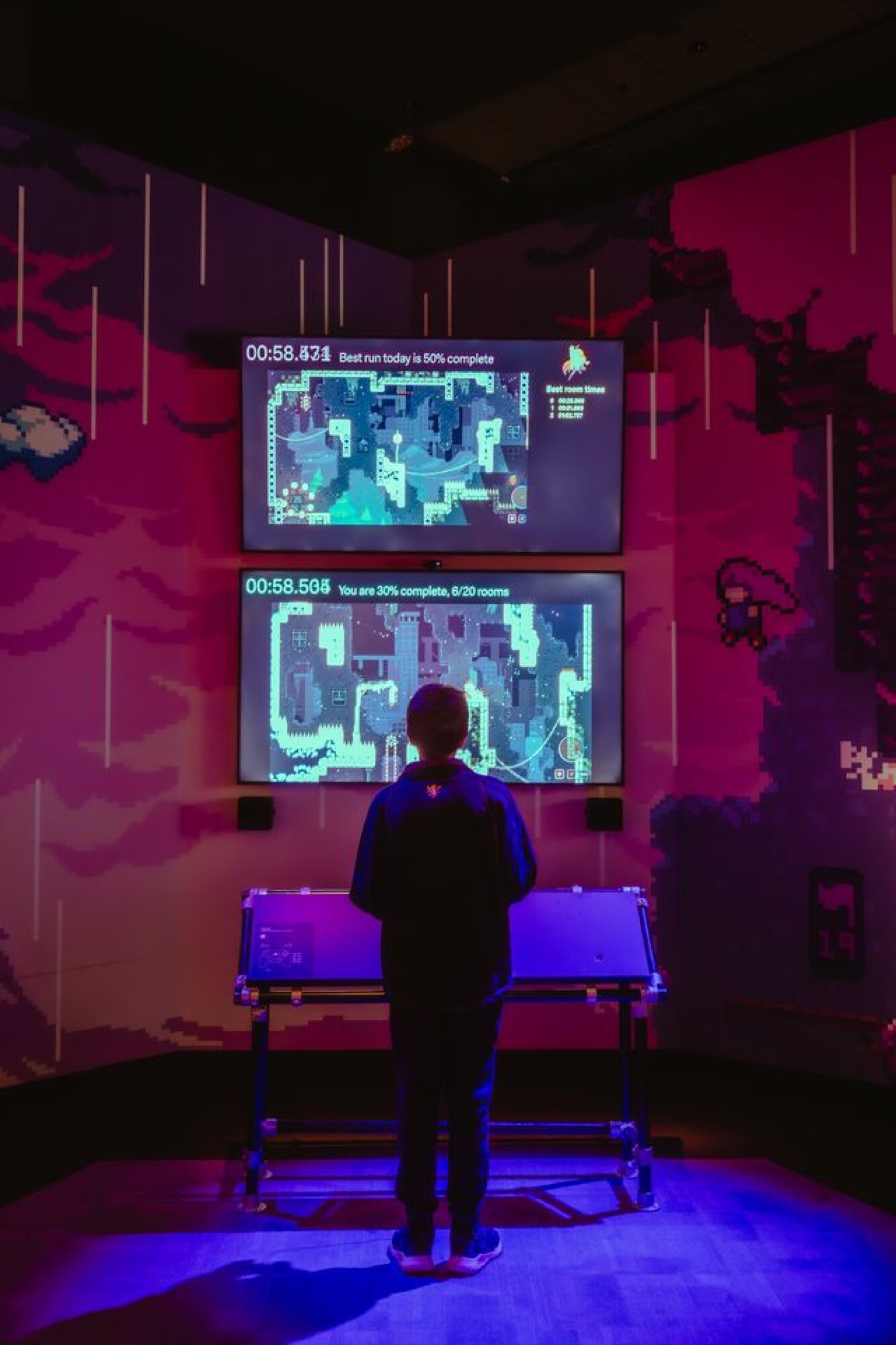

Game Worlds, ACMI, Melbourne, installation view. Photo: author

Game Worlds: Playable Exhibition

Giles Fielke

When AI takes over all standardised work, the only value humans have left is to handle the poorly defined work.

– Jensen Huang, CEO Nvidia

Have you ever considered playing the first-person shooter game Doom (id Software/Bethesda Softworks) on a plastic trinket the size of a charm on your bracelet? Neither have I. That it figures as the apotheosis of ACMI’s Game Worlds: Playable Exhibition, the reduction of an already reductive cultural phenomenon (we are all “Doomguy” in “hellworld”), is remarkable given how obscurantist this homage to the classic PC-game really is. Created by a Wētā Workshop graphics engineer and Youtuber (@ancientjames) in 2023—thirty years after the game first appeared on boxy CRT monitors—the 3D-printed LEGO brick is essentially the size of a piece of popcorn. Why this is remarkable is perhaps best understood as a feat of integrated circuit miniaturisation. According to Moore’s Law, the number of transistors on microchips doubles every two years. This observation by the co-founder of Intel has held for more than half a century. Micro-computing has irrevocably changed the world. This is our tragedy.

Doom in a LEGO brick powered by Raspberry Pi Pico R2040 and OLED screen. Game Worlds, ACMI, Melbourne Photo: Matto Lucas

Underneath Federation Square, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image provisions cavernous gallery spaces where day-trippers might, every now and then, tumble into ground-breaking exhibitions. Where once you would have found surveys of the work of the South African theatre-art maverick William Kentridge (Five Themes, 2012) or could cogitate on the thematic relationship between Spanish director Victor Erice and the Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami (Correspondences, 2008), today the cool, inky blackness of the counter-white cube is taken up with Dungeons & Dragons hagiography, Doom gimmicks, SimCity 2000 (Electronic Arts, 1993), and other digital retromania like Neopets (World of Neopia, 1999). Curated by ACMI’s Bethan Johnson and Jini Maxwell (with thanks to consulting curator Marie Foulston), these are the kinds of cathartic exhibitions esteemed critics like Christopher Allen call “galloping absurdities.” Essentially this is because they are places to play (which art galleries have traditionally not been). At Game Worlds, you will find a kind of holiday destination for when it is too hot outside, an instant reversion to our basest desires (to kill? I’m thinking of Camus’s The Stranger). Most often this is now done on-screen—formerly it was in the theatre or in writing or song—a place to distantiate and regulate human emotions. Play is—in the sense given by Dutch theorist Johan Huizinga on the eve of the Second World War—the condition of possibility for civilisation, and society is a kind of game.

Neopets, Game Worlds, ACMI, Melbourne. Courtesy of World of Neopia

ACMI, then, wants us to see in the “world building” of (mostly) video games the conditions of possibility of culture as such. But what happens when these worlds become defined by concepts such as “player-powered”? This reductio ad absurdem is what critics like Allen get right. Game worlds are not the world. We are here to effectively track the move from table-top games like D&D to screens, via genuinely exciting moments such as Infocom’s Zork (1980), and on to fully immersive worlds like Final Fantasy XIV.

Like an inversion of Doom is the commission for the City of Melbourne by Jarra Karalinar Steel, called love.exe (2024), which has been installed with a kind of modesty curtain in the otherwise chaotic, screen-filled installation design of the ACMI galleries (lots of obtuse angles, screens on the roof, etc). Made for fans of Baldur’s Gate 3 (2023), a long-standing video-game series based on the fantasy system of D&D, Love.exe features a pulsating shrine to the game’s protagonist Astarion’s e-body, making him almost close enough to touch (although only in a slightly more acceptable sense than Lara Croft’s acute bajoongas were to pubescent kids playing Tomb Raider (Core Design, 1996)). All of the accompanying information and credits are made available as didactics, floor-talks, and especially through the ACMI website, tailored to your unique visit by using the “Your Lens dashboard” function. (My code was “x9agq4,” approximating the logic, I guess, for how Elon Musk names his children.)

Students watch FINAL FANTASY XIV, Game Worlds, ACMI, Melbourne. Photo: Matto Lucas

Making public spaces (if paying $30 for entry still counts, I decide it does) a playground might be the only way institutions for art and culture will survive. Mike Hewson has recently realised this for art museums in his child-forward Sydney Modern Project (in the Nelson Packer Tank), The Key’s Under the Mat. Screening spaces, or the black-box of the museum, become about the survival of the public, otherwise out-gunned, out-played, and constantly on the run from oppressive baddies and bosses (sublimations of our day-to-day, global, labour-related hyper-father: capitalism. Again, $30). Our present bogeyman is AI. Of course, the two reflective positions—white cube or black box—are best considered hand-in-hand, and recently I have thought that the success of this “playable” mode, which (predictably) becomes “egregious” when the critics get too reactionary (Allen again), is worth reflecting upon further. Play is, after all, at the origin of art too. It’s fun!

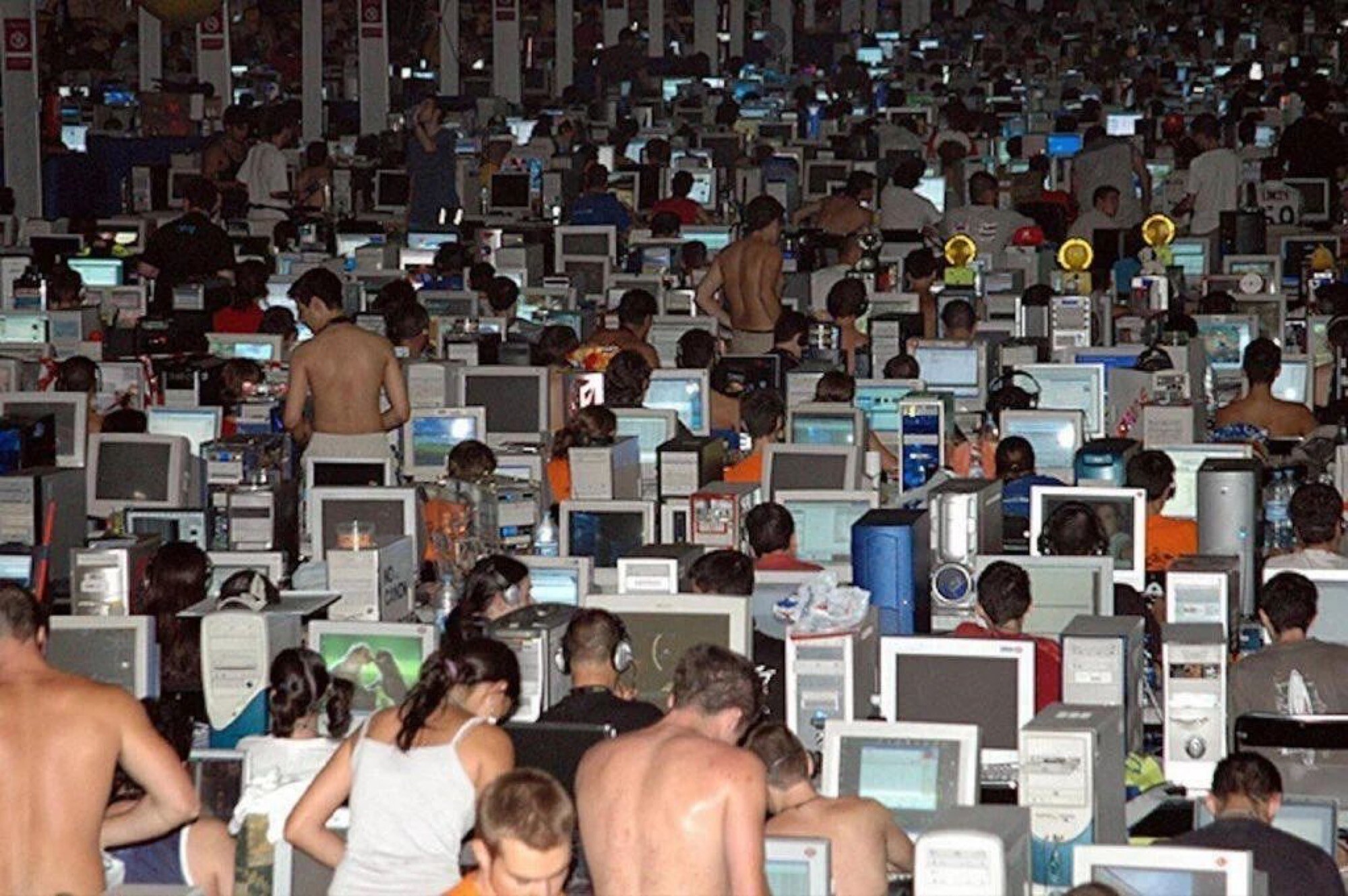

In the immediate wake of the Hanukkah massacre at Bondi Beach it feels impossible to ignore the fundamental impact of First-Person Shooter (FPS) games on the public conscious since they took over in the early 1990s. Talking points inevitably boil down to: more armour, more snipers, more firepower, more surveillance. Quake (id Software, 1996), Counter-Strike (Valve, 2000), Halo (Bungie/Halo Studios, 2001), and the corp-collectivity of LAN parties (where players link their stations in Local Area Networks) suggest palpable analogies for the broader “imaginary institution of society” as Cornelius Castoriadis named it in 1975. Where previously institutions and collections were merely the demonstration, playable Game Worlds are the lab and we test them on children. This is the experiment. Here ideology is too easily packaged as simple entertainment: groups of wide-eyed high-schoolers gaze in awe at Final Fantasy XIV, and take turns “speedrunning” an indie game called Celeste (Maddy Makes Games, 2018), where the playable character’s backstory is about her anxiety and depression.

Speedrunning Celeste, Game Worlds, ACMI, Melbourne. Photo: Matto Lucas

All of this culminates in successes like American video game and software developer Epic Games, Inc. with projects like Fortnite: Battle Royale (2017). Of course, the impetus here is to promote the Victorian and the broader Australian gaming industry, which is why Hollow Night (Team Cherry, 2017) occupies a central place in the exhibit. While I will return to the game later, it suffices now to imagine the Local Area Network has evolved to become a globally accessible digital distribution service. Recirculated images of the Dreamhack meeting in Sweden in the early 2000s, where the LAN computing retrospectively appears almost organic in the gathering sense of the collective mind (and body) of the gamers, now look like quaint visualisations of community. Dorky LAN sleepovers have instead been renovated by gore-hardened children trained to compete, to kill or be killed. Today everyone is remote, playing in a way that maximises our alienation, and where the conditions are permanent warfare.

Quake LAN party, early 2000s. Dreamhack Sweden. Photo: Reddit

LAN Party image recently published by Dazed Digital. Photo: Smiley

During a floortalk, Kriegsspiel is introduced as the modern origin of the types of game worlds presented here. This wargame emerged from the context of Prussian Army battlefield tactics in the nineteenth century. It is significant that this is the touchpoint, because there are of course any number of ways to approach gaming as such. It only makes sense today to frame all gaming as wargaming (and from this standpoint attempt to subvert this axiom). A century after Kriegspiel, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, and the Tactical Studies Rules company, took Dungeons & Dragons to contemporary gaming supremacy. This is the basic lineage for modern RPGs (Role-Playing Games). The extension of this game-type, where an avatar is selected or a character is inhabited by the player, effectively makes all gamers “players,” in the sense not dissimilar to the stage-play. The “worlding” done here, or terraforming (cf. territorialisation) is embodied, almost unsurprisingly, by the current Director and CEO of ACMI, Seb Chan, whose dedication to this subject-position is proven by the personal ephemera the curators have placed on display. Chan is pictured in photos that show him as a child of the seventies and eighties completely immersed in these emergent trends, alongside handwritten plans for routes through virtual worlds, sketched out on gridded paper.

The first product released by Tactical Studies Rules emerged out of the Lake Geneva Wargames Convention (Gen Con), and was called Cavaliers and Roundheads (Tactical Studies Rules, 1973) It was based on the English Civil War (1642–1651). Dungeons & Dragons followed soon after. Wargames and associated aesthetic effects as component parts of actual warfare have also been made the substance of contemporary art, by Harun Farocki in Serious Games I-IV (2009–10), for example. The exhibition at ACMI doesn’t seek to extend its mild-mannered critique of the military industrial complex in this direction, however. Instead, there is a video-art room that features Grand Theft Auto (Rockstar Games, 1997) “machinima” from the fifth edition (2013)—profound because its critiques of contemporary war technology companies like Palantir are found in existing game engines and remixed by artists whose names I can no longer find anywhere (after “collecting” my first hour in the galleries, my ACMI Lens stopped working). Which is to say it is cynically dystopian in the same way Jon Rafman’s post-internet work with Google Street View is too. The black box is closer to the future than the white cube.

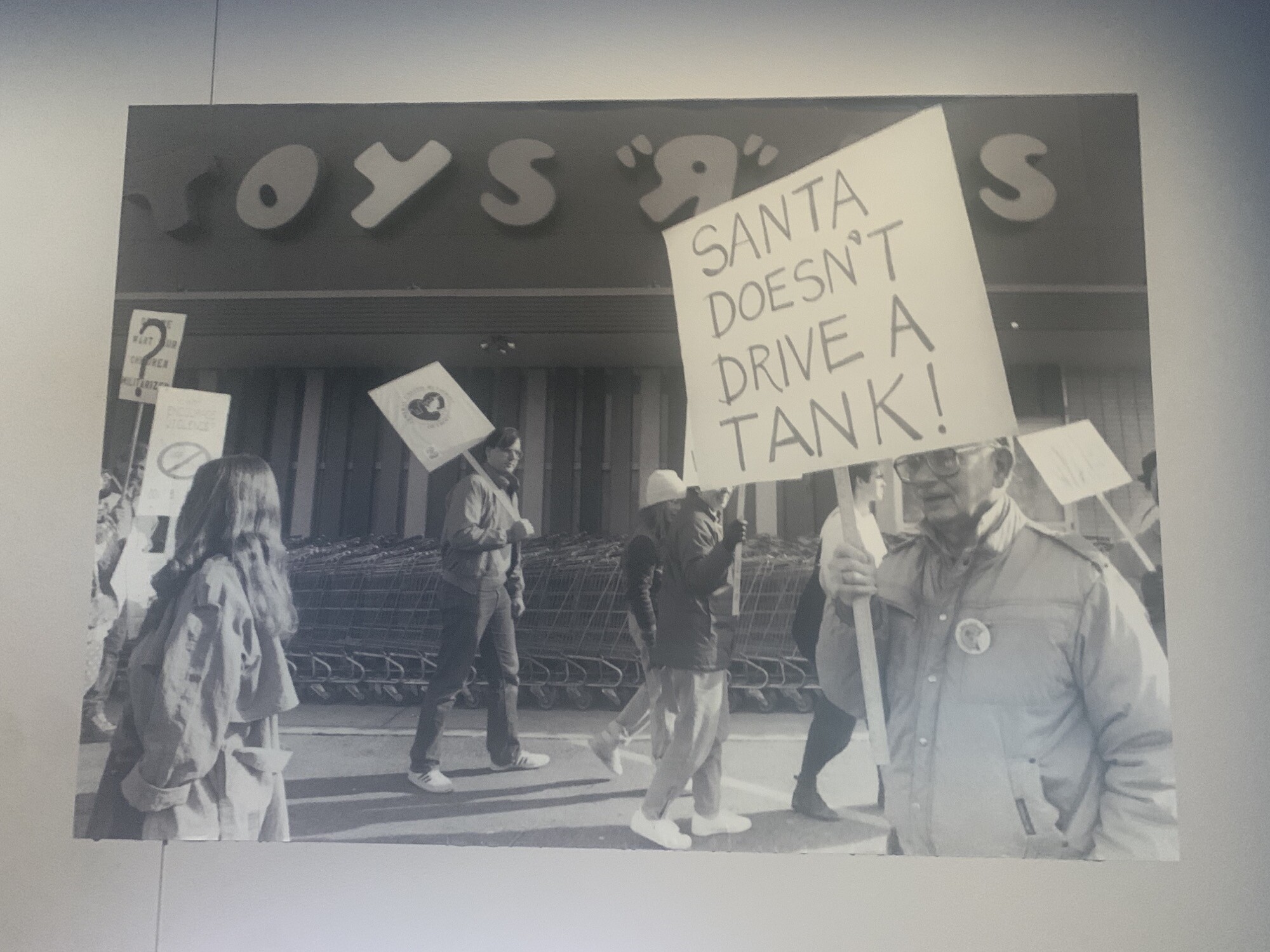

WAND (Women’s Action for New Directions) protesting in Detroit, MI, 1993. Game Worlds, ACMI, Melbourne, installation view. Photo: author

This is, of course, the same GTA that appeared at ACMI’s 2008 “celebration of games culture” (this time round it is “celebrating the evolution, creativity, and cultural impact” of the same), and while the earlier exhibit—nearly two decades ago now (and contemporary with the Kiarostami exhibition that I still remember so fondly)—was sponsored by Nintendo. The present exhibition is sponsored by another Japanese multinational, Panasonic. Interestingly, both of the companies far outstrip the current Silicon Valley tech companies like Google and Nvidia (and Palantir). Nintendo was established in the nineteenth century, so the evolution is clear: Mario is industrially-scaled fun at work (he’s a plumber), AI is not.

This segue between Japanese animation and the US-version of the Military Industrial Complex was too paranoid for my happy-go-lucky suburban-teen brain. Today it feels less conspiratorial. The cold-reality of adulthood changes all this, too late. We were just kids. Perhaps this is the secret power to the exhibition. It is glimpsed by the archival images of gamers contrasted with protests out the front of Toys’R’Us retail locations in the USA during and in the immediate wake of the Gulf War.

This leads me to Hollow Night: Silksong, the much-hyped “metroidvania” (search action) game by the Australian independent developer Team Cherry. Hard-launching during the exhibition, and in many senses the motor driving the entire endeavour, I was stuck that this is the first tip I was given by the friendly gen-X invigilator I spoke with as I entered. The hype for new-release games such as these easily trumps Season 5 of Stranger Things—which, with its own basis in D&D storytelling is not playable enough, being that it is only about abused children. We are still waiting for GTA6. In Silksong, as far as I can tell, we become a princess warrior arachnid called Hornet, armed with a sewing needle and everyone is an insect. The game play is charming, the cinematic trope of suspended disbelief is easy to indulge. The idea of working-class down-time spent completing tasks for a princess is perhaps the most apt metaphor to land on here. Since Game Worlds opened in September, Silksong has sold seven million copies world-wide.

Hollow Knight: Silksong (2025), Game Worlds, ACMI, Melbourne. Courtesy of Team Cherry

“Existence is justified only as an aesthetic phenomenon,” Friedrich Nietzsche writes in The Birth of Tragedy (1872). This so-called aesthetic justification, focused on tragedy, is meant to leads us to a metanoia, albeit a secularised repentance (God is dead, remember?). What is missing from Game Worlds, ultimately, is the aesthetic heart of existence: play. This is the lacuna when making games the object of the world. Instead it felt like I was fighting for my life. Weimar Classicist and Goethe confidant, Friedrich Schiller, regarded free play as the ultimate aesthetic venture, the drive between form and sense. Chess is not what he meant, so if Kriegspiel is the foundation for all of the games presented here: the grid, the table-top, to the pixelated screen, he was its maven. While “viduzzles” and other consumer gimmicks for gaming like the “VR” headset Oculus Rift have come and gone, pouring out faster than rounds from a gun, we remain in a permanent state of shock. The aesthetic justification for existence is scattered like shells lost to the sea. We are cosplaying at our day jobs while the real world is Elden Ring (FromSoftware, 2022) today, and next Guardian Maia (Metia Interactive, 2026).

Giles Fielke is a contributing editor of Memo Review and a Lecturer in the History of Ideas