Daniel Boyd: Treasure Island

Matt Poll

Contemporary Aboriginal art is today the most proactive form of protesting the sacred stories that Australia tells itself about its past. Daniel Boyd has for almost two decades been a central figure in this movement. Through painting, integrated architectural interventions, screen-based and projected media, Boyd has performed a distinctive declaration of cultural autonomy against dominant narratives of historical authority. His body of work, surveyed across eighty pieces in the AGNSW’s current exhibition Treasure Island, stands as an important wayfinding point for navigating the profound shift over the past few decades in the way Indigenous life and knowledge in Australia is represented, and by whom.

Museums have been instrumental in scientifically and politically constructing stereotypical and inauthentic interpretations of the lived experience, ceremonial life, object-production knowledges and artistic craftsmanship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island peoples. Australian museums have authored versions of the past that have denied contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people the pathways to knowledges they need to exercise authority within their communities.

Boyd questions the legacy of historical, anthropological, and ethnographic representations of Aboriginal culture and their continued circulation in the world’s museums, galleries and libraries, as well as in the popular imaginary. His work is not simply a decolonisation, but more so a defamation of these representations. In his work, Boyd challenges the visual hegemony of the non-Indigenous authored version of Indigenous past. Solo exhibitions such as Treasure Island are part of a correction taking place in Australian museums and galleries which shift the viewpoint to a far more accurate contemporary experience of Indigenous life authored by Indigenous people themselves.

LENSES

The exhibition, co-curated by Isobel Parker Philip and Erin Vink, begins with a darkened entrance. The show is then broken into four thematic periods of the artist’s work, demarcated through bold colour on the walls of each exhibition space.

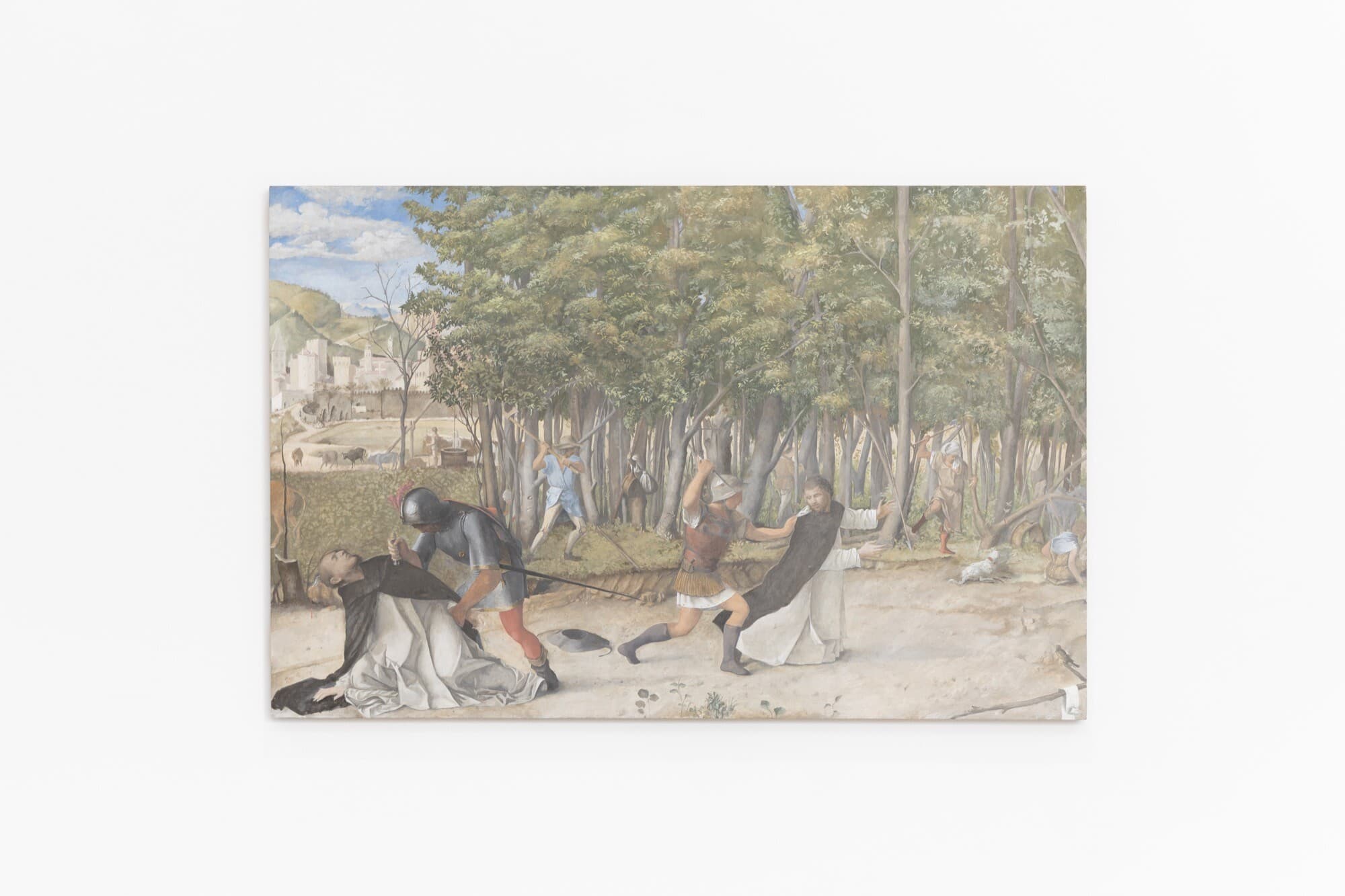

The first room includes some of Boyd’s earliest paintings, where he first experimented with covering his paintings with a layer of translucent dots. Through this distinctive method he creates an exploded surface, its content refracted through a multitude of tiny lenses. These lenses, almost like eyes, stare back at the monolithic era when museums were machines of extractive capitalism.

For many indigenous people, fragments of objects and pieces of historical information in museums or archives are the starting point in a lifelong journey of deciphering the way that the colonial apparatus has obscured their history. The Australian national story told and conserved by Australian arts institutions often obscures the active role that these same institutions played in this apparatus, transforming the diversity of Indigenous botanical, animal and human life into catalogues, menageries and commodities.

The truly innovative approach that Boyd adopts, and which makes his work so compelling, is a forced redirection of this perspective. By extracting images of Indigenous life from museum archives and layering them with his lenses, Boyd makes their content harder to perceive by the colonial gaze, and refracts it in a thousand different directions.

TREASURE ISLAND

The exhibition’s title derives from Boyd’s first body of work, which gained prominence after 2005. Treasure Island brings together significant works from this period, which challenge contemporary Australia’s foundational moment.

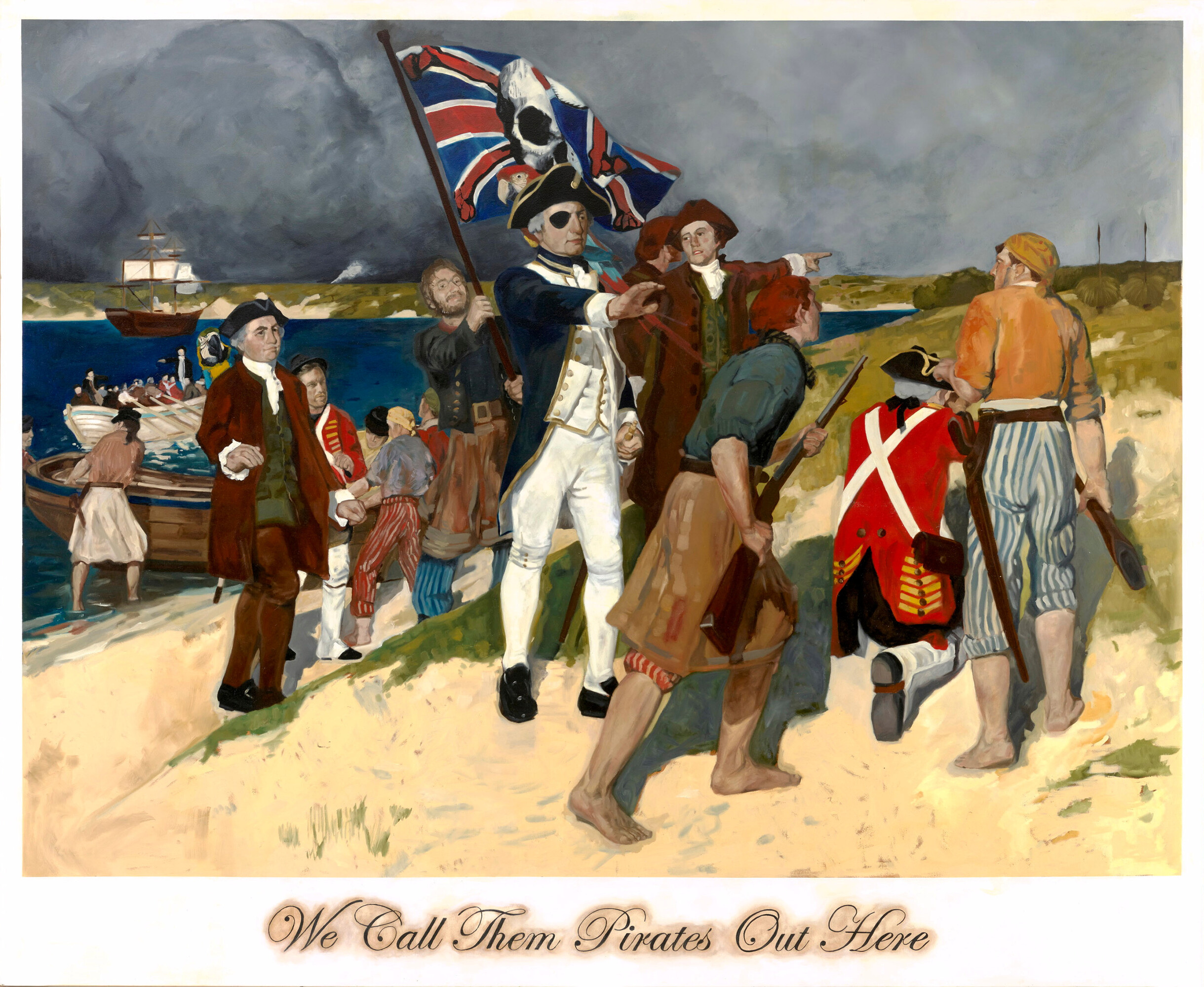

Australia’s colonisation by the British Empire and its attempt to overshadow Indigenous worlds, knowledges and experience has not gone unchallenged by generations of many different Indigenous nations across Australia. Boyd represents the latest in a long line of activist retellings of the moment of colonial encounter. Boyd’s reimagining of Emanuel Phillip Fox’s grand painting of Cook’s landing (We Call Them Pirates Out Here (2006)) becomes a reconstructed assemblage of contemporary viewpoints of alternative Indigenous perspectives. The connection to Cook is not random: the artists grandmother’s Country is located near where the Endeavour ran aground in 1770. It is a challenge being taken up by all First Nations artists when choosing to engage with museums as to how comfortable they feel in inserting their own presence and experience into these collections, objects and archives. Boyd offers a powerful example of how best to navigate this through his work.

The scale of Boyd’s paintings, and their presentation in exhibitions in places such as the Art Gallery of NSW, mimic the canonical art historical tradition that he engages with. But his subject matter, and the deeper structural racism that his work exposes, mean that his work offer not only a pointed rejection of tradition but an alternative process whereby Indigenous agency is foremost in historical representation.

IMAGES/OBJECTS

First Nations objects and representations of their culture have in the past existed in a form of indentured servitude to the colonial state, their purpose throughout their lives being to reinforce cultural hierarchies and tantalise those with a passion for the exotic and unseen. Boyd liberates historical imagery of Indigenous culture from its role as evidence of the past, reworking it into a dynamic and expressive platform for truth telling, authored through Indigenous agency itself. One of the powerful demonstrations of this from the exhibition is Sir No Beard (2007). The terrorism inflicted on Sydney’s Eora people by colonisation which is casually masked as Joseph Banks’s “curiosity” for native peoples warranted reportage in the English press. In 1802, the Bury and Norwich Post published a newspaper article of the surprising collections arriving from the new colony of Port Jackson:

A curious circumstance occurred in the gauging of a cask taken from on board the speedy (South Whaler), from Botany Bay, on the custom-house Quay. The exciseman, as is usual, wishing to ascertain the contents, put the instrument in… when, to his great surprise, he found the head of one of the natives of Port Jackson, for which a reward of five guineas had been advertised… on investigation, it proved to be a present from Governor King to Sir Joseph Banks.

In Boyd’s appropriated and repurposed portrait of Banks, the artist masterfully disempowers the heroic portrait of Banks painted by Benjamin West in 1771 Portrait of Sir Joseph Banks, which shows Banks surrounded by the treasures from Cooks first expedition. Boyd reinserts his own face into that of the dismembered Pemulwuy staring back up at Banks almost with an expression of questioning.

Boyd’s work asserts that these objects are ancestors for First Nations people and, sadly for many, these objects and collections remain the only tangible link with the cultural lineage of their ancestors who were so violently dispossessed. One of the greatest challenges facing First Nations people today is to reassemble these dispersed objects, and thus enliven a new material foundation for an Indigenous-authored past and future.

Where First Nations peoples’ tangible and intangible intellectual and cultural properties have become assets of cultural institutions, accounts of First Nations peoples’ involvement in these networks of collections histories have largely been relegated to being assistants to the collectors, curators, and anthropologists rather than performing these roles themselves. Boyd often singles out these actors of historical agency, magnifying but also obscuring their comprehension. His painting methodology refuses the ready access and availability of the source material Boyd uses.

KIN

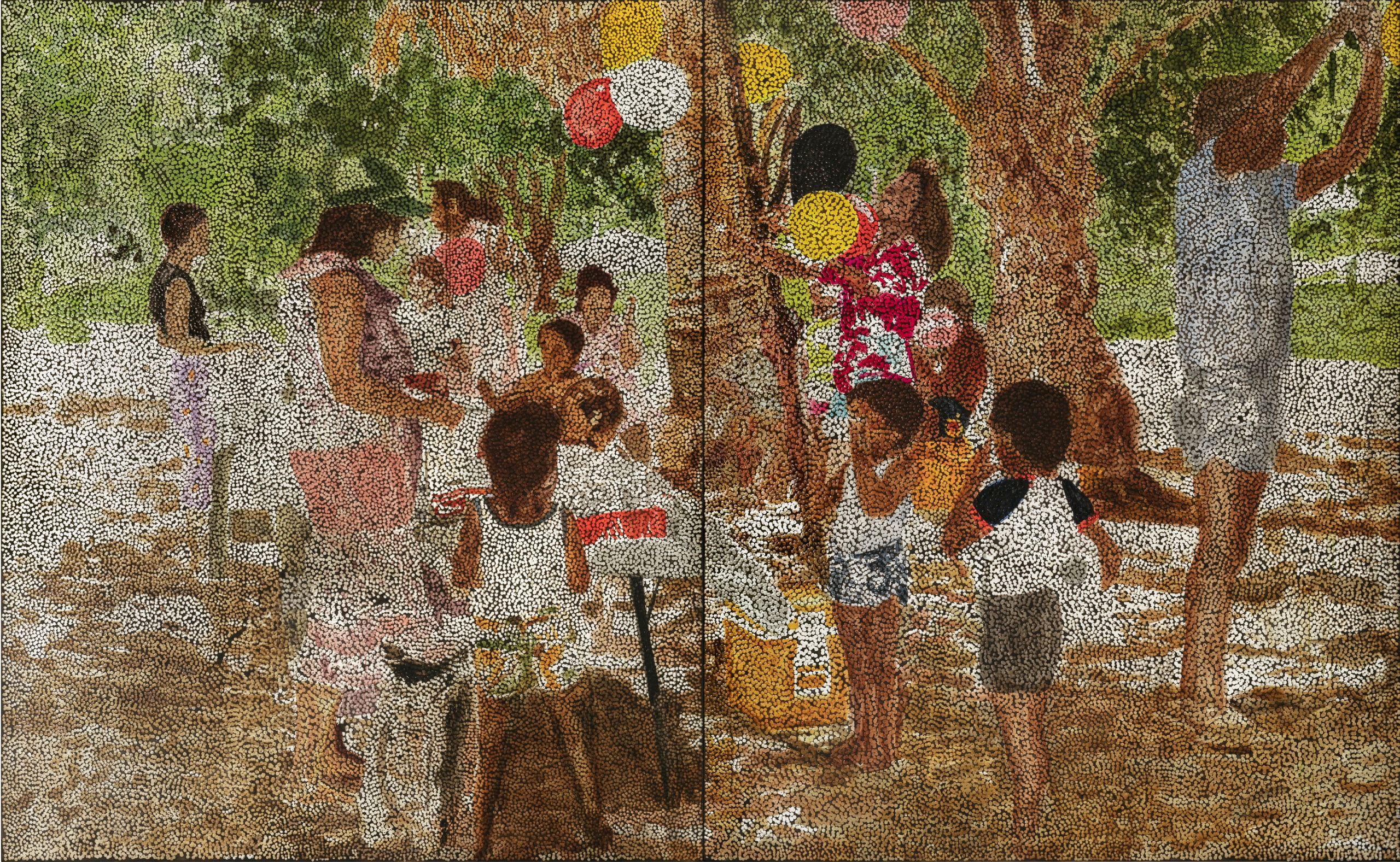

The methodological research evident in the exhibition Treasure Island is not simply a reinvention of the past. Boyd addresses the very real danger of treating the past as if it was terra nullius (nobody’s land) through the inclusion of works using images of his own family members. Boyd operates through a process of Indigenising the past, which involves bypassing the colonially authored past and privileging First Nations’ authorship of the historical record, using methodologies that empower First Nations people, but that also recognise the structural inequalities and hierarchies of privilege that permeate historical information.

Kinship is integral to understanding the diversity of nations across First Nations Australia. Boyd successfully obscures access to the non-Indigenous authored versions of these stories through naming each of the works Untitled …, but also adds playful clues to where his source material is drawn from with the use of initials, numbers and archival research codes, hinting to sources of information he is overturning.

In a report commissioned by Museums Australia, the 1986 National inventory of Aboriginal artefacts, a little over one hundred thousand Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander objects were identified as being held across twenty-four collecting institutions in Australia. The production of contemporary Aboriginal art since 1986, four years after Boyd was born, is also an exponential counter-archive authored by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island artists such as Boyd which authoritatively declares a far more authentic and accurate assertion of an Aboriginal and Torre Strait Island future.

The forensic or scientific frameworks through which a particular version Aboriginal culture was made visible to non-Indigenous audiences, especially throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, offers little for many in the contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island community to use as representational models for depicting their culture.

Incorrect and non-authentic histories authored by non-Indigenous agency, when repurposed by contemporary Aboriginal people into versions of their culture, can run the risk of legitimising the very structures of oppressive and offensive cultural representation from which they are drawn. The challenge which Boyd rises to meet is to otherise the concept of othering Indigenous people themselves, not through reclamation of culture depicted in fraught historical source material but by undermining the bedrock of historical representation itself. In Treasure Island, Boyd offers an important challenge to Indigenous artists, researchers, and historians to not treat the Indigenous past as terra nullius, or treasure island, but to use their personal story as an entry point to the networks of power and authority that they seek to overturn.

Matt Poll is a curator and writer based in Sydney.