FEM-aFFINITY

Anna Parlane

The identification of common ground is essential for any group project, whether political, artistic, or both. Affinity is a baseline necessity for artistic collaboration and is also typically the primary product of group exhibitions, something that curators create or reveal.

FEM-aFFINITY at Arts Project Australia, curated by Catherine Bell, brings together the work of female artists with and without disability to explore affinities in their art. The show closes today at Arts Project’s Northcote gallery to embark on a tour of regional galleries around Victoria. Pairing seven Arts Project studio artists with seven artists from wider Victoria, FEM-aFFINITY offers a range of ways that artists’ work can be seen to be related: from collaborative artmaking to formal resemblance made evident through curatorial juxtaposition. While waving the banner of intersectional feminism, the exhibition resurrects a number of the themes and strategies deployed by feminists in the 1970s and achieves similarly mixed results.

The show addresses feminism’s intersection with the practices of artists with disability. The point of overlap is primarily in an ethic of advocacy for groups of artists who have been systematically marginalised by a society that doesn’t take their needs or perspectives into account. It promises, implicitly, to help redress the double marginalisation of female artists with disability by not only showcasing their work but also demonstrating the shared interests and experiences that link them to their able-bodied and neuro-normative peers. This goes to the heart of Arts Project’s enterprise: the studio and gallery originated in 1974 as a series of exhibitions organised by Myra Hilgendorf around the work of her intellectually disabled daughter Johanna. Hilgendorf, who also had ties to the Women’s Art Register which formed in 1975, argued that artists with disability should be afforded the same dignity and professional opportunities as any other artist. Hilgendorf’s activism aligns with Linda Nochlin’s analysis in her classic 1971 essay, “Why have there been no great women artists?” Nochlin identified the unspoken power disparities and inbuilt disadvantages that have historically prevented female artists from achieving the level of artworld prestige available to their male counterparts. The practical advocacy Arts Project performs for their studio artists, similarly, aims to mitigate the structural disadvantages artists with disability have faced when navigating the art world.

The fact that these political concerns are still relevant is evident—paradoxically enough—in Arts Project’s success. Enabled by the tailored support of such studios, a number of contemporary artists with disability have achieved unprecedented art world visibility. The fact that the political concerns motivating the formation of the Women’s Art Register are also still relevant, however, is evident in the fact that the biggest names to emerge from Arts Project are almost all men: Julian Martin, Alan Constable, Terry Williams. In this respect, Bell’s focus on the studio’s female artists is very welcome.

The exhibition’s star collaborators are Eden Menta and Janelle Low, whose witty photographs play with the well-established feminist traditions of costuming, self-portraiture and performance. The two clearly had a lot of fun together, as their truly splendid photograph Eden and the Gorge (2019) demonstrates, and could easily sustain a show just of their own collaborative work. While Menta’s humour and her considerable agency as a performer come through clearly, I would have liked to see the photographer and model roles in this collaboration reversed at least once. No depictions of Low made by Menta were exhibited, only Low’s own nude self-portrait where she plays pin-up as femme fatale. This omission endows Low’s presence behind the lens with an unfortunately ethnographic feel, giving the impression that the two artists’ obvious affinities serve here, in part, to paper over an unacknowledged power imbalance.

Bronwyn Hack and Heather Shimmen’s Exquisite Corpse (2019) is a less extroverted but equally compelling collaborative effort. Hack and Shimmen use the layering of imagery that is inherent to printmaking to construct a writhing, gangly, Frankensteinian totem of bony and fleshy body parts. The shared gothic sensibility of the two artists is evident in the way that they stitched their images together to create a work that is intentionally not seamless and therefore beautifully formally resolved. I also enjoyed the dialogue between Prue Flint and Cathy Staughton. In addition to Staughton’s acid-trip versions of Flint’s ultra-restrained paintings, it was great to see the erotic drawings Flint produced in response to Staughton’s influence, which condense all of the tension of her larger works into a handful of spidery pencil lines.

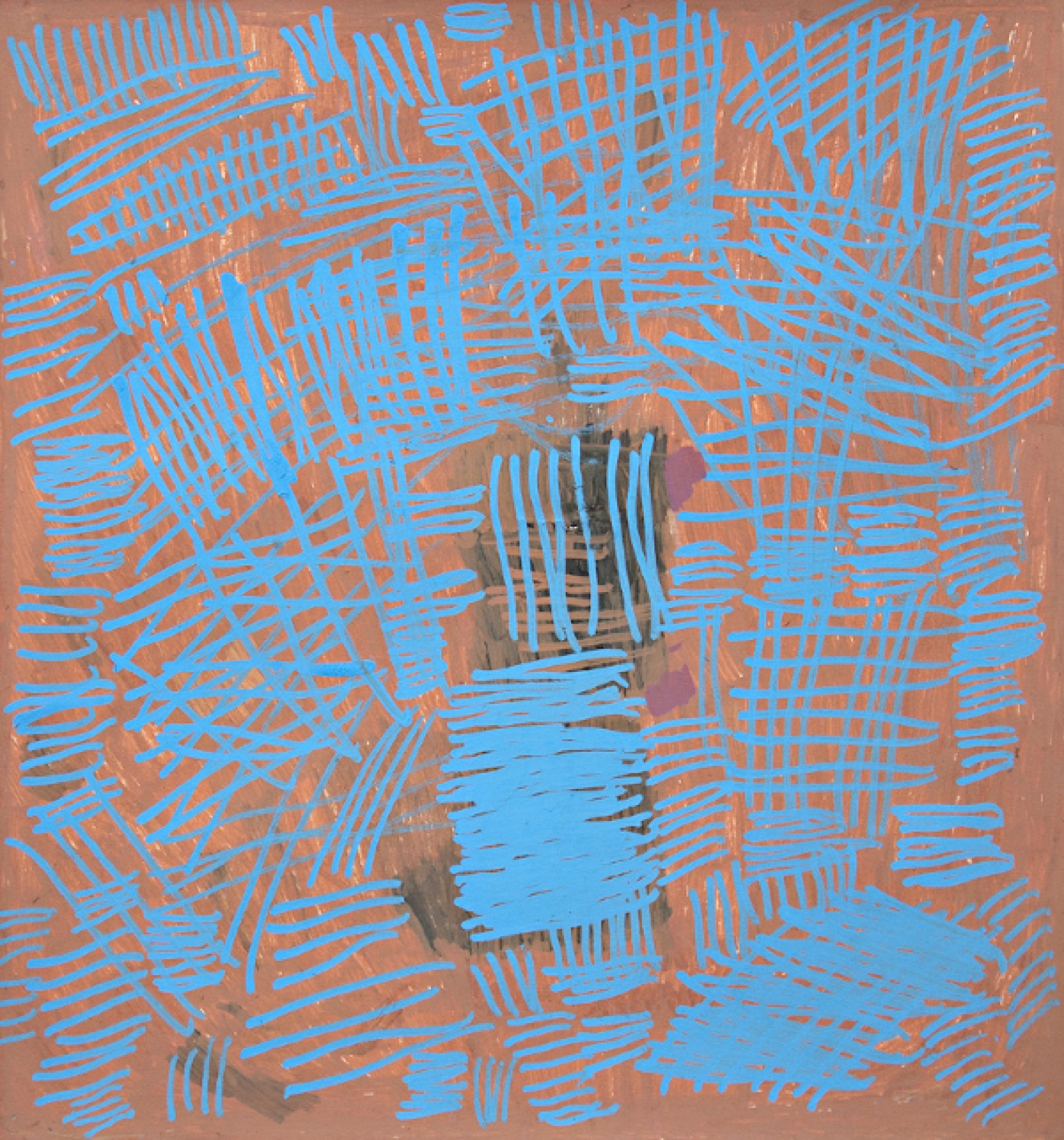

The pairings that work do so because they generate new insight into the art or seem to open new avenues of exploration for the artists. However, some of the exhibition’s affinities are less generative than others. I’m not convinced, for example, that the pairing of Dorothy Berry and Jill Orr reveals any startling new insight into either of their practices, other than their mutual interest in birds. Similarly, while the abstract circle motif common to both Fulli Andrinopoulos and Jane Trengove’s works does take on the rhythmic quality of the lunar menstrual cycle in the context of this feminist show, I’m not sure that this or the obvious formal resemblance between these artists’ works is sufficiently curatorially interesting to justify including quite so many variations on the theme.

In the absence of a compelling affinity between some of the artists’ practices, their relationship seems largely restricted to either formal resemblance or a thesis about the inherent (because gendered) connection of these artists to each other, supported by their bodily relation to the natural world. The shared concerns and common experiences of women, and a spirit of camaraderie, have regained new relevance—and considerable political clout—in our current #Metoo climate. However, gendered generalisations about what Bell calls ‘embodied experience’ can risk falling back into a deterministic and deeply conservative essentialism. This way of thinking not only fails to reflect the complexity of gender identification—a complexity explored with panache in Menta and Low’s performance-photographs. It also risks reducing artistic expression to an instinctive or intuitive impulse and treating artistic affinity as an ‘uncanny correspondence’ welling up from some mythic core of essential subjectivity rather than a strategic alliance constructed by savvy practitioners. This kind of mysticism is—frankly—too close for my comfort to both the 1970s search for an essentially female aesthetic sensibility and unhelpful clichés about so-called ‘outsider’ art.

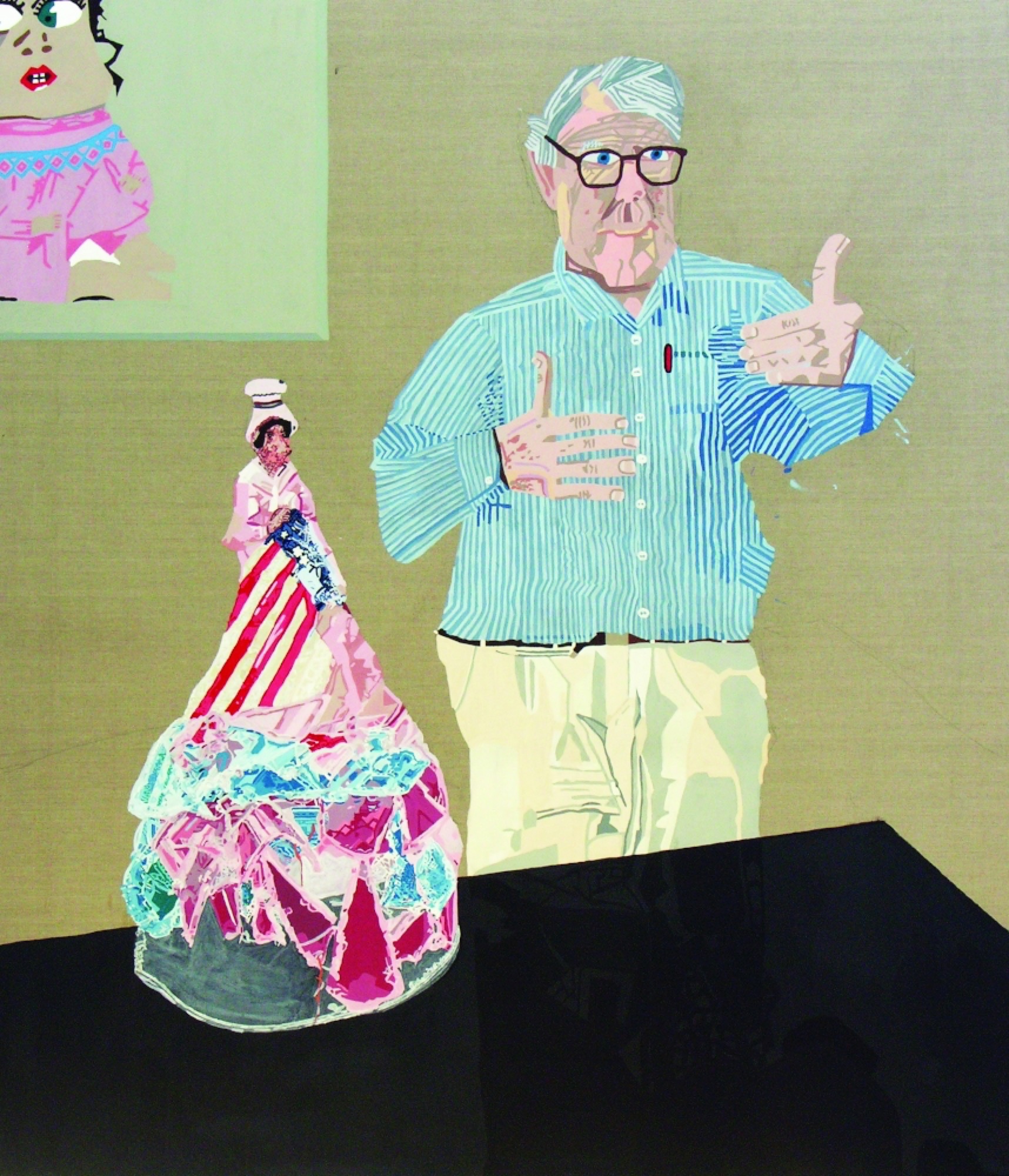

Despite this complaint, the exhibition ultimately succeeds in exploding the binary pairings of its initial curatorial premise into a productive network of affinities between multiple different artists. Initially, I found Bell’s pairing of Lisa Reid’s wonderful portrait of collector Peter Fay with Yvette Coppersmith’s sensual portraits of men superficial. However, the exhibition hang reveals interesting affinities between Reid’s work and the abstract paintings of Helga Groves, Wendy Dawson and Fulli Andrinopoulos that also feed back into the relationship between Reid and Coppersmith’s works. Beyond the banal fact that Reid and Coppersmith have both represented men wearing blue shirts, they also both have an interest in pattern and surface that complicates the relation of figure and ground and sets up a dynamic play between figuration and abstraction.

Affinities are as much in the eye of the beholder (or the curator) as they are inherent to the practices (or female bodies, or life experiences) of artists. It is both creatively generative and politically expedient to recognise and identify affinities, particularly when it helps to synthesise a collective identity out of overlapping experiences of disenfranchisement. However, as the dynamically emerging associations within the exhibition space demonstrate, collectives of identities and art practices can be configured in many different ways.

Anna is a writer and art historian. She received her PhD from Melbourne University in 2018, where she currently works as a researcher and sessional academic.