Sky Country: Our Connection to the Cosmos

Anna Parlane

It's not often acknowledged just how much visual art comes to life through words, conversation, storytelling. Or, at least, it's not often explicitly acknowledged. It's implicitly acknowledged constantly: every time an art gallery stages an artist talk or public program, for example, or in the screeds of text published by art historians, critics and commentators. Artworks are part of a holistic culture that extends well beyond the gallery walls, and they work best when they're plugged in to that culture. If you are a member of a majority culture, this dialogue between different cultural forms is so commonplace and so easily achieved that it fades into invisibility. However, if you are part of a culture that is riddled with gaps and losses resulting from long-term and systematic attacks, it becomes much more difficult to achieve, and therefore much more apparent.

This is why it's hard to overstate the importance of galleries like Blak Dot, the contemporary Indigenous artist-run space founded in 2011. Sky Country: Our Connection to the Cosmos, Blak Dot's current exhibition, was co-curated by Kate ten Buuren (Taungurung) and Adam Ridgeway (Worimi). It's a quiet show, but curatorially astute, and it contains some strong works. The curators took the Taungurung dreaming story Winjara Wiganhanyin (Why We All Die) as a touchstone for the exhibition. Specifically, they used an animated version of this story created by the Monash Country Lines Archive (MCLA), another group doing excellent and important work. Winjara Wiganhanyin tells of Mirnjan (the moon), and the loss of his power to resurrect life. No longer able to bring humans back from the dead, Mirnjan took “onto himself the cycle of life and death”. Mirnjan's monthly renewal, which is both an acknowledgement of and a challenge to the fact of mortality, is a potent metaphor for the cultural work being done by Indigenous artists, and by organisations like Blak Dot and the MCLA.

Sky Country offers a range of artistic responses to the curatorial question of 'our connection to the cosmos,' and also to the theme of loss and renewal expressed by Mirnjan's monthly rebirth. The fruits of a collage-making workshop with young artists led by Peter Waples-Crowe (Ngarigo), displayed as billboards in a new display space on the gallery's exterior wall, are collectively titled Berrin Ngawiin Ningula-bil (New Moon Shining). Gabi Briggs's (Anaiwan and Gumbangier) Tkaranto to Naarm and Back also speaks of forming new connections by collaging together fragments. Briggs's comic-style digital illustration maps the spatio-temporal dislocation of “travelling a songline at the speed of light” and connecting to her home and lover from Canada via Skype and SMS. Where these works evoke an effort to reassemble something that has been fragmented, others by Edwina Green (Palawa) and Neil Morris (Yorta Yorta) describe the artists' reconnection with country as a foundation for culture and identity. In Green's words, her near-hieroglyphic painting of Tasmania's unique skyscape is about “building a bond with the land where I am from”.

For Green, being on country is of paramount importance to her practice. “(Melbourne) isn't my country,” she explained. “I would never take something that isn't mine and use that.” All of the artists in this exhibition have been dislocated from their ancestral land in some way. Members of the Australian Indigenous diaspora, they approach the sense of emplacement that Green describes in different ways. Timmah Ball's (Ballardong Noongar) video Haunted addresses the many ghosts that inhabit her ancestral country. Haunted juxtaposes melodramatic 80's video footage of the supposedly haunted York hospital, where Ball's mother was born, with a soundtrack of her mother's own stories of the place. Superimposing Indigenous experience over settler ghost stories, Ball's work draws out some of the overlapping and disjunctive realities (physical, metaphysical, historical) that form a place. Worimi man Dean Cross was raised on Ngunnawal country, and his exquisitely luminous painting kurruwon koora (summer night – Ngunnawal country) clearly articulates his connection to this place. In Cross's poetic words: “As the day's dying light fades, the dawn of evening begins … Usually, there is a brief shining moment of stillness, where one is neither here nor there.”

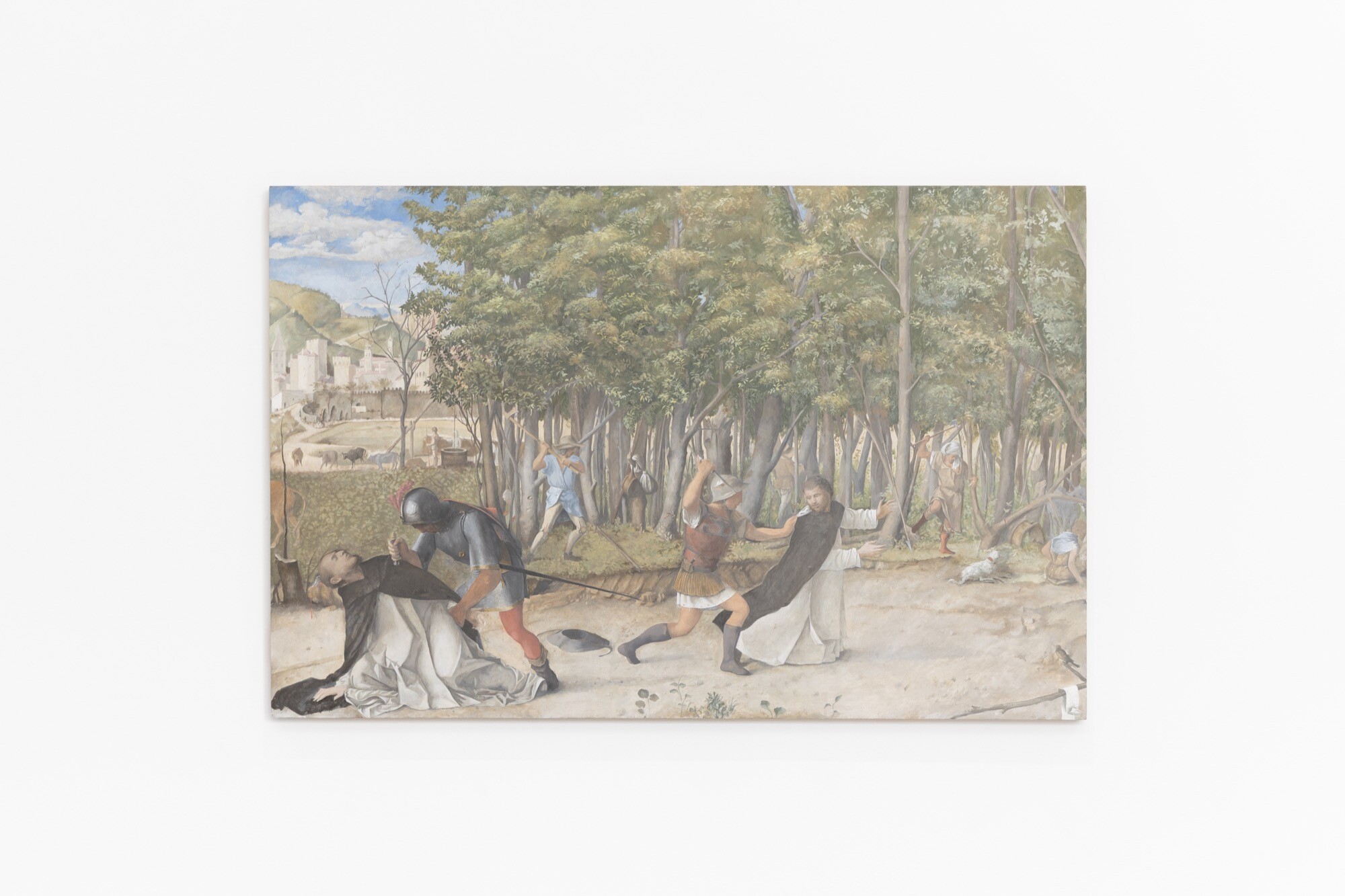

The curators write in the exhibition catalogue: “In facing a reclamation of knowledge, we must acknowledge a living history of its disconnection. This disconnection is a history of bloody conflicts and inheritances of trauma and shame. To reclaim is to speak back to that imposed shame and to rename it”. Julu/Everything by Katie West (Yindjibarndi) speaks back to this history with beautiful clarity. An earth-coloured (“bush-dyed”) wall hanging, the delicate, gauzy fabric has been embellished with a scatter of stars: some hand-embroidered and some cut from cheap plastic Australian flags. Each star, as the catalogue text explains, represents a particular Indigenous life lost. West's re-use of the national flag's southern cross (a symbol, unfortunately, currently associated with militant and racist white nationalism) reclaims the southern night sky, in a work that is a memorial to loss, a protest against the Australian state's failure to protect Indigenous health and welfare, and a step towards cultural reconnection. West writes: “Julu means everything in Yindjibarndi language. Like specific knowledge related to the night sky, language is not something I was able to inherit directly. Naming this work in my Grandmother's language, for me, is a personal act of cultural renewal.”

Working to stitch back together something that has been pulled apart is a process that MCLA director John Bradley calls 'decolonising.' The MCLA team builds 3D animations of Indigenous stories, narrated in their correct language and staged in an animated reconstruction of country as it looked prior to colonial development. Significant sites are therefore reconnected with language and narrative in short videos that are designed to be used as intergenerational learning tools and triggers for further conversation. The urgency of MCLA's work is indicated by the fact that their video of Winjara Wiganhanyin contains the first recording of the Taungurung language made in over a century.

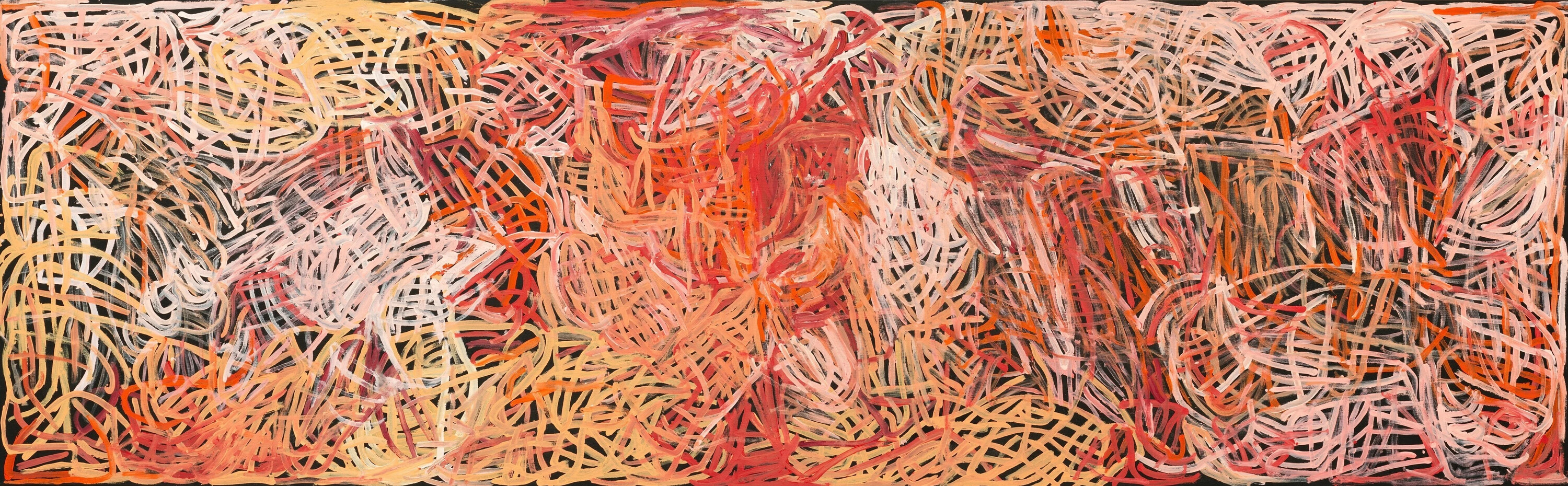

I witnessed the way that stories, artworks and country fold into one another at the artist talks held at Blak Dot last weekend. Artist Hayley Millar-Baker (Gunditjmara) explained that Country at Night, a circular installation of 71 rocks borrowed from her birth country, Wathaurong, comes from a special spot near the You Yang mountains where she goes to rejuvenate. What Millar-Baker calls “deep listening” is something that she does “at night time, on country.” At Blak Dot, discussion of the work centred on its resemblance to a campfire, moon or meeting place. For me, a non-Indigenous art historian, Millar-Baker's borrowed rocks also recalled Robert Smithson's non-sites and Richard Long's ecological-shamanistic stone sculptures. Other audience members formed a connection with the volcanic rock plateaus of Millar-Baker's Gunditjmara ancestral land. The artist told how the rocky Gunditjmara landscape was not only useful for her ancestors' famous eel farming waterways, it also provided them with a refuge from colonial aggression: the ankle-breaking rocks hidden in the long grass could not be easily navigated by foreigners, or on horseback. As these and other stories were told, Country at Night acquired new density. The work formed the centre of a conversation about connection and disconnection from country, the pain of loss and change, the spiritual regeneration offered by the open night sky, and the work of cultural renewal.

Anna is a writer and occasional curator based in Melbourne. She is currently finishing a PhD at Melbourne University, and was previously assistant curator at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Title image: Hayley Millar-Baker (Gunditjmara), Dark 1, Dark 5, Dark 2 and Country at Night (installation view), courtesy the artist, Image: Steven Rhall)