Natalie Thomas and the Women's Art Register: Finding the Field

Amelia Winata

It is no secret that Natalie Thomas, AKA Natty Solo is, quote, “bored of white men.” The Melbourne artist who is, perhaps, best known for her blog Natty Solo and for being one half of the collaborative duo Nat & Ali has recently been on the offensive against the National Gallery of Victoria's majority male exhibition history. She has most memorably captured this fact with the slogan #cockfest. She isn't wrong, of course. And a recent attempt to represent women with three solo exhibitions—Del Kathryn Barton, Louise Paramor and Helen Maudsley—did more to highlight the tokenistic nature of the NGV's efforts to be more inclusive (the common questions being: how are these women who are mid- and late-career only now being recognised by the NGV? And where were the Aboriginal, trans, non-binary women?). In many ways, this conversation is now boring. The NGV offers an abundance of low-hanging fruit. But, on the other hand, an ongoing critique of the institution is necessary in order to induce change.

The target of Thomas's current exhibition at the Alderman, Finding the Field, is the NGV exhibition The Field Revisited, which opened this past Thursday at the NGV. The Field was the 1968 exhibition of Australian abstraction that opened the gallery's St Kilda Road premises and, to commemorate fifty years since its staging, the NGV has mounted The Field Revisited—a remake with most of the original works from the 1968 show. True to its original format, thirty-seven male artists—who include Ian Burn, Robert Jacks and Dale Hickey—while just three female artists—Normana Wight, Janet Dawson and Wendy Paramor—are exhibited. Therein lies the obvious criticism that Natalie Thomas explores in her exhibition.*

There is a history of feminist art practice at True Estate. The gallery is housed above the Alderman, a Brunswick bar that is co-owned by Elvis Richardson, who established and compiled the CoUNTess Report that has provided ongoing empirical evidence that men far outweigh women in most aspects of the visual arts in Australia. Two other women artists, Louise Paramor (the same Louise Paramor of the NGV solo) and Lisa Young, own the bar with Richardson. Thomas informs me that the Alderman is “the only 'real' artists’ bar left in Melbourne”. Richardson also runs the gallery with artist Beau Emmett, and together they appear to have recently streamlined its exhibition program and have added dedicated exhibition hours during which somebody sits the show.

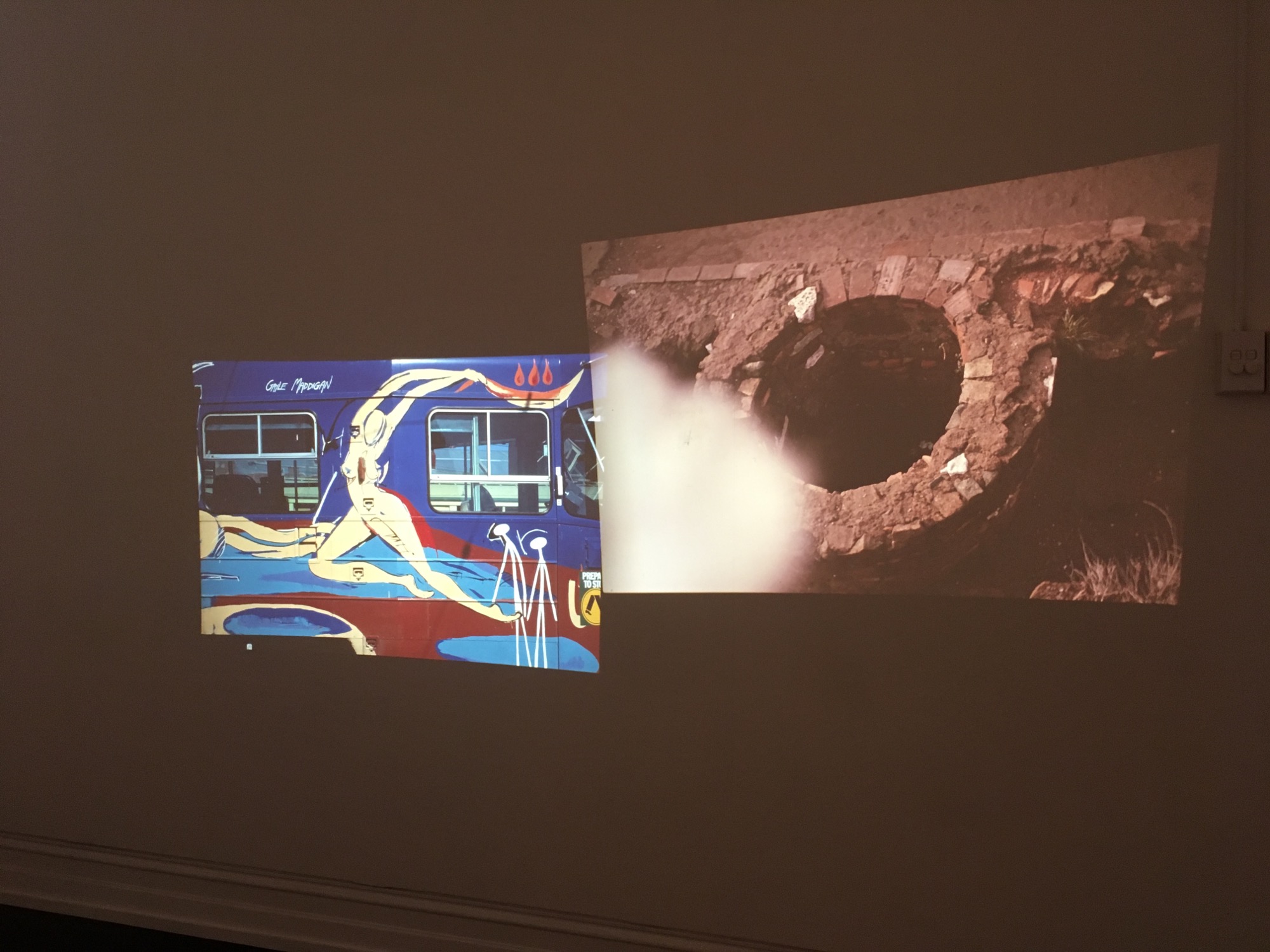

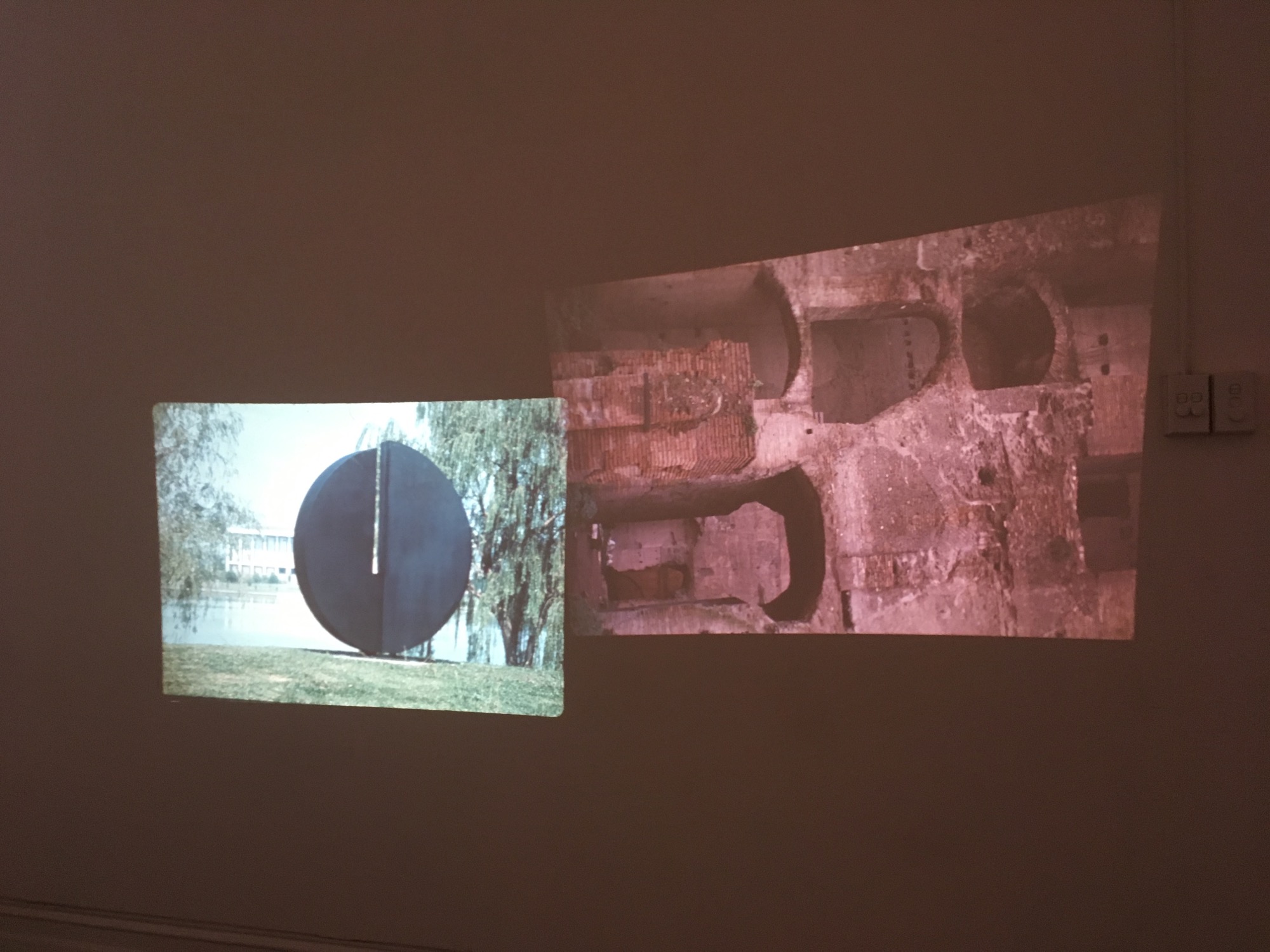

Posters created by Thomas that respond directly to The Field Revisited make up one half of Finding the Field, while a number of slides from the Women's Art Register (WAR) – a Melbourne based slide repository of works by women artists - beamed onto the wall via carousel projector, make up the second half of the exhibition. The exhibition is better understood by reading Thomas's blog post of April 11, also entitled “Finding the Field”, and, indeed, as I was informed by Richardson, the physical exhibition should be understood as complementary to Thomas's blog, which Thomas considers nowadays as her primary art form. Thomas undoubtedly belongs to a growing convention of artists using digital media as the platform for their work. Petra Cortright has made a career of it. In Australia, David Attwood's 2017 Officeworks exhibition has existed for its audiences purely in the form of online documentation, while Ian Millis's infamous Facebook page and Scott Redford's trolling of the artworld via the Guardian's online comments section represents a discursive, dissent-style form of art.

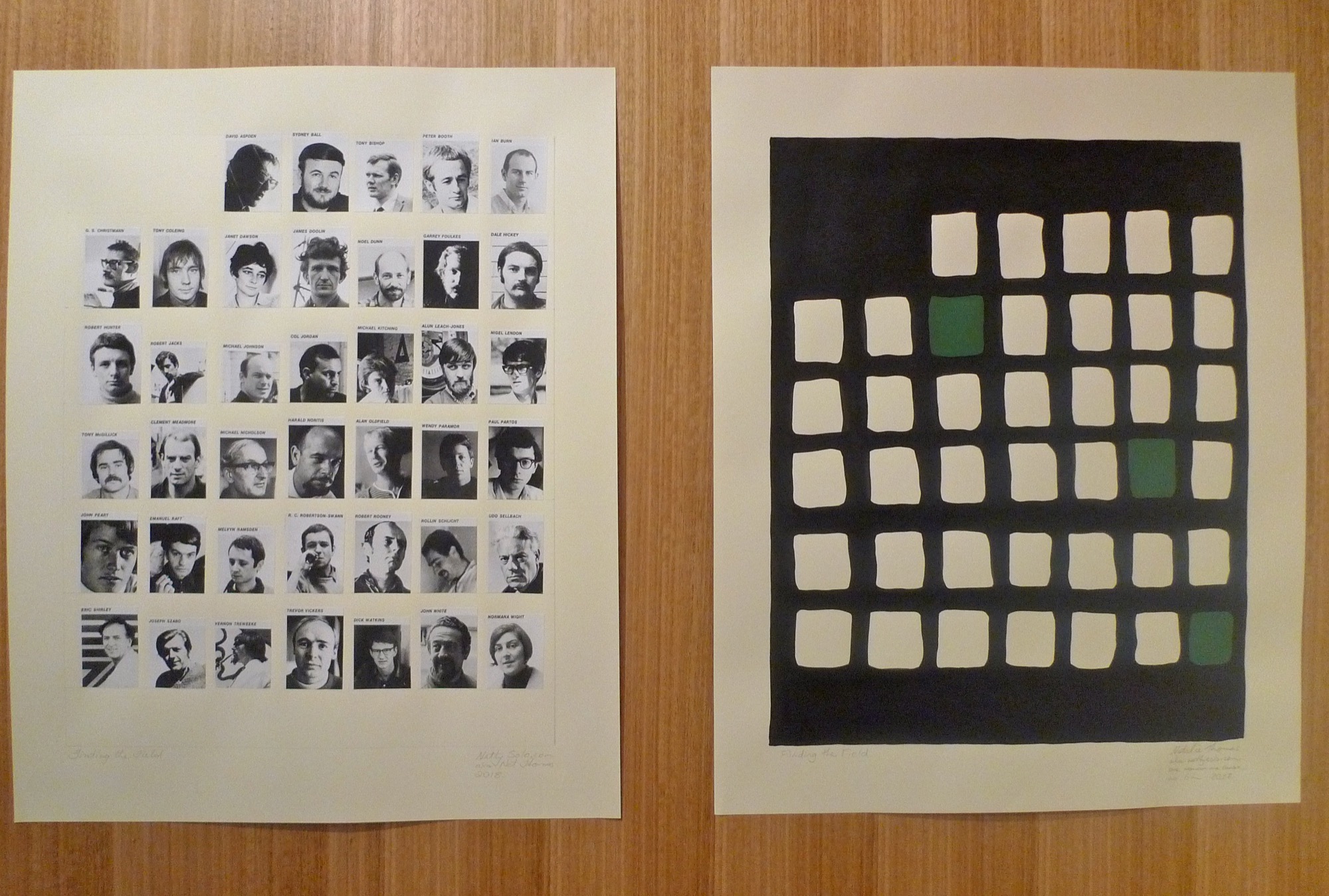

Thomas's posters take on various formats, though the majority might be loosely categorised as protest posters (was it Terry Smith who characterised the age of contemporary art as epitomised by political art?). Slogans adorn many—”we woz robbed,” “find better rich people,” “thanks Lucy Lippard (a nod to Lippard's 1975 take-down of Pinacotheca's director Bruce Pollard's inability to show her any female art in the gallery's stock room—because there wasn't any.). Other posters depict images lifted from The Field, including a copy of David Aspen's Field 1, 1968, or photographs of all artists exhibited in the exhibition that were shown in the original catalogue and demonstrate the explicit gender imbalance (Finding the Field). Another poster of 40 squares, 37 beige and 3 green, mirror the composition of the poster of photographs as well as the abstraction represented in The Field.

The works are not technically mind-blowing but, then again, I don't think that the medium of the protest poster that is being mimicked has ever had a tradition of technical virtuosity. Thomas's practice is predicated on a true understanding of the social construct of the Australian art world and a deep desire to deconstruct it by way of satire: a good example of this is her ongoing imaginary romance with Morry Schwartz, publisher of The Saturday Paper and The Monthly and husband of art gallerist Anna Schwartz, in a post called Me and Morry: my Pretend Affair with a Publishing Legend. Of course, the slap-dash aesthetic of these posters aligns with the aesthetic of her website, and an impulse to foreground what she perceives to be urgent social questions, rather than slick graphic design. What's more, Thomas has demonstrated a preference for fighting the NGV by adopting their chosen mediums of social media, hashtag, twitter-length slogans, which have become de rigueur since Tony Elwood's ascendance to the role of Director, hence “#cockfest” (my particular favourite is “year of the sociopathic babyman”, which appears to be a direct dig at Elwood). The posters thus offer comical and pithy observations surrounding the culture that institutions like the NGV represent by way of its chosen self-representation. The fact that these posters are presented on the wooden veneer walls of True Estate is a happy coincidence, evoking the period that the exhibition is speaking to.

From what I understand, the process of borrowing slides from WAR highlighted the structural problems of support for female-led arts organisations. Kiffy Rubbo, Lesley Dumbrell, Erica McGilchrist and Meredith Rogers were some of the notable names behind the 1975 establishment of WAR. Initially, 100 female artists submitted slides of their works, and today the collection holds examples of over 5000 women, trans and non-binary artists' works dating from the 1840s onwards. For such a vital resource, it is sorely undervalued. The archive operates largely on a volunteer basis with a small amount of funding coming from the City of Yarra. Originally, Thomas wanted to present slides of works artists that would have been appropriate for The Field. However, due to the fact that funding for duplicating slides is so scarce, many slides exist only singly so that most slides that fitted Thomas's criteria could not be lent.

As a result, an education pack compiled by WAR in 1993 is exhibited with, naturally, less impact than Thomas's original intention would have had. Despite this, the slides demonstrate the depth and breadth of Australian women's art production up until 1993, and the great lengths that the Women's Art Register has gone to preserve, at the very least, an index of this work. This anecdote is important because it demonstrates the massive impact that a lack of financial support has sustained on the proper dispersal and reception of this vital Australian resource, one that is perhaps a perfect example of what Thomas means by “find better rich people.” Thus Thomas's “failed” attempt to produce the exhibition she originally envisioned also proves the point she is making. Even now, female artists are underrepresented. My only grievance is that a guide to the slides was not presented to the visitor (something that curators Juliette Peers, Caroline Phillips and Stephanie Leigh did with their 2015 presentation of Women’s Art Register slides, AS IF: Echoes of the Women’s Art Register, at West Space), and so a bit of guess-work had to go into identifying the depicted works. Familiar works by the likes of Inge King are easily recognised, though some more obscure pieces would benefit from identification.

Thomas has made a career of provocation and Finding the Field is no exception: she has delivered yet another big fuck-you to the NGV. “The NGV are into anniversaries, so will it in 2025 host an exhibition to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the founding of The Women's Art Register?,” asks Thomas, perhaps rhetorically. Only time will tell. Though, it seems that, based upon what she deems a serious lack of progress in the fifty years since The Field in 1968, the forecast is less than optimistic. In characteristic Natty Solo form, however, humour acts to dull the pain.

*It should be noted that although no details appear to be publicly available the NGV has indicated that an adjacent exhibition of “overlooked” Australian female modernist artists will be staged as an annex to The Field Revisited.

Title image: Natalie Thomas, For Inspiring the Women's Art Register 1975 - Ongoing (2018). Image: Natalie Thomas)