Tom Roberts, A quiet day on Darebin Creek, 1885, oil on wood panel, 26.4 x 34.8 cm, National Gallery of Australia

Early Impressions: Painters of the Heidelberg School from the National Collection; The Heidelberg of the Heidelberg Artists 1880–1900

Jarrod Zlatic

Art Gallery 275 at the Ivanhoe Library and Culture Hub is about the closest that any of the Heidelberg School paintings could be exhibited relative to where they were originally painted (ignoring private residencies, though some of those nearby houses certainly seem grand enough that they might be hiding one or two). Their current exhibition, Early Impressions: Painters of the Heidelberg School from the National Collection, then, is about the nearest that any of these paintings could have to a homecoming.

There are some potential difficulties in the way of a homecoming; some might contest the nature of this even being their “home,” given these paintings’ inextricable and intimate connection with the fiercely contested notions of nationhood. Talking to someone else who had seen the show, she commented that, having just read the recent Yoorrook report, she couldn’t help but see the paintings as “just spooky.” The painters themselves might also have denied it as home, seeing it as just one of many camps, whether Heidelberg, Box Hill, Mentone, or Sirius Cove. But it was not only that this period at Heidelberg produced several now-iconic paintings, but that it was the most permanent and public manifestation of these various camps. The popularity of the Heidelberg camp allegedly became something of an embarrassment to the core painters, with parties of eighty to a hundred people ascending to their house on the hill.

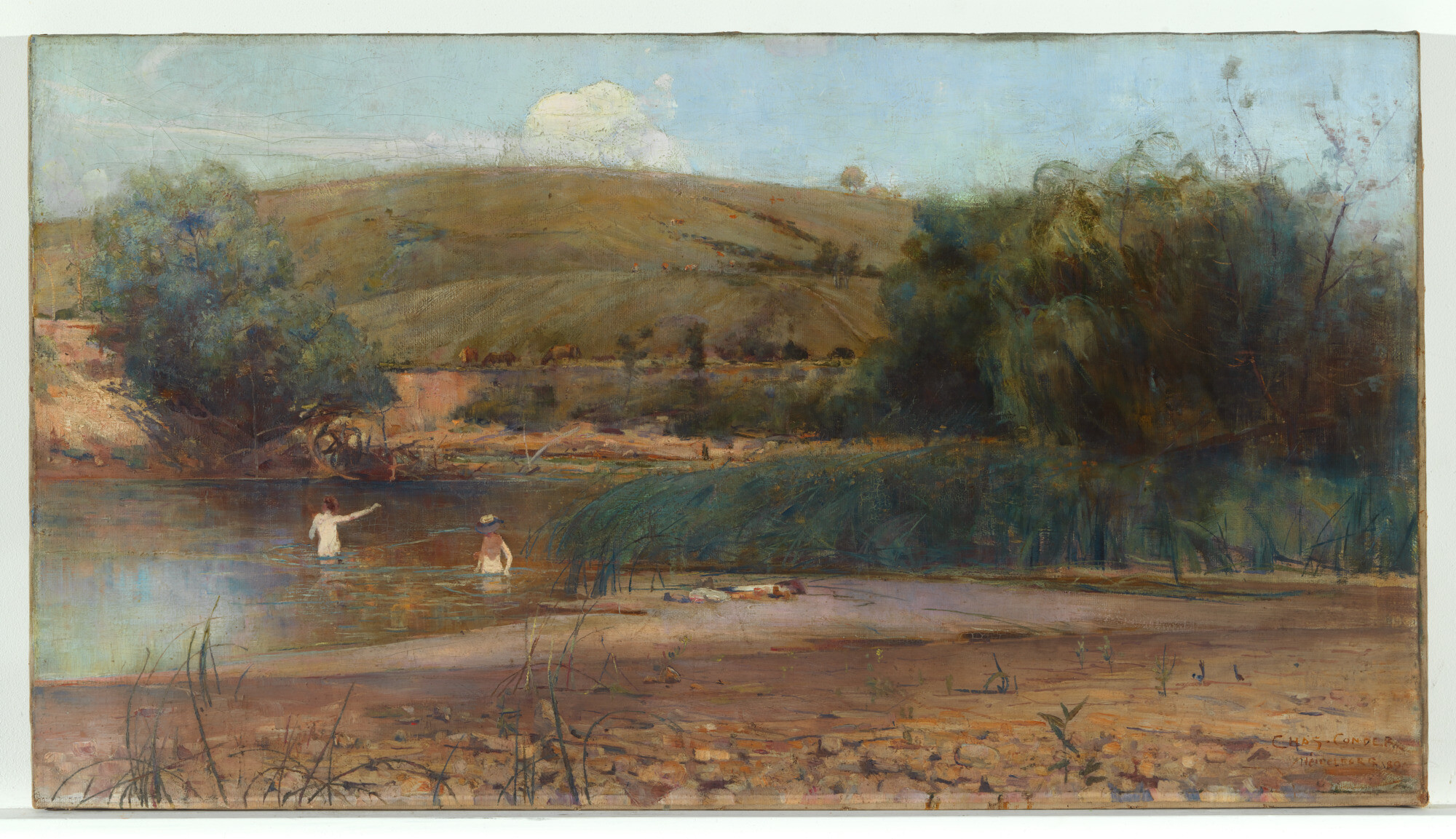

Charles Conder, The Yarra, Heidelberg, 1890, oil on canvas, 50.6 x 91cm, National Gallery of Australia. Gift of James Fairfax AO 1992.

The works are on loan from the National Gallery of Australia as part of their Sharing the National Collection initiative (the current exhibition is on until 16 January 2026, but confusingly the works will remain on loan to the gallery through mid-2027). The initiative is to share the national collection throughout the smaller regional and council galleries, including a Barnett Newman in Nowra, Andy Warhol in Wanneroo, and Claude Monet and Giorgio Morandi at the Margaret Olley Art Centre in Tweed.

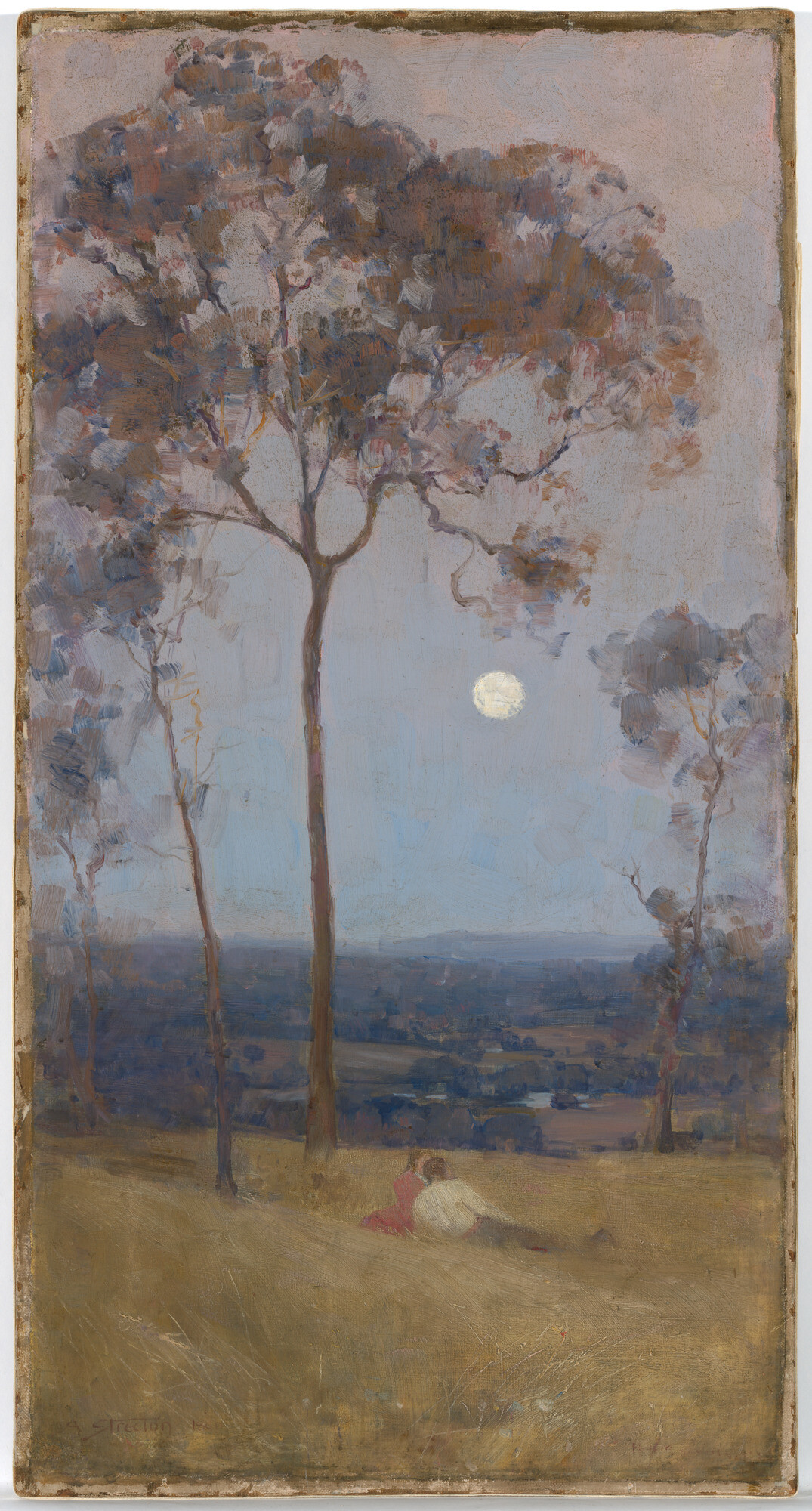

The exhibition curator Steph Neoh has worked within an understandably straightforward constraint in only selecting works that were also painted around Heidelberg (the local landscape approach is an unsurprisingly common approach among the participating galleries). Searching through the NGA collection reveals that this did not leave Neoh with much choice, and the resulting selection is something of a lucky dip. The dual limits of the NGA’s collection and this self-imposed frame mean that, despite the exhibition’s title, there are sadly no “impressions.” Instead of the freshness and weightlessness of their smallest paintings, we have the trio working upwards, on their way to what Roberts would term “machines,” which is to say the big paintings, essentially academic in orientation, on which the Heidelberg School legacy was built. It was this approach that was celebrated as “Rational Impressionism” in 1890 by the Australian-French impressionist painter John Russell when writing to Roberts on Shearing the Rams. There are still patches of indecipherability in the works here, however: the swirl of trees and reeds; the patch of high-key metallic blue in Conder’s The Yarra, Heidelberg (1890) reflecting in the river; the dissolving heat haze of small fires mingling with dry grass in Streeton’s The Selector’s Hut (Whelan on the Log) (1890).

Tom Roberts, A Sunday afternoon picnic at Box Hill, 1887, oil on canvas, 38.6 x 28.7 cm, National Gallery of Australia.

Designation “Early Impressions” might apply best to the two Roberts paintings here, which are from soon after Roberts’s return from studying in London and prior to Heidelberg. A Sunday Afternoon Picnic at Box Hill (1887) is from the time of his first painting camp in Box Hill. According to art historian Helen Topliss, it was Box Hill that had first piqued Roberts’s interest in the Australian bush. A teenage Roberts, freshly arrived from England, had encountered the Box Hill of the 1860s just as it was beginning to be deforested. The Box Hill of the mid-1880s, though, was one that had been denuded, now predominantly orchards and empty lots, which meant the vista, hitherto preferred by landscape painting, was useless. Camping in the remaining tufts of bush, the characteristic cropping of the Heidelberg artists seems to be not just a formal technique derived from photography in the embrace of a “whole image” (which is to say not a Frankenstein-like assemblage of an ideal image), but a consequence of this need to crop out the reality of urban development: that this picnic was taking place on a nature strip, not in nature.

The theme that comes out of the paintings here is along similar lines: a valorisation of leisure, not labour. The long thin horizontal panel like advertising posters or billboards with their depictions of afternoon picnics, romantic weekends away, outdoor painting excursions, and skinny dipping. Still, even if it had not been home, the artists themselves would go on to write to each other reminiscing about the time, lamenting their own inability to ever make their own return.

Arthur Streeton, ‘Above us the great grave sky’, 1890, oil on canvas, 73 x 36.8cm, National Gallery of Australia.

The homecoming quality also means that any critique of the show’s textbook framing feels slightly redundant. Alongside paintings by the trio of Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, and Charles Conder, there are two Louis Buvelots and a Clara Southern, which is either dull or claustrophobic (I can’t decide). These last two artists present both a prehistory and future to the core Heidelberg painters (with Buvelot we look back to the European landscape painting tradition and one of the few artists the group acknowledged; and with Southern, who after passing through the Heidelberg camp would go on to form one of the numerous painting camps that subsequently mushroomed through to Eltham and Warrandyte, we look forward). Individually all the works are nice, but despite there being only eight paintings it somehow manages to be simultaneously empty and cramped. The paintings only take up two of the four walls of the gallery, and consequently the uniform hang also feels crowded. The gallery touts itself as “museum” quality, which can be seen in the security rope that runs across the two walls of paintings, furthering the cramped feeling (one has to crane over to look closely at the paintings, but invigilators have been hired to ensure no one actually does this, though much of the audience, advanced in age and often with vision difficulties, have had issues with this containment zone around the paintings). A homecoming parade; are the works cattle penned in, or are they keeping the cattle out?

Frederick McCubbin, The Lime Tree (Yarra River from Kensington Road, South Yarra), 1917, oil on canvas, 97 x 110cm, private collection. Photo courtesy of Leonard Joels.

Homecoming for these works is most fraught on a practical level, in that any actual, permanent homecoming for these works is unlikely. While the iconic deco town hall that is connected to the culture centre may have a Streeton Room, a Conder Room, etc., it can’t actually have any of these works hanging on their walls in perpetuity, because the Heidelberg School has become among the most expensive within Australian art history. The works have a gluttonous appetite for money and have long been out of a small museum’s reach. This ongoing saliency could be seen just last month at the auction of a late Frederick McCubbin work, The Lime Tree (Yarra River from Kensington Road, South Yarra), 1917—nice, but slightly too mannered when compared to other late McCubbin works—selling at auction for \$1.2 million. That is, double the estimate.

Banyule Council’s art collection is hemmed in not only by being priced out, but also by the presence of nearby Heide. The Heide collection comprehensively surveys the other end of Heidelberg’s significant contribution to Australian art history. That so much art history, as it relates to the local area, is so well accounted for elsewhere means that it must dictate the Banyule collection policy, requiring all acquisitions to “contribute to the ‘most recent ideas and theories’ in contemporary art practice” as per the Banyule Art Collection Policy 2017–2022. This would presume experimental and forward-thinking additions but seems to result in exceedingly average works being acquired (though in this we might say they are no different from much of the work acquired or commissioned by the NGV). However, it is hard to actually make any assessment of the gallery’s overall collection as it is completely undigitised, a straggler compared to many other council collections. A recent filler exhibition of their permanent collection provided some indication with a lot of the standard Schwartz stable that clogs every Australian permanent collection, in this case works by John Nixon and Mike Parr, I think. I think, as trying to look back over past shows is difficult as they do not keep a list of previous exhibitions. Instead, the gallery remains an ahistorical minor segment of the main council website providing ratepayers with continual updates.

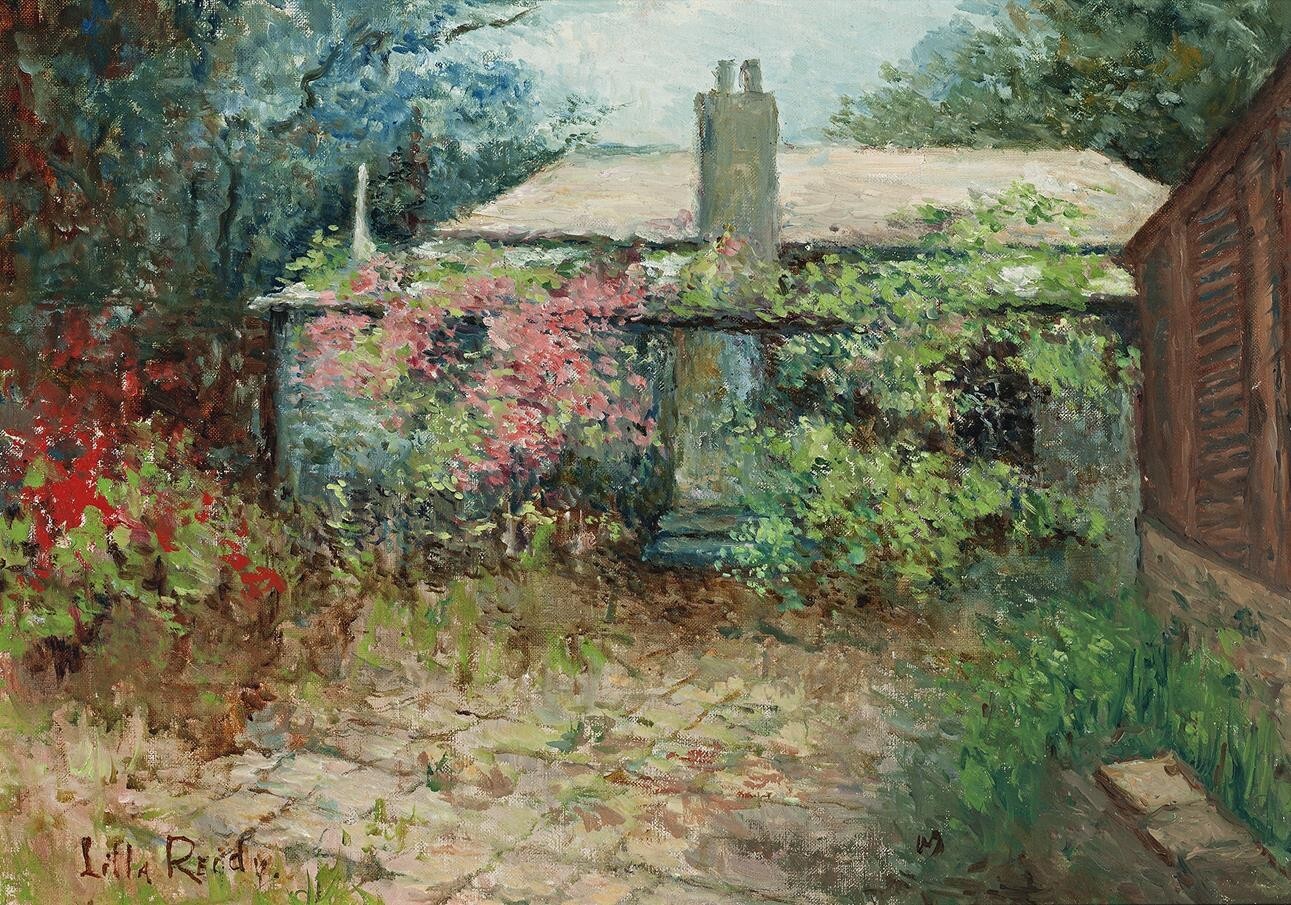

Lilla Reidy, Old Home - St Ninian’s, Brighton, c.1895, oil on canvas, 35.5 x 51 cm, private collection. Photo courtesy of Deutscher and Hackett.

A similar problem also faces the exhibition’s half-sibling show, which is on concurrently at the Heidelberg Historical Society on the other side of Mount Eagle, The Heidelberg of the Heidelberg Artists 1880–1900. The Heidelberg Historical Society is unapologetic in highlighting their collection’s limits. The introductory panel to the exhibition upfront acknowledges the lack of original paintings and asks that “if any visitors would like to DONATE an ORIGINAL work to the society, please ask volunteers for a form!” (sic). In lieu of originals we have mostly card-mounted photo prints, presumably as the light-filled room and the society’s collection of delicate old photography don’t mix. AI fills in some gaps; one of the larger images displayed is a re-colourised photo of a horse-drawn cart sauntering down a tree-lined dirt road surrounded by paddocks and hills, but the arms of the trees thin out in that telltale style of current AI rendering, with its estimation of limb tips spiky and artificial, a literal vision of an uncanny valley.

I wasn’t sure what to expect before visiting but was hoping for an exploration of late nineteenth-century Heidelberg’s landscape through the society’s photographic and archival collection, but the emphasis is on the artists’ extensive networks of patronage and friendship in the local community. There are some collection items: an impressive panoramic view, the Kerr Brothers’ Photographic Studio’s Panorama of the Yarra Valley from Mt Eagle (c. 1916), a single, impossible vision made from three panels, the sort of composite from which the Heidelberg artists were escaping. The highlight, however, is a charming little painting lent to the society, a rather wonky piece by the second-wave Charterisville School impressionist Lilla Reidy. Reidy was a student of Emanuel Phillips Fox, later taking over the running of his Melbourne Art School in Eaglemont, later still establishing a women’s art colony, Petite Bohème, at Black Rock. Her Old Home St Ninian’s, Brighton (c. 1895) is likely from this later time. Reidy has everything wobbly and spattered. Its lurid colours and dissolving forms look strangely far forward, anticipating the complete absorption of Impressionist principles in acrylic amateur paintings of the 1960s and 1970s.

Corner of Lower Heidelberg Road and Burton Cres. (left hand side courtesy of Google Earth, right hand side by author)

The Reidy painting also puts into relief how lean this showing of NGA works is; there are none of the varied individual stylists of the “School” (McCubbin, Walter Withers), or the French style of Fox and his Charterisville-school pupils. The long trend of exhibitions on Australian Impressionism now is also expansive, concerned with Impressionism and Australia in general. Moving beyond Heidelberg to its sinuous Art Nouveau variations in Sydney, as well as all those artists working in France and abroad. The distinct Anglo-Australian strain of Impressionism, which began with Roberts’s adoption of Whistler’s neutral brushwork, is now one of many variations. But this leanness offers a return to first principles, one inadvertently mirrored in a recent urban renewal undertaking in East Ivanhoe. A renovation of a street corner on the main shopping strip saw the quiet removal of an information panel on the history of painting in Heidelberg. This one that had been removed was focused on Fox’s associate Tudor St. Tucker George’s Young Girl in a Garden c. 1896. George was another artist who also helped to run the Melbourne School of Art. There are several of these types of panels scattered around the area, part of the local history initiative/tourist trail “In the Artist’s Steps,” though I’ve only ever come across one other, a rather dilapidated one down in the Banyule Flats. A government-funded initiative overseen by art historian Andrew Mackenzie that outlines a generous history of the Heidelberg School, it is remarkable their web-hosting and domain fees are still being paid (although the website hasn’t been altered in at least twenty-two years, one can still download a series of lectures formatted for RealPlayer). On the other hand, I recently took a tour of a nearby primary school and was curious to see if the art room would have a Streeton or Roberts poster on the wall in the same way a picture of the Queen once would have been stoically displayed (there wasn’t).

Mary Meyer, Streeton - Still Flows the Stream (small copy), c1890s-1930s, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Australia. Bequest of Mary Meyer in memory of her husband Dr Felix Meyer 1975.

A return to first principles provides one way to approach the current limits of the broad conception of Impressionism and Australia. Beyond the famous innovators there remains a disinterest in the endogenous strain of the Heidelberg School style which developed afterwards. This was a mixture of home schooling and the archly academic that went on past Federation and through to the interwar period and beyond. These are now mostly forgotten painters, although some were part of the various artists camps: Tom Humphrey, J. Llewellyn Jones, Leon Pole, and Mary Meyer. Later came the academic impressionists, including William McInnes, the much-underappreciated W. D. Knox, or the once overappreciated Ernest Buckmaster (Australia’s highest-selling artist for a time).

Understandably, this style has been downgraded for several generations now due to its former ubiquity and gauche aesthetic conservatism, not to mention commercialism and association with cultural chauvinism (supposed and actual). But mostly criticism of the Australian landscape school might cite its supposed monotony in the repetition of style and subject—that basically the work is boring. This strangely repeats those criticisms that were originally levelled at the Australian landscape, such as Barron Field’s 1822 complaint about the eucalypts and their evergreen monotony. The paintings in this current exhibition provide once again an answer to Field’s evergreen question “What can a painter do with one cold olive-green?”

Jarrod Zlatic is a critic and musician from Melbourne, Australia