Bridget Stehli, The Innocent Witch, 2025, oil on canvas, 50.5 x 37.5 cm. Photo: Hamish McIntosh.

Lantana

Victoria Gillespie

Bridget Stehli’s exhibition Lantana is like an incantation. Small and large red paintings of animals, pagan scenes, and fantastical figures peer down, circling like a coven around the exhibition’s centrepiece: a bundle of sticks sleeping on a single bed. We are in the wild zone: in between past and present, public and private, suburbia and city, performance and reality, pop culture and fine art, and, scariest of all, male and female gazes. Lantana, like its eponymous weed, escapes confinement.

We are in Nasha Gallery, a new-ish Sydney gallery occupying a loft space in Haymarket. I’m told the room has had many lives: yoga studio, anime store, internet café, and Thai restaurant. These lives still haunt the space, in the form of mysterious black marks distributed across the floor. These ghostly traces offer a nice match for Nasha’s stable of graphic artists—a younger generation of mostly thirty-somethings working the canvas in a sketchy, low-fi, almost illustrative mode.

Installation view of Bridget Stehli, Lantana, 2025. Nasha Gallery. Photo: Hamish McIntosh.

Stehli fits this mould. A painter, rug-maker, and installation artist, Bridget Stehli has specified her interests as spectatorship, gender, and fandoms. In a kitsch-y, photorealistic style, Stehli has painted male calling cards scraped from British phone boxes, used latch-hooking to replicate soft porn, and zine-d the nude male calendar. This is far from Stehli’s first show. Early this year she showed her 2023 NAS MFA grad work, An Allegorical Cave for Lonely KISS Fans, at Sydney’s Piermarq*. The “artifice-laden theatre stage” explored fantasies and our discontent with their impossibility. The installation was accompanied by nostalgic oil paintings of glam rock fans, and a video work that inverted gender roles—the men performed their sexiness in KISS-like makeup and leather garb.

In Lantana, Stehli turns from the campy aesthetics of glam-rock to those of horror. She joins a long train of feminist writers, theorists, and artists grappling with witchiness and dark magic. From 1970s surrealist painter Monica Sjöö, United States occultist Marjorie Cameron, Marina Abramovic’s noughties performances, to current Sydney art scene darling Emily Hunt, artists have used their material practices to depict (and even initiate) the occult. Hunt’s recent exhibition at AGNSW, The Grotto, and 2022 installation She Died Hard at the University of Queensland Art Museum, carefully deployed witchy and spiritual iconography in drawings, puppetry, and objects. Hunt’s subtle, researched-informed approach offers a salutary corrective to a popular culture that, often, continues to deploy the witch to demonise female agency and sexuality. One does not need to delve too far into commentary or mainstream cinema to be reminded of the pejorative weight the figure still holds.

Stehli’s theoretical referent, squirrelled away in the exhibition essay, is the Italian activist and scholar Silvia Federici. In her famous book Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body and Primitive Accumulation, Federici argued that the figure of the witch emerged in medieval Europe as part of the expansion of capitalist society. The witch was a figure not just laden with patriarchal anxieties, but a deliberate construction of the upper classes to attack feudal resistance to capitalism, and women’s resistance to gendered labour. The legal codification and successive persecution in witch hunts (femicides) was a remarkably successful tool of subjugation, wresting control of women’s reproductive labour and redirecting it towards the purposes of capitalist accumulation. Invoking Federici, Stehli is telling us that the witch—and particularly its image—has a direct relation to the means of production. It was, after all, the visual form that spread the abject idea of the witch across medieval Europe.

At stake for Stehli is, then, not so much the witch as such, but its representation. Each painting is a study of cultural and historical representations of witchcraft, paganism, and satanic panic. Decadent, bourgeois, reds and browns depict isolated subjects or cropped images on small devotional-like frames. They seem to be a ritualistic inventory of the witch’s interests; her animal companions (cats, moths, turtles), her enemy (the church), her comrades (the coven), her lover (the devil), and her contemporary audience (children). Large, obvious brushtrokes render these figures hazily, perhaps from memory faintly remembered or photographic referents. This uneasiness of photographic replication suggests the unsettling nature of image production itself. Each subject becomes a portrait of a thing, rather than a clear narrative moment. These symbols are declarative, but the relationship between them is not obvious. Their small scale means we are forced to walk close, and then confront the blank walls in between.

Historical imagery also gets a look-in. Francisco Goya’s famous Witches’ Sabbath (1798) is replicated, zoomed in to focus not on the coven of witches that dominates the piece, but Satan in deer form, who lurks in the background. Stehli’s conversation with the Spanish court painter goes beyond an aestheticisation of witchcraft. Goya used witchcraft as metaphor, arguing that the Spanish government was regressing its people by having them believe in superstition. For Goya, such ghoulish figures should only be confined to fantasies and nightmares.

Stehli’s paintings swirl and collapse time. One of the larger works, The Holdout (2025), insists again on the performance of horror. A crowd of children gather in some sort of school hall, adorned in Halloween outfits. They peer off the frame, childlike wonder bounding off their young faces. We don’t see what they are entertained by, and we spectate the spectators. Maybe childhood fantasies are a helpful addendum to reality. Adults can participate too. The Dance* (2025) reveals a Bacchanalian fantasy—bodies gather in the moonlight, beside a candlelit table of sacrificial offerings.

Bridget Stehli, The Innocent Witch, 2025, oil on canvas, 50.5 x 37.5 cm. Photo: Hamish McIntosh.

It is in The Innocent Witch (2025) that Stehli’s feminist politics of the witch are most apparent. Here, the witch appears as typically witchy, adorned with a pointed hat, long black hair, and Pagan-like robes. Stehli’s brushwork reeks of years of formal training—mature and deliberate. Her brush strokes render the background as dense and tight, but within the subject they seem to lose control. The resulting figure appears as grotesquely blurred, with blue-ish holes for eyes and a smudged red paint mark for a mouth. This smear recalls the open mouth motif of witches in western art, the hallmark of their anxiety-inducing licentiousness.

The pointy-hatted subject cocks her head, and stares steadily out of the frame. Her gaze towards us is discomforting. Here the witch seems to defy capture and objectification. Stehli’s blurry depiction of a blurry photograph allows the female referent to evade replication, and the subject has evaded alienation. The result is not an AI-generated demon, but something creepier and more abject. The titular wordplay extends this. We can’t see her because she’s “innocent”; and to be a witch is to be guilty. Or perhaps, the witch is so much a construction of the male gaze that the female gaze cannot render her.

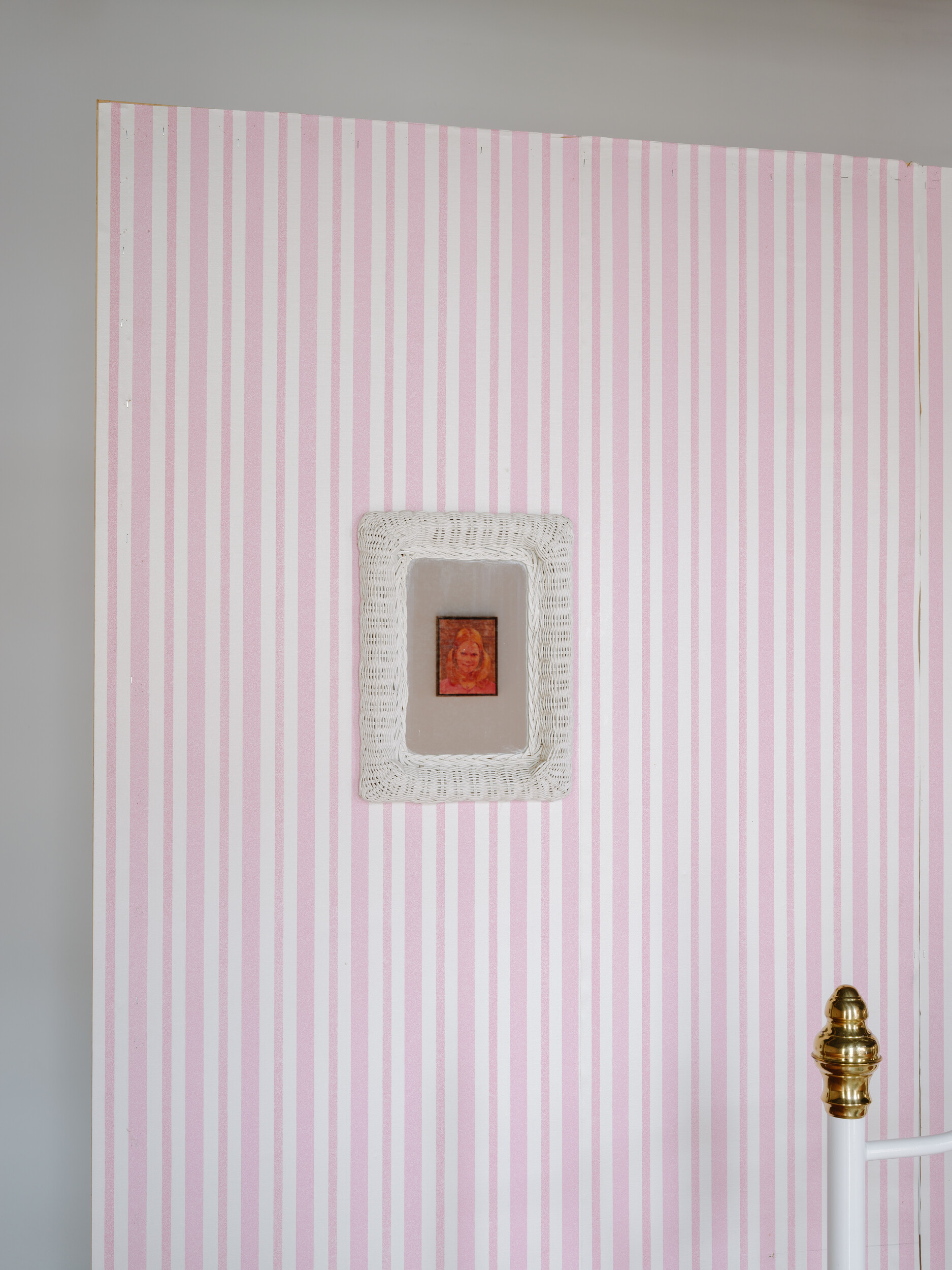

The Innocent Witch’s challenge to the male gaze, and the creepy female gaze that looks back, is spatialised by the installation that occupies the centre of the exhibition space. It is an overtly-constructed set, framing an image of deviant girlhood. On the white single bed lies a paisley doona, a precariously-positioned stuffed toy, and a bundle of sticks (referring to the low-fi horror film The Blair Witch Project (1999)). Behind, a bedroom wall is decorated with the props of girl-like innocence with pink-stripey wallpaper, ballet-themed painting, and a pink-framed mirror. It’s a middle class, 1970s movie set up. Tethering us to the real, Stehli places us in suburbia. Above the bed, sticks form the word “EARLWOOD”. Just below the ever-gentrifiying Marrickville, Earlwood is the frontier of Sydney’s family-friendly suburbia. Like all suburbs, secrets lie in plain sight. Look closely and we see the teen girl is already upsetting the etiquette required. Cigarette marks stain the wall, and, below, a half-full glass ashtray awaits its next deposit. The installation choreographs horror through juxtaposition, contrasting stuffed toys with craggy sticks and cigarette ashes. It reminds me a bit of Tracey Emin’s My Bed 1998, her visceral display of bed-bound, post break-up sadness.

Installation view of Bridget Stehli, Lantana, 2025. Nasha Gallery. Photo: Hamish McIntosh.

The mise-en-scène is quickly shattered or laid bare by the obvious sandbags holding up the plywood wall. Stehli’s eager fourth wall-breaking must be metaphorical; for our young female protagonist (perhaps the artist herself), the private is public, and the personal is political. The constructedness also reveals the cold, masculine gallery space surrounding her. The installation pins the viewer between two key sites in which the male gaze has sought to tame female agency: the public space of the gallery, where it has been looked at, and the private space of the bedroom, where it has been confined.

Yet, as in The Innocent Witch, Stehli offers a clear challenge to this patriarchal hegemony. A sepia-like portrait of the protagonist’s younger self hangs opposite the bed. The Disguise (2025) shows us an “innocent” young girl in pigtails. She’s looking back at us, and it’s uncomfortable and empowered to horrify. The mirror above the bed brings us back to ourselves and our techno-feudal present, out of the soporific feel of gallery-walking. The mirror mocks the undergraduate notion of art being a mirror—images are not just reflective, but refractive, here transforming the male gaze into something else.

Installation view of Bridget Stehli, Lantana showing The Disguise, 2025, oil on canvas, 35.5 x 28 cm. Photo: Hamish McIntosh.

Despite the complexity of Stehli’s exhibition, I find myself worrying that something more is required. As Federici said in 2020, “the most important thing feminists can do today is not only embrace the image of the witch but learn and get to know more about the true story of the women who were really accused, imprisoned, persecuted and murdered so brutally.” This in-between space could push a bit further with historical specificity, instead of hiding Federici in the exhibition essay.

However, Lantana’s witchy protagonist’s destablising gaze does help us move in this direction. The grotesque images and strange associations compel us to acknowledge our gendered and spectatorial power. In this wild zone, we confront the construction of meaning itself.

In Lantana, Stehli reminds us that witches must remain problematised. The stakes of real-world horror today are too high, as we witness the return (or just resurfacing) of a misogyny that brazenly asserts its power over women and their bodies. We are slipping into fascism, and I want some urgency.

Victoria Gillespie is a historian, writer and designer based on Gadigal Land.