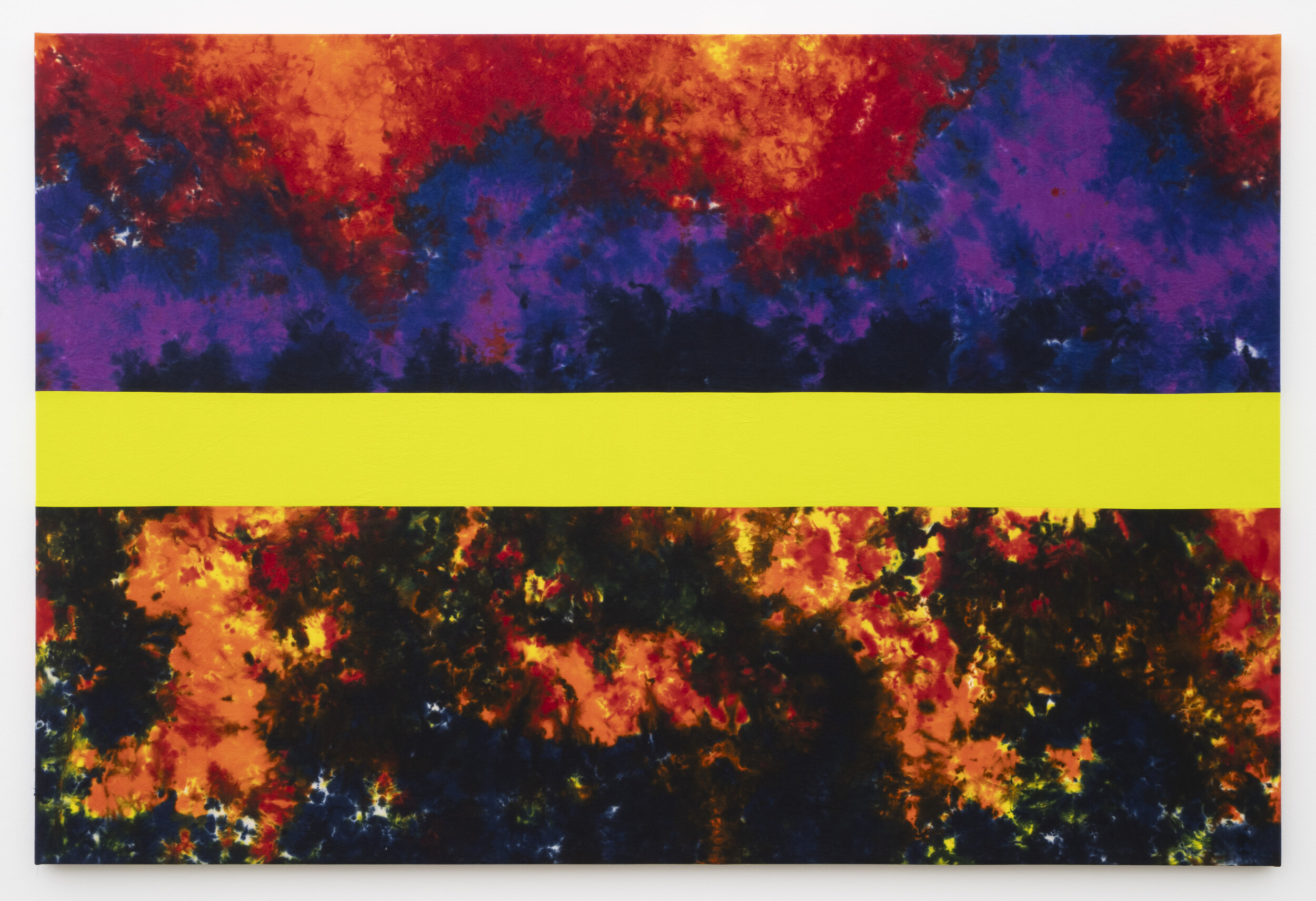

Across from Plot is a series of six works that also make use of fibre-active dyeing, though in a style more immediately associated with traditional tie-dye patterns. Fiery reds and oranges collide with deep ultramarine blues and blackened edges, creating a visual field that feels both cosmic and combustive. The colours bleed and burst across the surface in an almost celestial or volcanic manner—chaotic yet patterned, held in tension by the controlled curves of the white or black text in each work. Unlike traditional tie-dye, which often suggests looseness or ease, this application feels forceful, urgent, even explosive—as if dyed through compression or impact.

Installation view of Janet Burchill, Solastalgia, 2025. Courtesy of Neon Parc Brunswick.

Titled Solastalgia—a neologism coined by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht to describe the emotional or existential distress caused by environmental change—this series of paintings pays attention to a kind of ecological urgency. Rendered in highly controlled incandescent tie-dye bursts and overlaid with stark, silkscreened black-and-white warped letters, the works bear words drawn from a lexicon of planetary feeling: terrafurie (Albrecht’s term for righteous anger against environmental destruction), eutierria (the euphoric sense of unity with the earth), topophilia (Yi-Fu Tuan’s term for the affective bond with one’s own environment), and occhiolism (John Koenig’s poetic term for the awareness of the smallness of one’s perspective). These invented and adapted terms, bending across the surfaces like Wi-Fi symbols, bring linguistic precision to otherwise ineffable moods, where the canvases appear as affective maps of climate anxiety. The most stressful to stand in front of is Orange Tilt (2025), combining these four terms in a circle resembling a target or a warning sign—its concentric design pulls the eye inward, as one attempts to decipher the words against its searing red backdrop.

Janet Burchill, Orange Tilt, 2025, Fibre reactive dye, screen print and calico on canvas, 153 x 138 cm. Image courtesy of Neon Parc

Opposite these works hangs the largest painting in the series, Horizon (2025)—a two-metre-wide expanse split in two by a fluorescent green bar that cleaves a turbulent, blazing sky from a scorched terrain below. This bold strip diverts attention from the divided chaos, acting as a holding point—a temporary pause before total annihilation, before being consumed by catastrophe on either side. The work may make you think of any kind of crisis, littered with the visual associations from heat maps and thermal camera readings, imagining the inside of the nuclear reactor meltdown from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, or the epic apocalyptic finale of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970).

Janet Burchill, Horizon, 2025, Fibre reactive dye and calico on canvas, 152.5 x 229 cm. Image courtesy of Neon Parc.

At the end of the gallery, Burchill and McCamley’s aqua blue neon The Earth Reversed her Hemispheres (2024) looks out over the exhibition. It is a reference to a line in Emily Dickinson’s poem 378, I saw no Way—The Heavens were stitched. An earlier version of the work, made in 2021, uses the same stretched lettering of the title as an editioned silkscreen print. As a neon, I am reminded of the scholar Jane Donahue Eberwein’s point: that Dickinson is constantly seeing life as a circuit or a circle. Here, her words are caught in a loop—much like the constraints Dickinson may have experienced within the narrow confines of the church life she was raised in, but also her deeper preoccupation with scientific metaphors, repetition, circular thought, and the cyclical nature between death and renewal.

Installation view of Janet Burchill, Solastalgia, 2025. Courtesy of Neon Parc Brunswick.

Like Gertrude Stein, Dickinson is another literary figure who recurs in the work of Janet Burchill. Since 2010, she has individually made work referencing Dickinson in various ways drawing on poems 263, 362, 884, and 974, for example. Collaboratively with McCamley in 2011, they worked with poem 870, Finding is the first Act, in Bangalore, India, where it was translated into Kannada and written down a large chalkboard. Such influential nineteenth- and twentieth-century female writers, poets, and philosophers seem to live in the work of Burchill and McCamley, each circling back and forth, as if waiting to be seen, to be paid attention to. Are these quotations too “ready-made ideas” in the Weil-sense? Or, as I am starting to feel, do Burchill & McCamley transcend this citational coldness, with the intimacy of their attention?

Chelsea Hopper is a writer and curator based in Naarm/Melbourne.