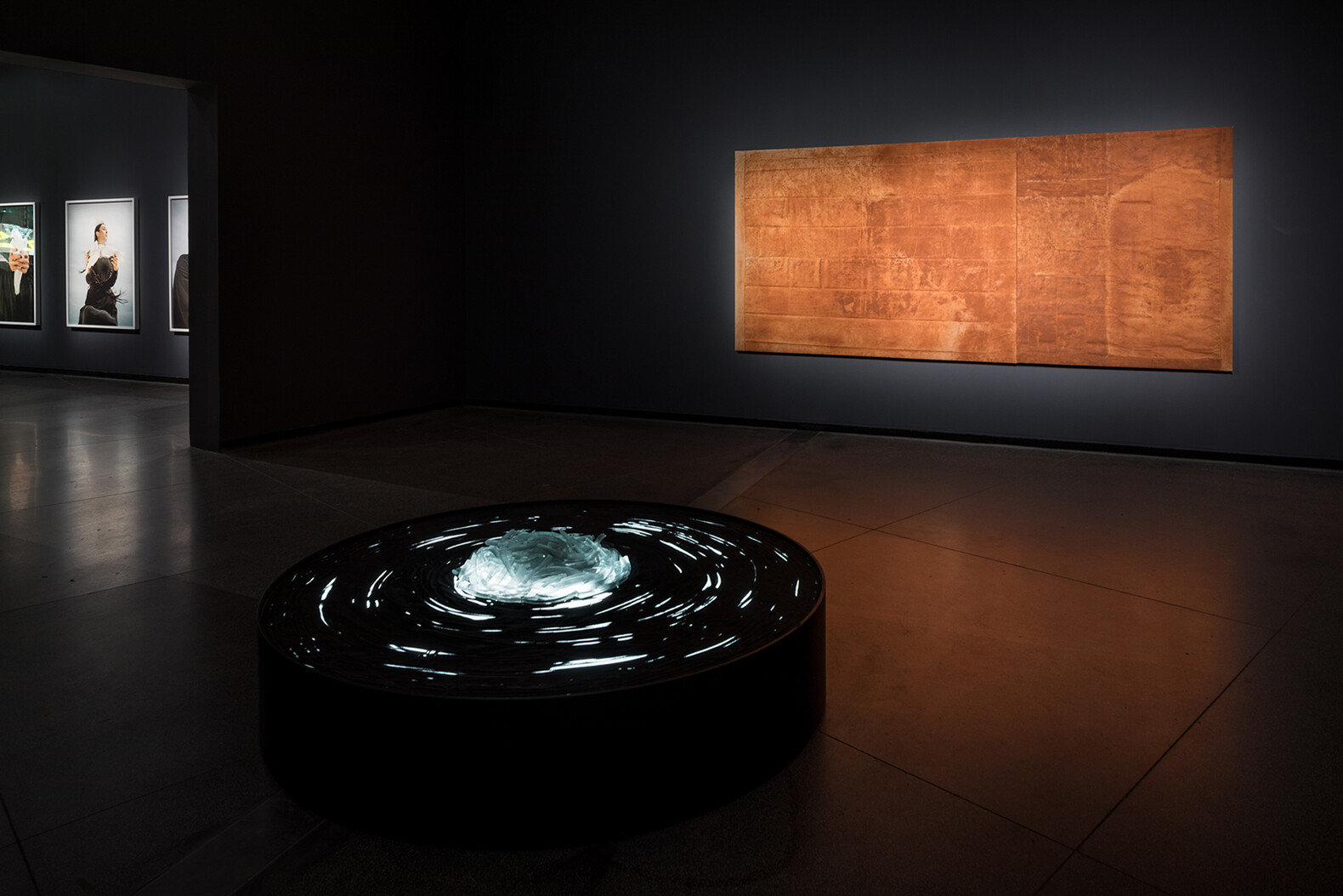

Installation view of Five Acts of Love, 2025, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis

Five Acts of Love

Aziz Sohail

How else can one review Five Acts of Love, except through and with love itself? As I write this, I recognise, suddenly, one of the meanings of my name, Aziz, a word in Arabic, Urdu, Persian that means “the loved one.”

To enter this exhibition curated by Dr Nur Shkembi OAM at ACCA on a cold winter afternoon in Naarm is to enter with this feeling of love, and to witness with care. On my first visit, I carry many emotions with me—feelings of trepidation, curiosity, hope, and desire. Five Acts of Love could not have come at a more opportune time in many of our life cycles. That is, in a time of acute and intense sadness, when our marginalised identities are increasingly caught up in the political agendas of major Western powers. Indeed, I write this review with my positionality as a queer, Muslim, migrant writer, also “from a place of grief,” as Shkembi writes in the exhibition catalogue. The exhibition then feels like a generous gift—a Hadiya, to borrow the Arabic phrase—for those who may spend time with it. While many are rightly angry and furious in this time of injustice, this exhibition exudes a quiet power through its refusal of forces that seek to divide, destroy, and render us helpless, instead offering as Shkembi notes “only one place to return to: love’,” as an antidote, as a balm, as a space of healing, and one of resistance and revolt. I admit, I initially had trepidation, given the gesture to the Rumi, a thirteenth-century Sufi poet from whose writing and thinking this exhibition is developed. I am mindful of the critique that has been leveraged by many scholars on how Islam and its spiritual layers have been removed from his writings in favour of a new age secular spirituality—a superficial borrowing. This is also seen in many exhibitions and practices—especially, of many diasporic, Muslim, migrant and brown artists exhibited in the settler colonies, where their work is categorised through identity, rather than content or affect.

Installation view of Five Acts of Love, 2025, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis

However, by bringing her own embodied experience to the role of curator, Shkembi refuses these binary and superficial subjectivities, offering a more complex and layered engagement with her chosen artists. Scholars like the Bangladeshi-Australian Samia Khatun have long reminded us in texts like Australianama of the ongoing and long connections between Indigenous and Muslim/South Asian/Middle Eastern migrants on this continent, urging us to re-imagine the relations and history here, rather than one of just the dominant story of white colonisation and erasure of other voices. Five Acts of Love centers on these two identities, around which ideas of “resistance, revolution, intimacy, memory and annihilation (fanaa)” circle. Indeed, the exhibition centres the circle and its infinite sacred—a reminder again from Rumi and from Shkembi that “the lover circles his own heart.”

What circling could we speak about here? There is of course a continuity, an ebb and flow, but also rupture. A key work is by the late Hossein Valamanesh (1949-2022), an Iranian-Australian artist who was based in Adelaide and who was a mentor to many younger artists, but whose legacy is yet to be more properly understood. A key work of his, The lover circles his own heart (1993), consisting of “a sheet of white silk that rotates in a circular motion” refers to the whirling dervishes, here abstracted and universalised to represent infinite, quiet movement, connecting heavens and earth, time and space. This work could be considered the nucleus from which the rest of the exhibition flows.

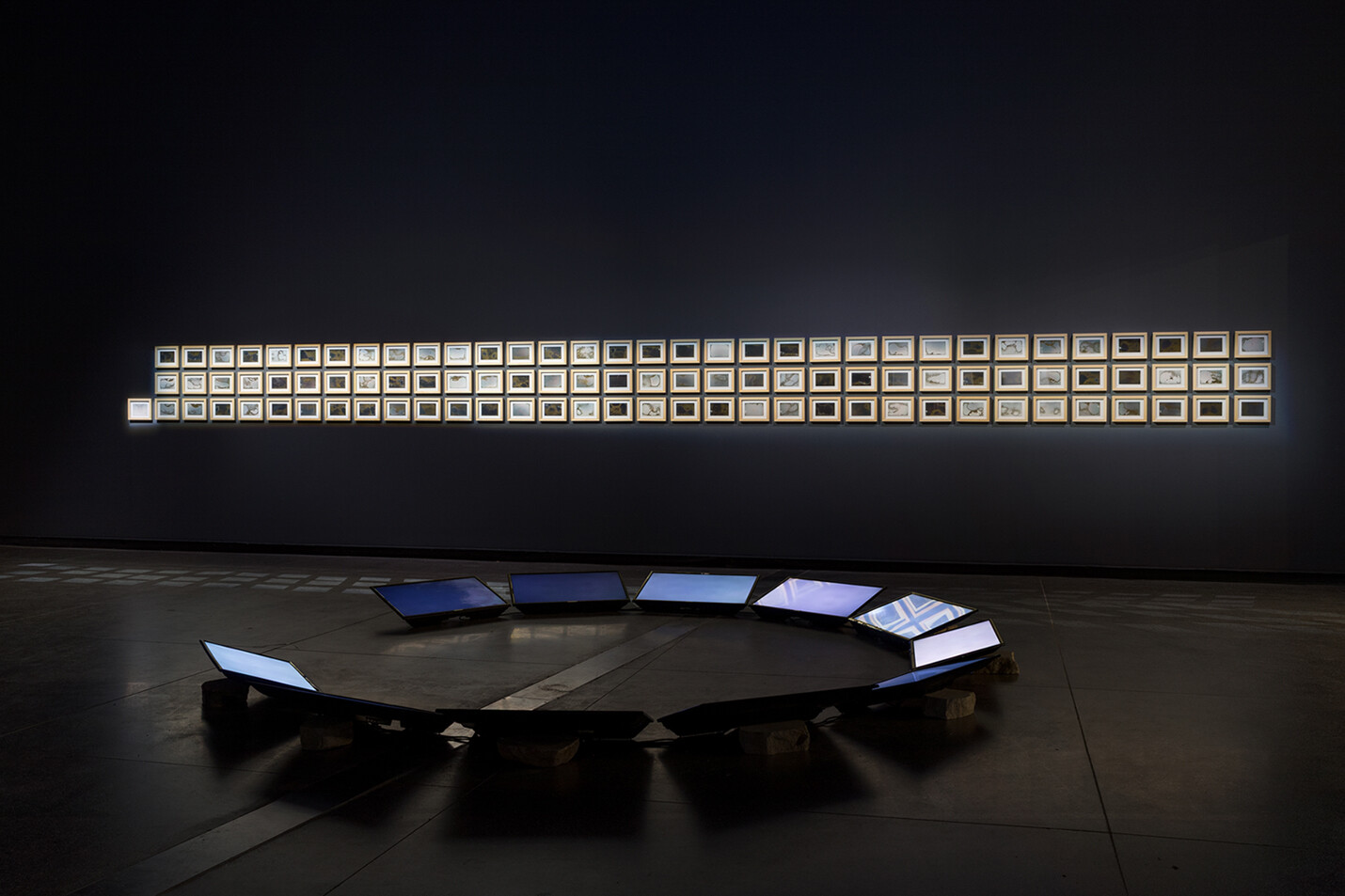

Engaging with the exhibition necessitates an acknowledgement of the elephant in the room. That is, the recent and ongoing controversy around Khaled Sabsabi’s practice, and its unjust manipulation to right-wing political ends. Sabsabi’s work is the first one sees upon entering the exhibition and it refuses easy categorisations or interpretation through his vast oeuvre. Here, he presents an installation At the Speed of Light (2016), consisting of eleven TV screens presented in a circle, each of which accelerates to show the speed of light—melding traditions and ideas of humans being descended from light. Nur’s name itself means light and it is hard for me not to draw a metaphorical link between her offering, in the form of this exhibition, as a light within darkness.

Installation view of Khaled Sabsabi, At the Speed of Light (2016), Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery,Meanjin/Brisbane. Photo: Andrew Curtis

There is a continued and welcome opacity throughout Five Acts of Love, which feels necessary and urgent in this time when one is asked to explain their intentions or practices, and yet is still misunderstood. As someone brought up in the Muslim tradition, there are ways I intimately relate to certain works, such as another part of the installation by Sabsabi. This part of the work is composed of one hundred works on photographic paper—99 to refer to the names of Allah, which embody all of the understandings of His sacred attributes for us in Islam, while the final one represents the unity of the One itself—a connection between sacred and profane, heavens and earth. Simultaneously, there are works that borrow from other spiritual and world traditions that I cannot fully understand or engage with. These include those by Indigenous artists D Harding and Megan Cope, whose works She Come from the low-country, he come from the high-country II (2025) and the tide waits for no one (2020-21) carry soil and land from their respective Countries, and examine their ancestral lineages with respect to colonisation, but with care and generosity. Here, these artists’ long and unbroken relationship to Country is personal and special, and not a place that those who are settlers from other lands will ever be able to fully ever understand.

A continuing thread of tenderness is evident throughout the exhibition, even in those works that face the topic of forceful violence. Ali Tahayori’s series Archive of Longing (2024-25) brings together archival photographs, which are redisplayed and cropped to produce new narratives. Tahayori is a diasporic queer artist, and this methodology becomes a way for him to reconnect his current present back to his family history, through ideas of loving and longing in the family archive, some of which may now be inaccessible to him. The photographs show quotidian and daily intimacies in family life, sometimes re-oriented or cropped to bring attention to touch, love and identity in ways that are not immediately visible. Each work is layered with glass, which from afar appears cracked. Upon closer inspection, the viewer sees that this effect has been lovingly and deliberately crafted by the artist through the technique of Āine-kāri آینه کاری (Mirror-works), a classical Iranian technique deployed here to powerful impact. The gallery lights interact with the works’ surface to produce an incandescent reflection on the gallery floor—light/Nur continues as a theme, and, to my mind, invokes the Islamic verse ‘Nur un Al Nur / light upon light’. In an adjoining room, Yhonnie Scarce’s N000, N2359, N2351, N2402 (2014), is tangentially connected to Tahayori’s work by way of the family photograph, here ensconced in fractured glass domes, as if displayed in a museum and depicting the colonisation and incarceration of Indigenous communities, as well as the looting of their personal objects. One of the only First Nations glass blowers on this continent, Scarce’s use of the medium is a response to the British nuclear tests at Maralinga in the 1950s, which transformed the sands of her Country into glass. Her utilisation of this inheritance brings resilience and survival to the fore, even under erasure.

Installation view of Ali Tahayori, Archive of Longing, 2024–25 series, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist and THISISNOFANTASY, Naarm/Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis

Connecting to the history of First Nations communities on this continent, one of the key themes in Five Acts of Love is the ongoing genocides, erasures and enclosures of the Palestinian people. Take, for example, Abdul Rahman Abdullah’s new commission Witness (2025), a sculpture of the Palestinian mountain gazelle, which is endangered, or Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind’s collaborative film Familiar Phantoms (2023), which traces the histories and memories of a childhood home in Bethlehem. Here I turn to the idea of witnessing as embodied in Islamic thought—the idea of Shahadat, which has a double meaning in Arabic, meaning to witness, but also to be a martyr. It does not escape me, the attacks upon personal freedom and erasures of humans and entire communities just for steadfastly calling attention to the violences and injustices of the last two years.

I come to Five Acts of Love not without critique. Because what exhibition is perfect, and indeed what human creation? Indeed, I am reminded of the stories in Islamic art, where the painter would always deliberately leave a mistake as an ode to only God being perfect. Similarly, while a lot of the exhibition was tight and focused, the room featuring In Turn (2023), a series of photographic works by Hoda Afshar depicting female intimacy in the wake of the uprising for women’s rights in Iran, and a film Her Right (2020) by Saodat Ismailova, bringing together archival footage and documentary to examine histories of women’s emancipation in communist Uzbekistan, both by fierce and powerful artists in their own right, seemed disconnected and perhaps required more fleshing out. It felt that more works were needed, and an engagement with more practices, so as to fully consider the intimacy between women and their struggles in the world, and place it in the context of the broader exhibition and other themes evident throughout. However, to engage with what does not make sense is also an act of love to the artists and curator, who are friends and kin, and allies on this long journey of life.

Installation view of Five Acts of Love, 2025, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis

I leave this exhibition coming back to perhaps what is the quietest and smallest work in the exhibition, a series of texts by Eugenia Flynn, for love of country (2025). Here Flynn poetically and deftly expands and compares the love of country to other forms of love–to one of countrymen, to country music, to sacred country. In Islamic and South Asian ideas of love, the final stage is annihilation (fanaa), where the human finally meets His creator. Annihilation is a moment of violence, but also of full knowledge. I am reminded so urgently as to how an insistence today on the love for nation-states, of artificial determined countries, is and has been a source of much conflict, and perhaps leading to our own demise. Flynn’s urgent reminder of other forms of love, beyond these borders, and towards one another, and to ourselves, is where we must always attempt to go, in order to save ourselves, and carry each other through the threshold.

Aziz Sohail is a Pakistani-passport holding curator & writer whose work builds interdisciplinary connections between art, history, archives, literature, theory, & biography & supports new cultural & pedagogical infrastructures. Their projects honour the power of queer and feminist collectivity, sociability and wayward encounter.