None of Us Are Free / When One of Us Is Chained

In a recent media release from the office of the Minister for the Arts, Tony Burke (2024) referred to a government arts initiative as an “opportunity to highlight exceptional but lesser-known works within the National Collection and share them with communities for whom they hold special significance.” Imagine: $11.8 million over four years spent on transferring and safeguarding old paintings like The Countrywoman (1946) by Russell Drysdale and The Anteroom (1963) by Charles Blackman. The two old ghosts from the graveyard return to the gentlemen’s estate at Retford Park for the bourgeoisie of Bowral. Are you bored yet? You bloody well should be.

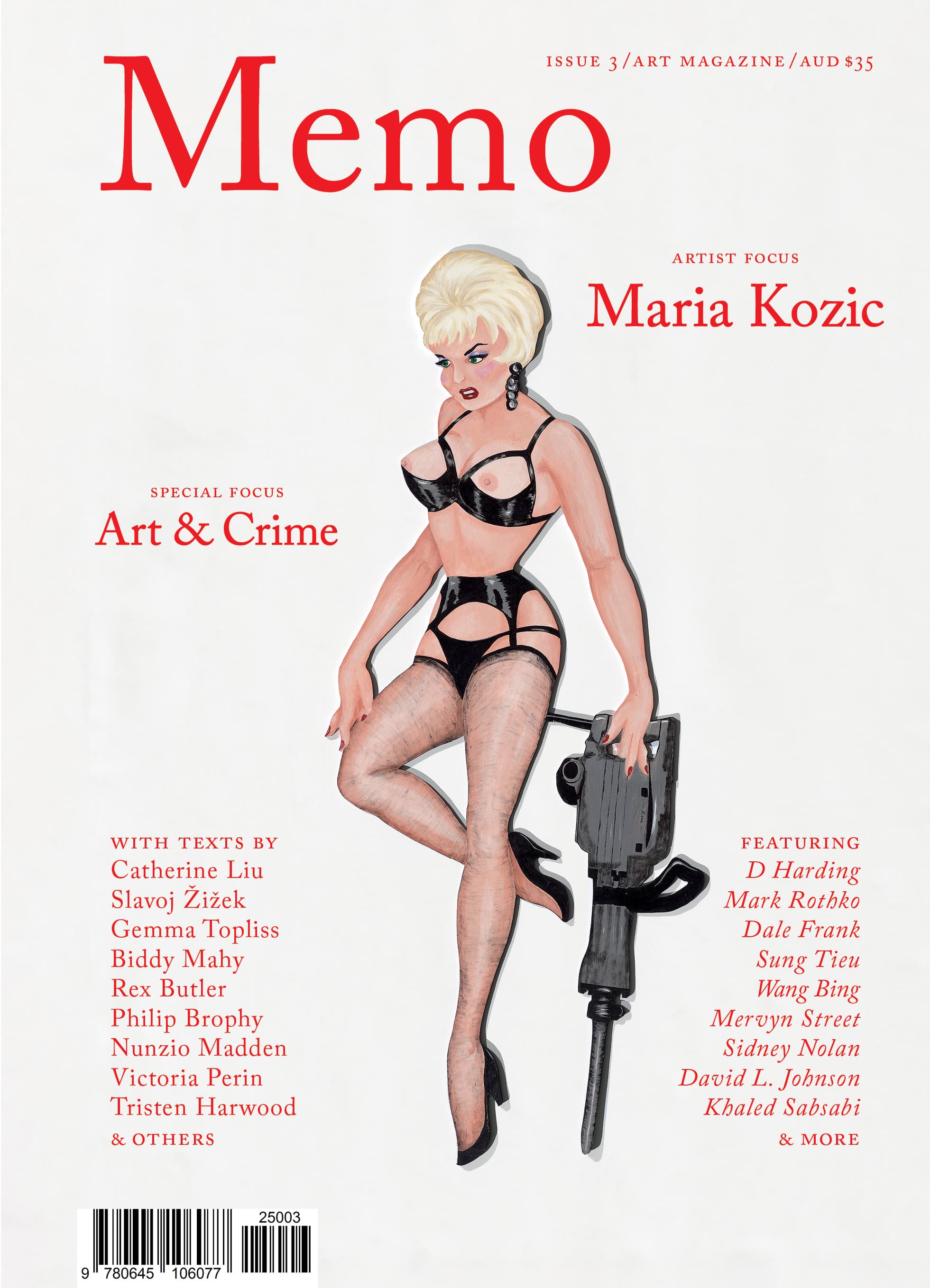

Exclusive to the Magazine

None of Us Are Free / When One of Us Is Chained by Daisy is featured in full in Issue 3 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.