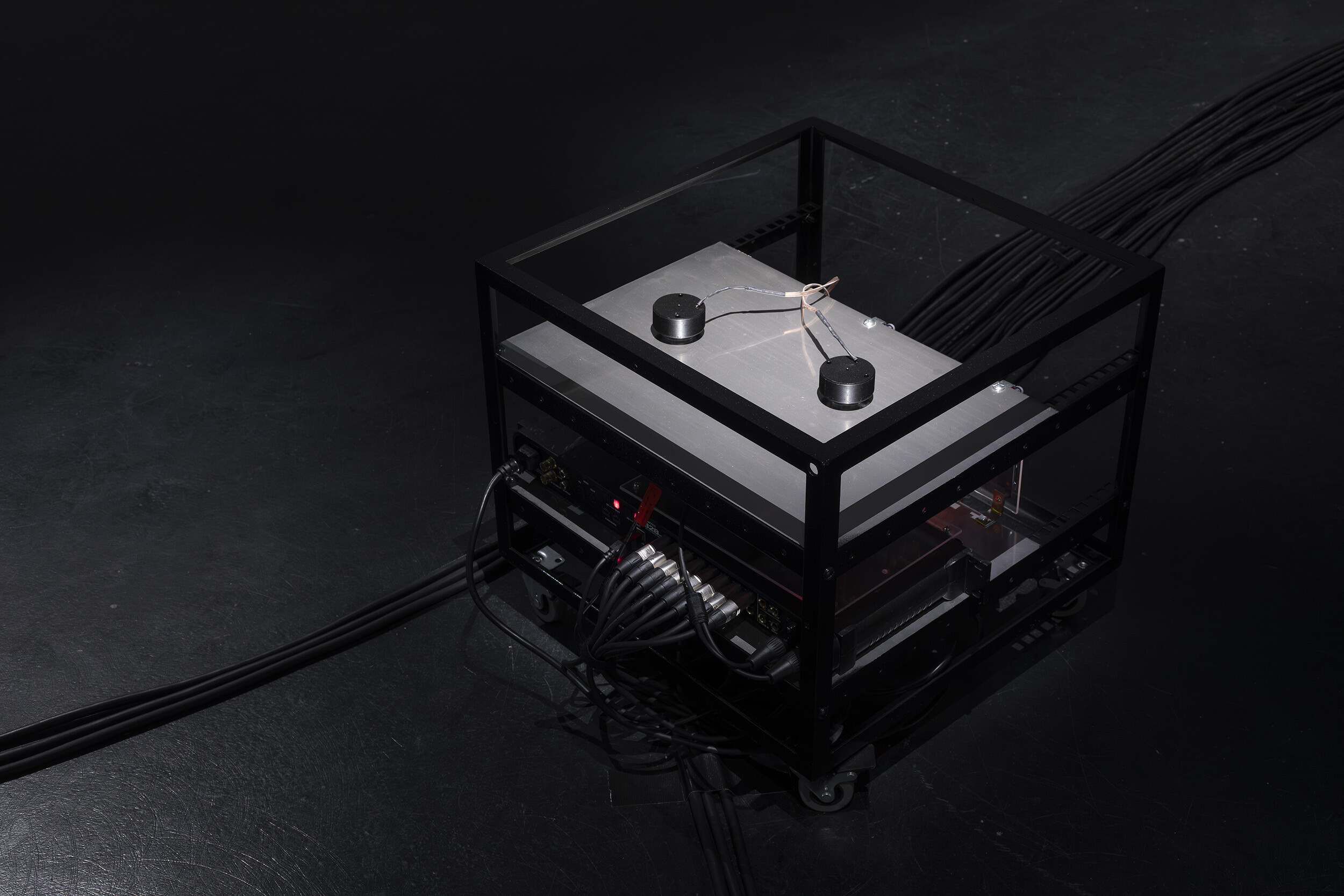

Installation view of Lewis Gittus, Resonant Entrails, 2026, Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

Resonant Entrails

Philip Brophy

Lewis Gittus’s PhD completion exhibition, Resonant Entrails, held at the Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery, was a succinct distillation of his exploration into corporeality and its aural implications as considered through the lens of Gothic literature, presented through two works. The first was A Swarming of Points (2026), a ten-channel audio and single-channel video work that ran on a twenty-five-minute loop, with a timecode displayed on a seven-inch screen. The second was The Mysteries of Udolpho (2025), a wall work comprised of 703 pages taken from two copies of the Oxford World’s Classics 1966 edition of Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), where the artist had meticulously altered the pages with permanent markers and water-based inks.

In some respects, the two works were ontologically opposed, yet they each in their own way traded in a type of “unwording” and “unimaging” by figuring literature through blackout poetry, and sculpture through sound installation. Each work absented a recognisable form to accentuate a palpable presence or residue. The booming bass drones of A Swarming of Points, overlaid with aural textures and waves, pushed the visitor’s imagination into auditory impressions and memories of being unsettled by the dark. The erased, redacted, and defaced pages of The Mysteries of Udolpho’s splayed novels enticed the viewer’s imagination to construct significance from the random phrases and tessellated sentences held in black voids.

Lewis Gittus, The Mysteries of Udolpho, 2025, 703 pages taken from two Oxford World’s Classics 1966 editions of Ann Radcliffe’s Gothic-romantic novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho, altered with permanent markers and water-based inks, Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

This latter work clearly announced its preoccupation with the Gothic. Tiled in thirteen rows of fifty-four pages, the grids were abstracted to the eye from a distance through the predominance of completely blackened pages. An overall pattern of organic logic was generated by black ink forming misshapen areas of darkness on those pages that revealed their pale, yellowed underlay. Close inspection allowed one to read the playful randomisation of the original text through the technique of blackout poetry; however, one could also choose to refrain from reading and instead savour the delightful snail-trail smudges and filigree gaps that created non-blacked-out veins resembling lightning bolts of discharged electricity in the atmosphere. The technique of blackout poetry bears a Surrealist legacy, sporadically appearing in various guises throughout the multilingual publication 391 (1917–24), edited by Francis Picabia. A more recent variation would be the amazing self-published books by Crispin Glover—Rat Catching (1988) and Oak Mot (1991)—which have formed the basis of his occasional “slide show” performances over the past few decades.

A less direct impression of Gittus’s The Mysteries of Udolpho would be how this wall-piece occupied the gallery space. It was the only wall illuminated by track lighting in the broken-plan outlay of the Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery, and the last wall one encountered when entering the primary rectangular space abutting the oddly-placed staircase angled onto the smaller, secondary room. In a low-key manner, visitors ventured on their own mini-Gothic foray into the dark to arrive at this work, glancing sideways at that dark wooden staircase which leads God knows where. In this setting, the work felt like the archetypal serial killer’s hieroglyphic plan; the only thing missing was red string cryptically tying together details across the mapped wall. All told, the space welcomed the associations that a darkened “black box” gallery environment has with the manifold dungeons, corridors, stairwells, and watchtowers spread throughout the many chateaus, castles, manors, abbeys, monasteries, and prisons of canonical Gothic literature.

Detail of Lewis Gittus, The Mysteries of Udolpho, 2025, 703 pages taken from two Oxford World’s Classics 1966 editions of Ann Radcliffe’s Gothic-romantic novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho, altered with permanent markers and water-based inks, Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

From its Surrealist undercurrents to its Modernist surface, the black-and-white distribution of what could pass as concrete-poetry texts awaiting performative interpretation also bore a Fluxus aura. But while that line of enquiry leads into the twentieth-century project of expanding the action of writing to form radical contrails in literature (Stein, Joyce, Burroughs, et al.), one should not assume that Gothic literature be excluded from radical potential. Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho—like formative eighteenth-century novels Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) and Clara Rees’s The Old English Baron (1778)—inherits and conforms to the notion of Romance: employing excessive literary description to accentuate sensation. Important to note is that these lurid multi-chapter sagas not only degraded the lofty ideals of Enlightenment écriture, but also lent themselves to be cannibalised by the populist publishing channels of the time. Serialised and condensed in “chap books” and “penny dreadfuls,” these Romances reduced plot and character further, and accentuated the drawn-out detailing of suspenseful and shocking moments. The unfiltered impact of these scenes are the germ of what would grow to become the titillating yet problematic merger of sexual and violent content into fused representation. This unexpected and proliferating sensationalism entertained the desperate, Dickensian-workhouse slave labourers—mostly children disallowed public education—a demographic that boomed during England’s Industrial Revolution. The deluge of these publications was tersely viewed by the upper echelons of British society’s intelligentsia as corrupting, vulgar, and amoral. At one point, a bill was debated in parliament to ban the reading of this material by children due to its negative impact on their productivity in the workhouses. Think of all this as an accelerationist disruption that prefigures the “highs” of Surrealism and Fluxus, and the “lows” of horror comics and exploitation cinema.

The literature-lovers of today seem largely uninformed of this crucial aspect of what I have termed elsewhere as “illiterature.” The valorisation of literature as the preeminent artform in articulately describing experience and evoking feeling is historically contextualised by its classist avoidance of cheap and obvious regalement. Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho is one of a clutch of templates that ambiguously posits a post-feudal decadence and morbidity in the privileged, wealthy, educated sophisticates—lords, dukes, barons, counts, and nobles—who wield power over the innocent and the vulnerable, usually a maiden, an orphan, a servant girl, or a distant relative. The settings are remote, isolated, and secretive. These scenarios reflect what would, by the Victorian era, become clichés of ivory tower aestheticism. Contemporary art is full of Highly Sensitive Persons (artists and curators alike) who performatively champion all sorts of abject crud in the gallery space, but outside of it in reality don’t like fluorescent lights, ugly furniture, messy AV-cabling, and aggressive noise music.

Detail of Lewis Gittus, A Swarming of Points, 2026, ten-channel audio and single-channel video, 25 minutes and 20 seconds, Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

The noise of A Swarming of Points was comparatively muted, mainly because it traded in the type of dark, carnivalesque sonics which originated in millennial Play Station 1 video-game sound designs such as Human Entertainment’s Clock Tower (1996), Capcom’s Biohazard (1996), Team Silent’s Silent Hill (1998) and Square’s Parasite Eve (1998). Their dark acousmatic configurations were brutish affairs technically due to the processing restrictions of interactive gameplay. Aesthetically, they arose from Japanese sound-designers echoing and stylising the pseudo-cinematic sounds of first-wave British Industrial bands (Throbbing Gristle, Coil, Einstürzende Neubauten, SPK, Test Dept). Those bands collectively posed anti-fascist politics as if they were on some do-or-die battlefield of art. The PS1 narratives theatricalised their tawdry angst, suffering, and terror—all in the name of interactive entertainment. Note that while this was happening, Goth music was posturing similarly in nightclubs, but without the turgid self-importance that believing one’s critique of fascism was vital to the world’s existence. I’m being harsh, but—please—every sci-fi/horror movie (mainstream and indie) scaring audiences today with future dread replicates these spooky “sonicons” of darkness: throbbing pulses, droning bass, extended reverb clangs, searing noise, low cellos, distant sirens, etc. (Don’t get me started on the pretentions of so-called “intelligent horror.”)

Thankfully, A Swarming of Points did not go down that path even if it replicated some of those tropes. If Gittus’s The Mysteries of Udolpho led us back to the powerful degradation inherent in the morbid populism of the Gothic literary-production industry, then A Swarming of Points similarly pivoted away from the portentous “serious theme” poetics of today’s dark film scores. In doing so, the latter faced both the abject pleasures of club music “bassdom” and how the history of dance music embraced noise to intensify its pleasure principles. Mostly, the strength of A Swarming of Points came from its avoidance of burping more than it could chew; its layering and mixage felt attuned to the nuances of electro-acoustic composition, especially the surface preoccupations of Bernard Parmegiani. This focus allowed the work to properly function per Gittus’s project: to configure the gallery space as a bodily containment of Gothic tactility. Resonant Entrails appropriately fused its two exhibited works, combining luridly decrepit poetics on yellowing pages with ghostly auras invisibly haunting one’s occupancy of the dark.

Philip Brophy writes on art among other things.