Warraba Weatherall, Shadow and Substance, 2025, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, © the artist, photograph: Jessica Maurer

Shadow and Substance

Lachlan Thompson

Sometimes, art speaks to you. This can mean two different things. On the one hand, it most commonly means that the work affects you; you feel something because of it. On the other hand, the phrase evokes the action of the work itself; it addresses you. Shadow and Substance, the first institutional solo show by Kamilaroi artist Warraba Weatherall, spoke to me in both these senses—and indeed, works strategically in the space between them.

Shadow and Substance is a succinct show. It comprises six works, surveying eight years of Weatherall’s practice. Curated by Megan Robson, each work within the show comes from its own respective body of work and, while they are thematically linked, each demands close attention. It is a therefore also a dense show, thick with research..

Research is, in fact, at the core of Weatherall’s work, as well as the context he works within—he is both a convenor for Griffith University’s Bachelor of Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art, and a PhD candidate himself. It makes sense, in the first instance, to think of his work through the frame of “research-based art.” As most influentially defined by art historian Claire Bishop, research-based art is a phenomenon that has risen to prominence since 1990s and is linked to the uptick in Fine Arts post-grad and PhD programs. Aesthetically, it can be considered through the methods and practices artists use to reconfigure information into an artwork.

Warraba Weatherall, To know and possess, 2021-2025, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2025, cast bronze, 30 parts: parts 1-10: Purchased 2022. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation, Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, part 11: Private Collection, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, photograph: Jessica Maurer

Yet this framework of research-based art does not tell us the full story of Weatherall’s practice. As has been pointed out by Callum McGrath, Bishop’s definition is built upon an analysis of practices that primarily stay within the formal tropes of Western knowledge production. Weatherall’s show is an instance where First Nations art practices exceed and trouble genres such as Bishop’s. This is exemplified by the way Shadow and Substance operates within the gallery—it speaks to its audience.

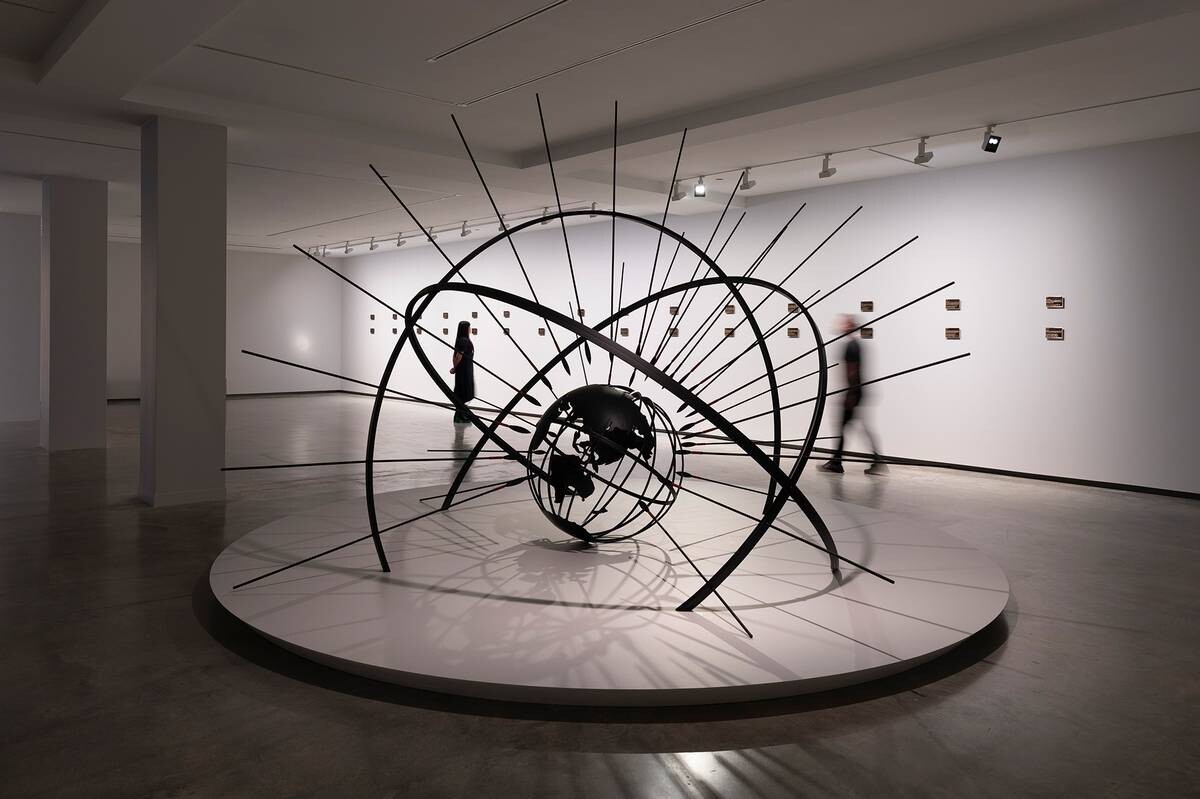

InstitutionaLies (2017/2025) is one of the most striking works in the show. It was devised as a public monument to commemorate thirty years since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, during which time over six hundred Indigenous Australians have died while in the supposed care of Australia’s carceral institutions. The sculpture is a black steel craniometer—a device used by phrenologists and eugenicists to measure the size and shape of people’s heads. Weatherall’s version appears on a massive scale, and its measuring pins have been replaced with spears. At the centre of the machine is not an individual’s head, but a globe.

Weatherall’s revision of the craniometer prompts two readings. The first is a transhistorical statement. In an interview with Daniel Browning, Weatherall states that the impetus for the work was research into the photographic mug shot, which was developed in the late nineteenth century as a tool of policing and incarceration, and of phrenology—to classify “vagrant” or “deviant” individuals. In this transhistorical configuration, a device of colonial knowledge production becomes entangled with the long tail of its own legacy: eugenics and the continuing hyper-incarceration of First Nations peoples.

The second reading emerges when we turn our attention to the spears. In the operation of the craniometer, the measuring pins are positions from which measurements are discerned and taken. In shifting the scale of the device, by which it encloses a Western vision of the world (the globe), and replacing the measuring pins with spears, Weatherall iterates a mechanism of colonial violence into an image of Indigenous resistance. The image depicts a Western vision of the world, surrounded by Indigeneity.

Warraba Weatherall, front to back: InstitutionaLies, 2017/2025, and To know and possess, 2021–2025, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2025, To know and possess: parts 1-10: Purchased 2022. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation, Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, part 11: Private Collection, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, photograph: Jessica Maurer

It is an astute and staunch statement that Indigeneity exceeds the confines of any material, epistemic, ideological or historical structure imposed by invasion. InstitutionaLies illustrates a point made by theorists Fred Moten and Stefano Harney: a critique of colonial violence must affirm the life that came before it. The colony was, and is always, surrounded by the Indigenous life that preceded it.

Working in Meanjin/Brisbane, Weatherall is at the heart of an amazingly vibrant, multi-generational community of First Nations contemporary artists. He is part of the artist collective proppaNOW, and is represented by Milani Gallery alongside Richard Bell, Judy Watson, Robert Andrew, Gordon Hookey, Vernon Ah Kee and Megan Cope. He is thus working with and alongside some of the most prominent Indigenous Australian contemporary artists in Australia today.

In Weatherall’s biting critiques of colonial Australia, we can certainly see the influence of figures like Bell. In his 2021 exhibition You Can Go Now (the most recent solo show by an Indigenous Australian artist at the MCA, curated by Clothilde Bullen) Bell’s work boldly transformed the space of the gallery into a space of protest. His large scale paintings, taking cues from the protest sign and placard, directly address a white settler public: “YOU COME FROM HERE” superimposed on a map of Europe; “PAY THE RENT”; or simply, as a sign leant against a pole of Bell’s famous Embassy (2013–) states: “WHITE INVADERS/YOU ARE LIVING ON/STOLEN LAND”. In congruence with Bell are Gordon Hookey’s banner paintings: one depicting an Aboriginal flag with the sun replaced with a yellow fist, in reference to Black Power; or another, stating in large black text, “Houses are/homes,/NOT!/inve\$✞men✞”.

Warraba Weatherall, Trace, 2025, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2025, wood, aluminium, paint, co-commissioned by MCA Australia and Hawai’i Contemporary, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, photograph: Jessica Maurer

Protest is also part of Weatherall’s own family and history. His father Bob Weatherall has been instrumental in continuing efforts to repatriate stolen ancestral remains and cultural materials. Weatherall’s work, like that of his father, and his Brisbane comrades Hookey and Bell, makes an active address to a settler public. It is significant that InstitutionaLies was first envisaged as a public artwork, as was another work in the show, Single File (2019/2025). Weatherall’s work, like that of his proppaNOW colleagues, speaks to its audience—it makes a demand.

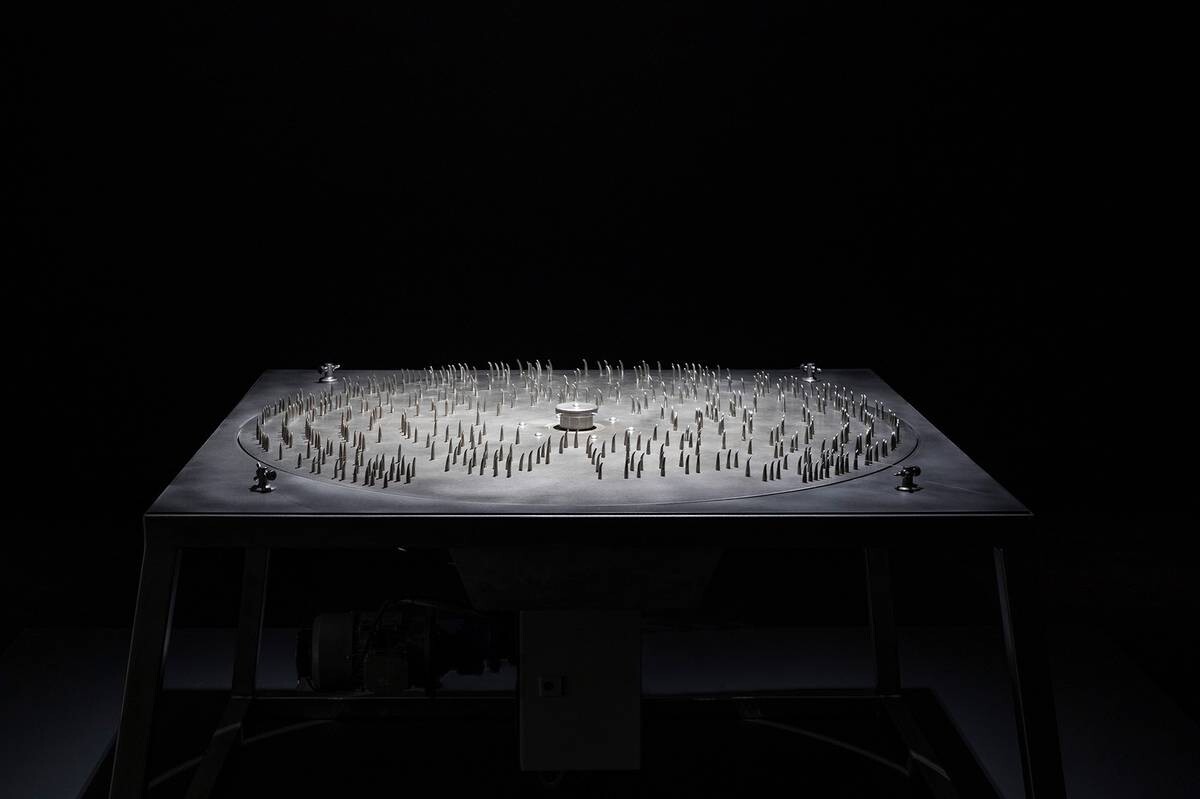

A work that explicitly draws on Weatherall’s family history is Trace (2025). When researching his own family history, Weatherall came across the work of American eugenicist Charles Davenport. In the early twentieth century Davenport undertook studies to measure the colour of Weatherall’s relatives’ skin, using as his aid an altered version of Milton Bradley’s iconic spinning top, with colour swatches attached. For his work, Weatherall has reproduced the spinning top at scale, carving Kamilaroi funeral patterns into the blackened wood.

Trace extends to the adjacent wall as a grid of aluminium panels, each coated in a different colour referencing Paul Broca’s skin colour chart. However, the colour fixed to these panels has been carved away in a spiralling pattern. The movement of the spinning top itself reveals fragments of Davenport’s scientific paper detailing the eugenic measurements of Weatherall’s relatives.

Warraba Weatherall, Dirge, 2023, installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2025, steel, aluminium, motor, electrical components, sound, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, purchased with funds donated by Country Road for the Country Road + NGV First Nations Commissions, 2024, image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia © the artist, photograph: Jessica Maurer

Heard from the main gallery space is Dirge (2023), a large aluminium music box, or polyphon, which plays a haunting tune in which a document relating to Aboriginal land rights has been translated into braille and then into a large polyphon disc. The document is played as a mourning song. As an act of translation, the colonial document speaks to us anew as something that is heard, but also felt.

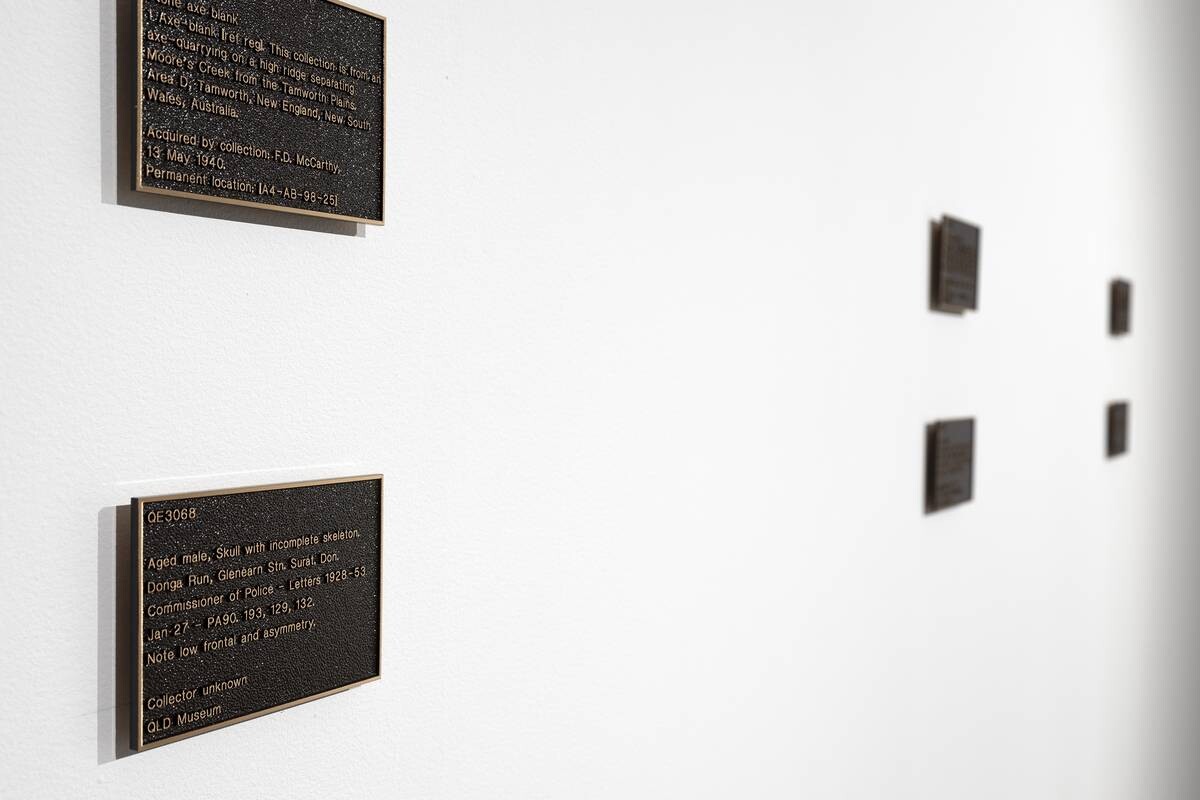

The least physically imposing, yet most damning work in the show is an extract from Weatherall’s series To know and possess (2021–25). The gallery wall is lined with museum collection index cards of stolen Kamilaroi artefacts and ancestral remains—these have been cast in bronze, as if memorial plaques in a crematorium, a war memorial, or simply a label for a statue. Lifted directly from archives and institutional websites such as the Queensland University Museum, Weatherall places in clear, public view the culturally significant objects and human remains which are still held by institutions.

Warraba Weatherall, To know and possess (detail), 2021–2025, bronze cast, image courtesy and © the artist

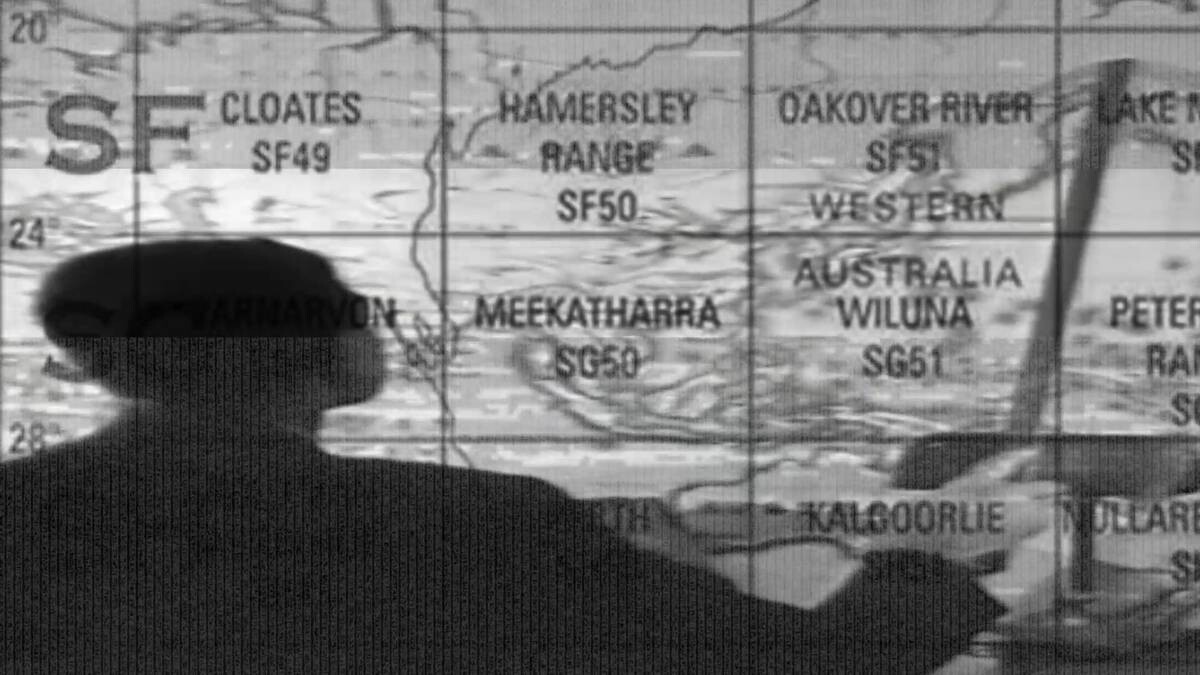

Weatherall has done his research, and names names. The work discloses not only the present location of these stolen artefacts but, importantly, the eugenicists who desecrated people’s bodies and donated them to museums, the police officers who stole cultural artefacts and anthropologists who destroyed cultural sites. There are numerous plaques, for example, describing “modified trees” or scar trees, donated by anthropologist Lindsay Black. (Black is further exposed in another work in the show—the two-channel video work, Dialectic (2025), which shows him and Norman Tindale felling scar trees.)

Weatherall’s plaques foreground how the language of the museum places a thin veil of methodological distance between the institutionalised object and the act of violence and theft that captured it. But there are instances of this veil tearing. As one of the most poignant plaques in the series reads:

E063792

Shield, 53.5x27.7\

One piece wooden shield, oval. Both ends rounded. Cross—section, planoconvex. Handle carved from the solid, flush with surface. Black and red ochre anterior surface. Condition: complete. Well worn, pitted, ochre nearly all cracked off. Shield; left by Aboriginies after Myall Creek massacre—notice shot holes.Area D, Myall Creek, Bingara, Australia.\

Acquired by unknown: C.J. McMaster, 05 Dec 1968.\

Permanent location: (A3–05–01–10)\

Building A – Floor: 3–05

The index card and object are remnants of one of the most violent recorded frontier massacres in Australian history and have been tempered with museological and archival rhetoric. However, in the final line, the index card breaks into a separate clause “—notice shot holes”. Here, the plaque instructs the reader in a particular way to view and know the shield. This is what runs beneath colonial archival logics: instructions which impose specific ways of seeing and knowing or, as Weatherall puts it, techniques for “disciplining” cultural knowledge.

The demand that runs through Shadow and Substance is clear and specific: the museum and the academy must acknowledge the complicity of colonial epistemic practices in the continuing violence of the colony. In works such as To know and possess, this extends to nothing less than a call for the complete repatriation of ancestral remains and cultural materials. Weatherall continually directs this towards a settler audience and the institutions themselves.

Warraba Weatherall, Dialectic, 2025, still, detail, work in progress, 2-channel digital video, sound, videography and editing: Joshua Maguire, sound design: Samuel Pankhurst, image courtesy and © the artist

Weatherall’s exhibition demonstrates a subtle synthesis of the legacies of protest and public art, with the characteristics of contemporary research-based art. As in the work of Bell, whose work not that long ago graced the same site, Weatherall uses the white walls of the gallery space to stage a protest—to both critique the history of Australian settler-colonialism, and make a powerful assertion of Indigenous sovereignty. For Bell, the site key site for this protest is the word. His work, channelling the work of street chants and placards, reworks English into witty, powerful slogans: “THOU SHALT/HAVE BUT/ONE HOUSE”, “LEAVE/US KIDS/ALONE”, “WE/WERE/HERE/FIRST”. Weatherall, on the other hand, works with not so much the language of settler colonialism, but its tools, gadgets and gizmos: the spinning top, the dialectic (itself, a tool of the academy), the administrative document, the index card, the filing cabinet. All these tools are not static historical artefacts, but further the colonial project in our present. Weatherall’s intervention is to revise these objects such that they index their own complicity within the totalising violence of the colony. Complicities are brought out of ambiguity and placed in the view of a settler public.

Weatherall’s upward trajectory is one to follow. As his audience inevitably expands, or his practice goes global (following the path of Bell or Archie Moore), the genre of artist-as-researcher may become a way his practice is made legible to an international audience. Such a classification, however, runs the risk of glossing over the localised and situated demands that precede and motivate Weatherall’s practices. Shadow and Substance stands as a reminder of the inseparability of these demands and their implicit material presence in the world, a demand from within the gallery, a painted banner, a song of mourning, a public monument, a direct address to the colony.

Lachlan Thompson is an artist and writer based on Cammeraygal and Gadigal land.