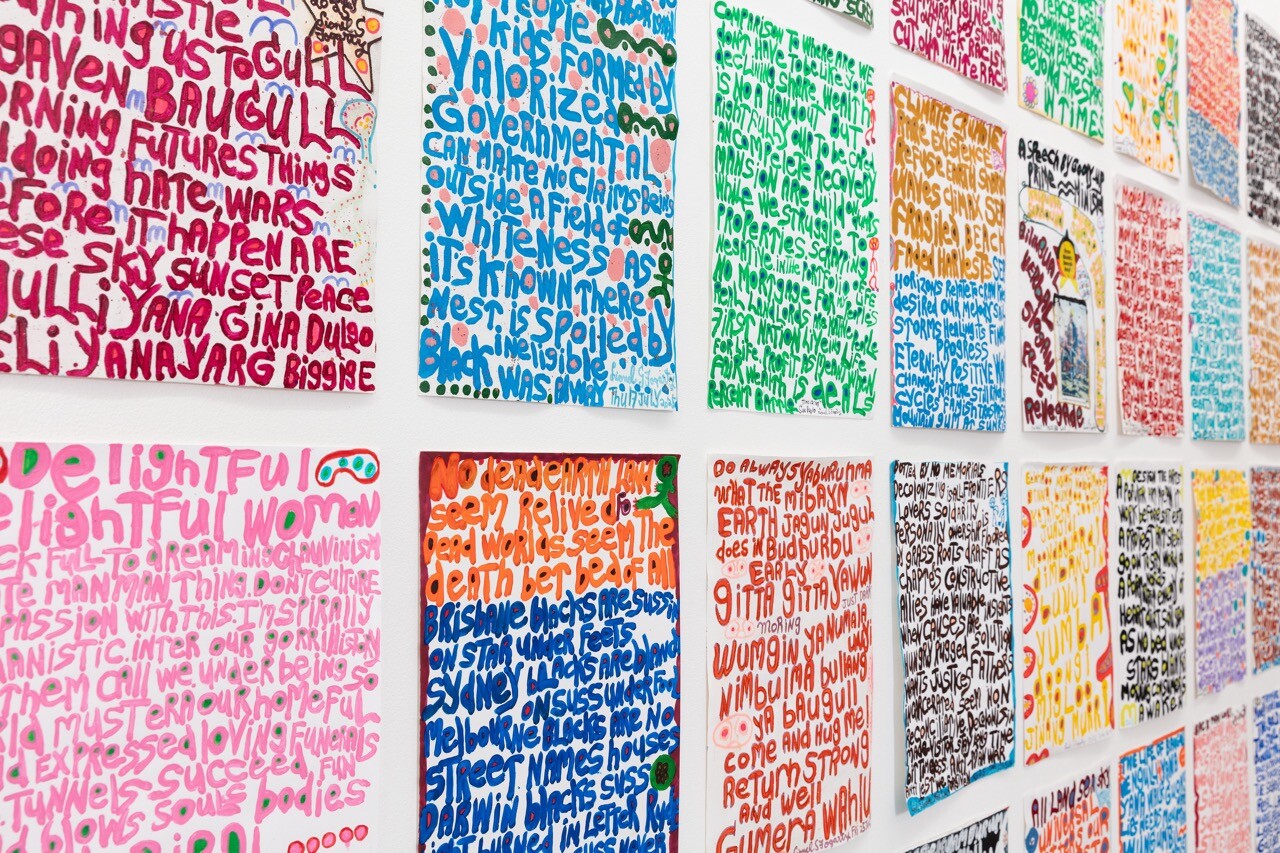

Giselle Stanborough, … Take My Hand, Give Me a Sign (2025). Photo by Josef Ruckli, courtesy of Institute of Modern Art.

Desire is a Machine

Vincent Lê

If schizophrenia is the universal, the great artist is indeed the one who scales the schizophrenic wall and reaches the land of the unknown, where he no longer belongs to any time, any milieu, any school.

—Deleuze and Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia

Curated by Stephanie Berlangieri, Desire is a Machine (2025) sees the Institute of Modern Art assemble an appropriately anarchic multiplicity of both Australian and international artists, including those with schizophrenia and other mental health conditions. They use installation, print, drawing, and video to explore more or less consciously—or better yet unconsciously—the influential collective work of French philosophers and “schizoanalysts” Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.

In their seminal book Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972), French theory’s favorite odd couple swing their pens like swords against the psychoanalytic establishment. Taking both the Freudian and Lacanian schools to task for obsessing over the neurotic individual, Deleuze and Guattari challenge the monotonous interpretation of psychological symptoms as invariably stemming from a fundamental lack or failure to work through the Oedipal complex and integrate traditional familial structures as the unconscious’ only acceptable object of desire. They oppose this normalisation to their own practice of “schizoanalysis” that remodels the unconscious on the psychotic or what they also call the “schizo.” The psychotic subject is characterised by their constant scrambling of fixed desires, identities, and social structures so as to remain open to a multiplicity of new desires and creative becomings, which “reach further and further into the realm of deterritorialization.” As the book’s subtitle suggests, and as Deleuze writes in a letter to Guattari, they are especially interested in exploring how “the schizo metonymically expresses the machine of industrial society”; that is, how schizophrenic symptoms are not individual pathologies so much as psychological expressions of larger social conflicts, contradictions, and crises in the world around them. While Anti-Oedipus celebrates modern industrial capitalism as itself schizophrenic to the extent that its relentless technological innovation and ruthless commodification of desires, values, social relations, and traditions profanes all that is sacred in a “generalized decoding of flows,” it also warns that capitalism ultimately comes to subdue and repress revolutionary forces through the very same commodifying process: “what we are really trying to say is that capitalism, through its process of production, produces an awesome schizophrenic accumulation of energy or charge, against which it brings all its vast powers of repression to bear, but which nonetheless continues to act as capitalism’s limit.”

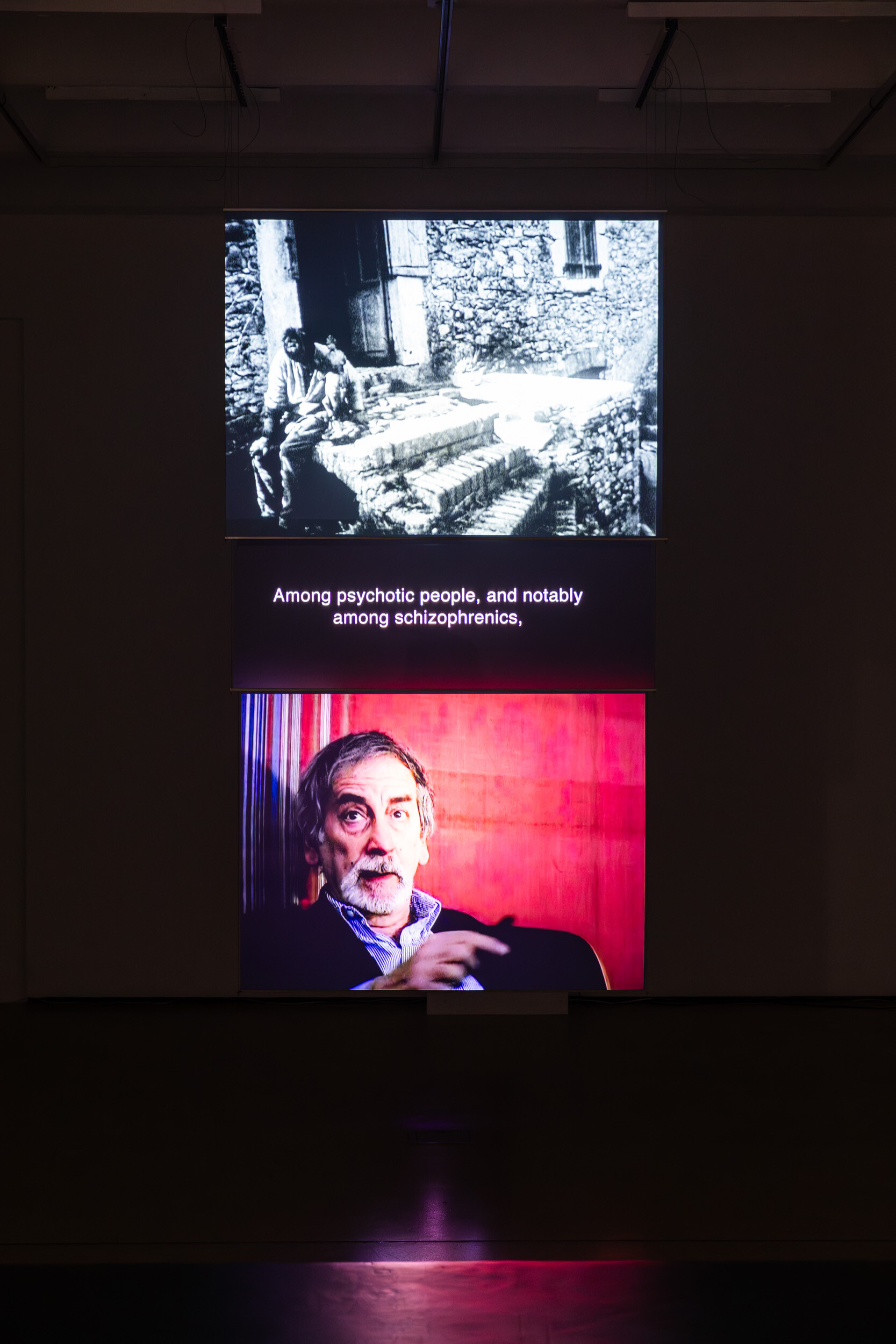

Those visiting Desire is a Machine in search of a more detailed decoding of what Deleuze and Guattari’s schizoanalysis is all about would do well to stroll straight on over to the room screening the video essay Assemblages (2010). Created by artist Angela Melitopoulos and philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato, Assemblages is an hour-long, two-channel installation-documentary exploring the psychological, political, and ecological dimensions of Deleuze and Guattari’s key concept of “desiring-machines” or “machinic assemblages.” It includes fascinating rare footage of Guattari’s efforts to put schizoanalysis into practice at the La Borde experimental psychiatric clinic by having patients and doctors swap roles, switch identities, and scramble social codes—as well as by putting on an annual play in an early radical version of art therapy.

Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato, Assemblages (2010). Photo by Josef Ruckli, courtesy of Institute of Modern Art.

Entering the exhibition with its clinical white walls, nomads and French theory bros alike will immediately feel a connection as they are greeted by a lithographic print of the German physician and science populariser Fritz Kahn’s Man as Industrial Palace (c. 1931)—from the National Gallery of Victoria’s collection—which graces the cover of the 2009 Penguin Modern Classics edition of Anti-Oedipus. In a twentieth-century darker precursor to Pixar’s animated Spinozist masterpiece Inside Out (2015), Kahn’s vision of the human body as an industrial factory depicts our various organs becoming machine parts, with miniature workers operating them in order to produce physiological and cognitive functions like speaking and thinking. This nicely illustrates Deleuze and Guattari’s central gesture—from which the exhibition gets its name—of modelling human desire on machines. Much as machines are assemblages of parts that carry out different functions, so are humans and indeed other organisms composed of “organs” that produce different desires, such as legs for walking, lungs for breathing, smoking, or vaping, and mouths for eating, talking, or spilling the tea. As a science populariser, Kahn pioneered the use of infographics to visualise complex scientific ideas for the general public. Today, his proto-Instagram infographic print cannot help but evoke social media’s algorithmic rewiring of the human psyche and social relations, making really-existing science fiction cyborgs of us all. It thus brings to the fore the way that Deleuze and Guattari not only conceive of individuals but whole societies as machines. Just as individual bodies are organised, “coded,” or “territorialized” like machines in the pursuit of various functions or desires, so are collective social bodies organized by a division of labor for the production of different goods and services necessary for their smooth functioning.

As our two or indeed “crowd” of schizoanalysts—if they are right to say that “each of us was several”—go on to say, since every society is territorialised around certain codes, this means that other possible codes get left out of its desiring production. Social change thus consists in a “decoding” or “deterritorialization” of the present codes by connecting and coupling up society’s machinic parts and organs in new assemblages to let loose the flows of desire—with the most radical deterritorialisation being what they call a “body without organs” at all. It is this process of deterritorialisation, as best embodied by the schizophrenic subject, from which Desire is a Machine takes its principal spark of inspiration—or perhaps demonic possession. Next to Kahn’s print sits artist Aurélien Froment’s Schizophrenic Bricolage (2025), a sculptural reconstruction of the listening device created by the American writer Louis Wolfson, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia at a young age. Unable to bear the sound of his native English language, Wolfson devised this machine to play foreign language radio recordings to shield him from unwanted exposure. He also developed a personal system for immediately translating any English words he heard into foreign equivalents with the closest sounds, meanings, and associations. Taking up two more walls is Froment’s Index of Coincidences (2025), which is inspired by Wolfson’s instantaneous translation system. In the style of art historian Aby Warburg’s incomplete Mnemosyne Atlas (1927–29) that traces the compulsion to repeat ancient motifs in the modern unconscious, or artist Patrick Pound’s vast collection of photographs and objects for the NGV’s Patrick Pound: The Great Exhibition (2017), Froment’s Index of Coincidences assembles a collection of magazine images and printed matter—housed in The Reader’s Digest Complete Do-It-Yourself Manual (1969) binder—to create a visual map of Wolfson’s memoir Le Schizo et les langues (1970). Diehard fans of the D&G Extended Universe will recall that Deleuze wrote the introduction to Wolfson’s book. All of this is very much in keeping with Deleuze and Guattari’s second collaborative work, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (1975), and its key concept of “minor language”: a subversive way of speaking in the dominant or “major language” to undermine it from within like an undercover agent or Trojan horse, and thus “become a nomad” or “be a stranger, but in one’s own language.”

Aurélien Froment, Index of Coincidences (2025). Photo by Josef Ruckli, courtesy of Institute of Modern Art.

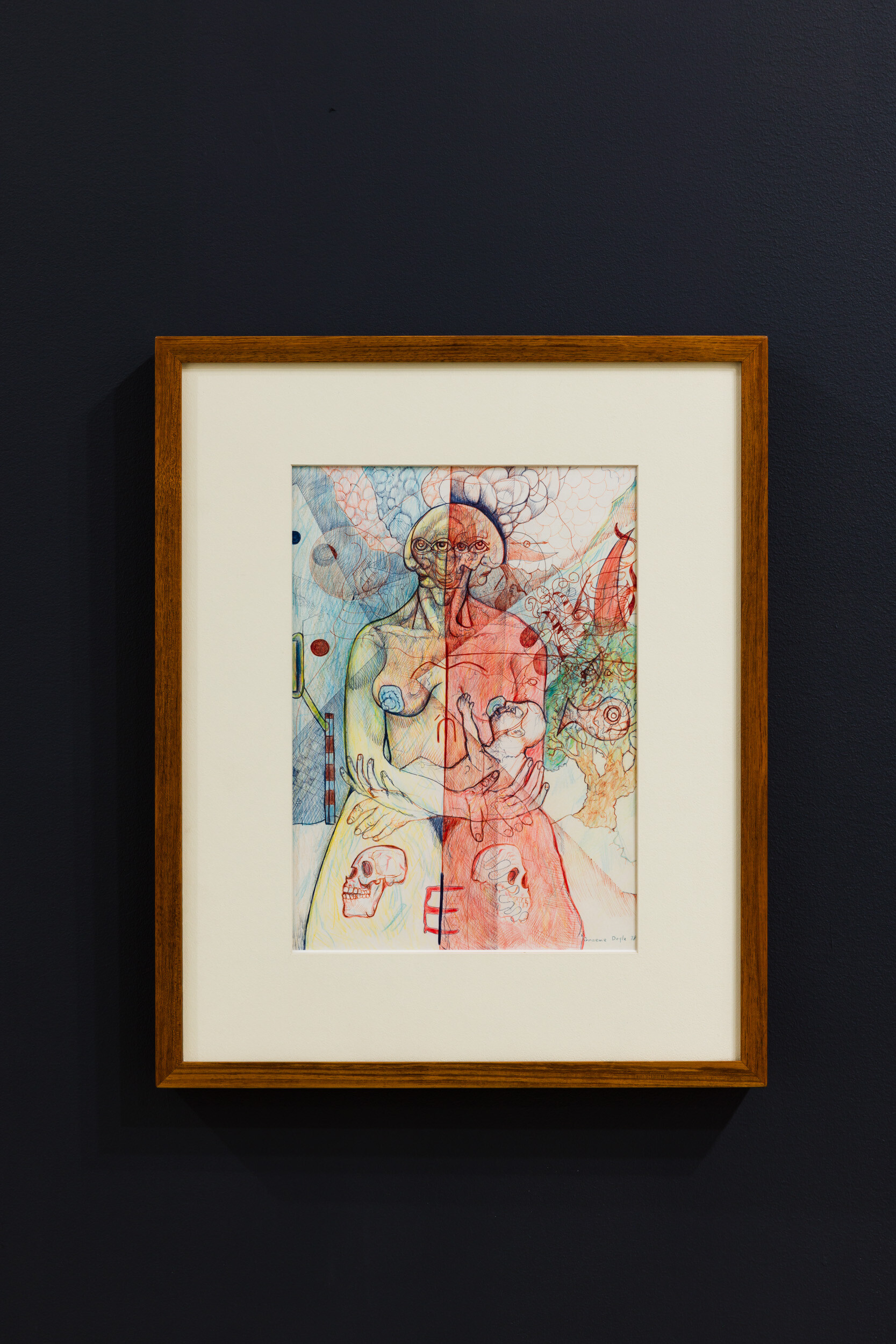

The fourth wall in the exhibition’s entrance room presents the pen and pencil drawings of the late outsider artist, poet, and musician Graeme Doyle, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder at age eighteen. These untitled works from the late 1970s come from the Cunningham Dax Collection in Melbourne/Naarm, which archives art produced through therapeutic programs at Victorian psychiatric hospitals. Accompanied by audio recordings of his poems, Doyle’s drawings depict human forms—particularly female nudes—fragmenting and multiplying into grotesque shapes and alien anatomies. In crossbreeds more monstrous than the human-animal hybrids on the island of Dr. Moreau or the humanzee in secret Soviet labs, there is a particular emphasis here on distorting and mutating the human face, giving it a beak or reptilian snout for a mouth or multiple heads and eyes. Some of the drawings carry religious overtones, such as one resembling baby Jesus and Mary in motion so that she appears to sprout multiple eyes and heads and Escher-like hands, along with skulls on her thighs protruding like bad tattoos. Doyle’s drawings exemplify schizoanalysis’ refusal to conform to a static identity—or what Deleuze and Guattari also call “faciality”—by fracturing the ego’s narcissistic mirror reflection in a process of perpetual becoming that no clinical diagnosis can completely pin down. “Beyond the face,” they say in A Thousand Plateaus (1980), the sequel to Anti-Oedipus, “lies an altogether different inhumanity: no longer that of the primitive head, but of ‘probe-heads’; here, cutting edges of deterritorialization become operative and lines of deterritorialization positive and absolute, forming strange new becomings, new polyvocalities.”

Graeme Doyle, Untitled (c. 1978). Photo by Josef Ruckli, courtesy of Institute of Modern Art.

The exhibition’s deterritorialisation of the face continues as one moves from the hospital ward-like room to a dark curtained theatre. We find here three video works by the Ueinzz Theatre Company, a São Paulo-based troupe of both professional and non-professional actors. As depicted in Archichroma: New Romanticisms for Somber Times (2017) and Artist Talk (2018) made in collaboration with filmmaker Pedro França, the ensemble explicitly conceives of theatre as a schizoanalytic practice where the actors work together to create characters, swap roles, improvise identities, and forge new connections. As one actor puts it, “theatre is a place to take a break from the world and to die a little.” In the third video The Handbook of Facial Expressions 1 and 2 (2018), actor Rodrigo Sano Calazans explores how subjectivity is constructed—as well as deconstructed—particularly through our facial expressions. As the video’s form of a YouTube vlog suggests, this seems truer than ever in our meticulously selfied post-Facebook age.

Ueinzz Theatre Company, The Handbook of Facial Expressions 1 and 2 (2018). Photo by Josef Ruckli, courtesy of Institute of Modern Art.

Leaving the cavernous theatre, we find ourselves as if in a rebellious teenage boy’s messy bedroom before artist Stuart Ringholt’s Yoga Art (2001/25). This installation gathers his diaries, hospital records, x-rays, family photographs, drawings, posters, paintings, clothing, and other memorabilia and personal belongings in an effort to make sense of his experience of psychosis after travelling to India in the early 1990s. In the original performances that these set materials are from, Ringholt returned to significant sites from his past, such as Perth’s Graylands Hospital and Claremont Football Club, using roleplay and costume to embody Jesus Christ, a footballer, and other personas that emerged during his psychotic break. By returning to familiar places only to deterritorialise the déjà vu and bring out the uncanny, Ringholt’s second coming traces a self that has been splintered between recovery and psychosis, transubstantiation and apocalypse, creation and destruction. One of the installation’s scrawlings describes Ringholt sleeping in the same bed with his mother while his father slept in his room. What could be more literally Anti-Oedipal than that?

Stuart Ringholt, Yoga Art (2001/25). Photo by Josef Ruckli, courtesy of Institute of Modern Art.

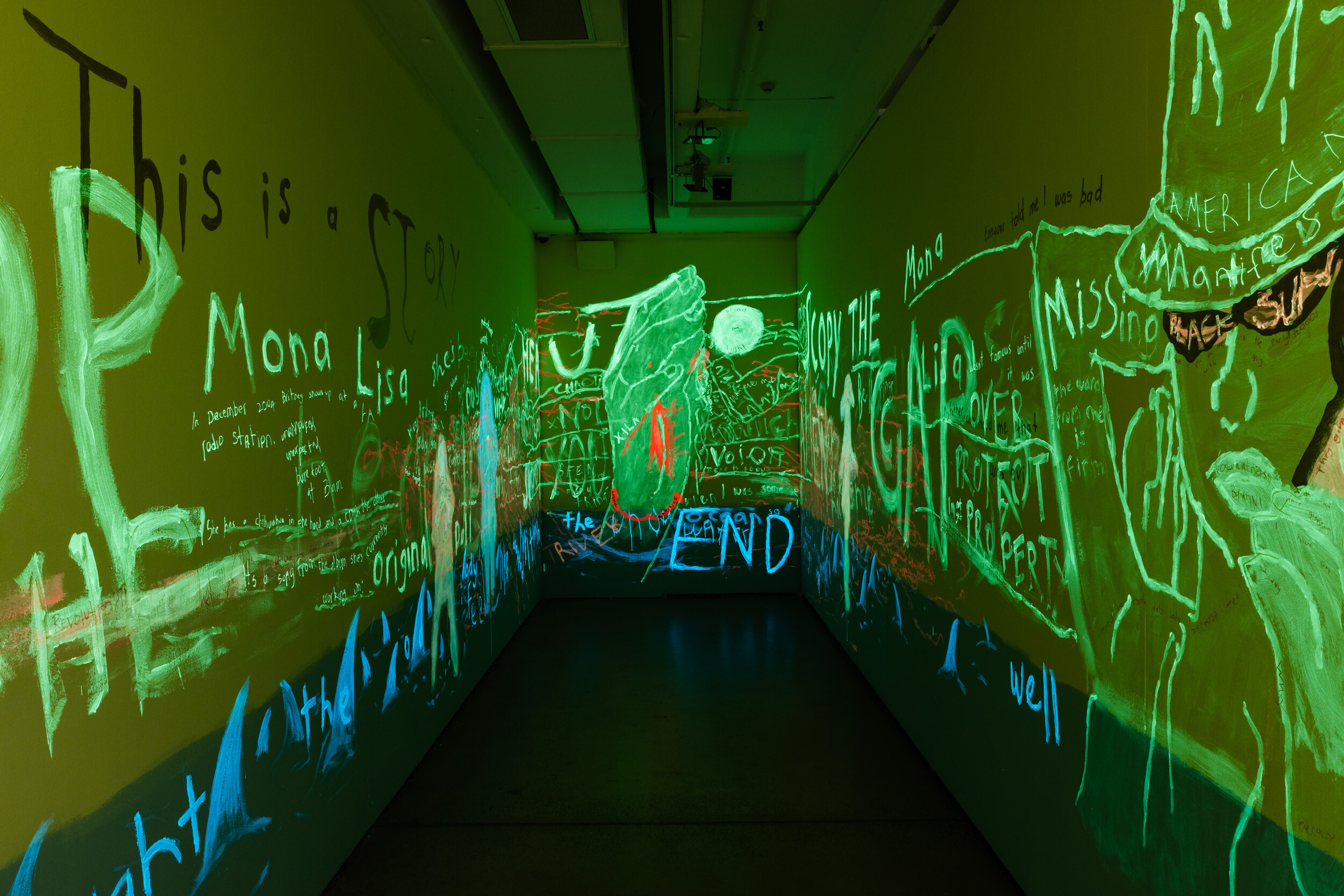

As one enters the last room through a door installed at an odd angle so that it never completely closes, the lights counterintuitively turn off only to reveal artist Giselle Stanborough’s … Take My Hand, Give Me a Sign (2025), a glow-in-the-dark mural made visible under UV light. This fluorescent fresco depicts Britney Spears’ very public life of spectacular music performances, paparazzi incidents, and scandalous meltdowns as symptoms of how the toxic media, music, and entertainment industries not only exasperate mental health struggles, but also actively encourage and exploit them as a source of profit. It is hard to imagine a more contemporary illustration of Deleuze and Guattari’s idea that capitalism’s creative destruction melts all that is solid into air just as much as it hardens everything fluid in turn than the spectacle around Britney—or in more recent times Justin Bieber yelling, “money, money, money, money, money!” at the paparazzi. In the neon colour of advertisements, Stanborough has graffitied slogans like “Industrial Revolution???” and “Protestant Work Ethic” (after Max Weber’s book tying Protestantism to “the spirit of capitalism”) over the Princess of Pop. This lurid swirl of pink and yellow further recalls Deleuze and Guattari’s conviction that pathologies are less symptoms of individual psyches and more those of larger social ills and economic depressions. At the same time, the nods to the pop star’s efforts to break out of her exploitative conservatorship (#FreeBritney!) and bizarre knife dances on her Instagram page perhaps betray her continual capacity to reinvent herself and create new lines of flight. As she sings in her biggest smash hit, “when I’m not with you, I lose my mind / give me a sign / hit me, baby, one more time.”

Giselle Stanborough, … Take My Hand, Give Me a Sign (2025). Photo by Josef Ruckli, courtesy of Institute of Modern Art.

Stanborough’s installation naturally raises the issue of romanticising artists’ mental health conditions. This also comes across in Ringholt’s installation, as close inspection of the anarchic assemblage leads us to clinical hospital records and an emotional letter from his father, which divulge his psychosis’ true toll. While Anti-Oedipus largely encourages us to break out of all straitjackets and “destroy, destroy” without restraint, by the time of its sequel A Thousand Plateaus Deleuze and Guattari themselves come to advise a more cautious “art of dosages”—or more precisely microdosing—if we are to avoid deterritorialising too far into self-harm, sheer madness, death, and social collapse. By exhibiting artists with real psychological struggles, Desire is a Machine appears to implicate not only itself and Deleuze and Guattari but us visitors and art institutions more generally for all too often making a spectacle out of trauma and suffering. For the most part, however, the exhibition is more in the joyous, irreverent spirit of Anti-Oedipus in its suggestion that art does not have to be the kind of therapy so common in today’s care culture, which strives to “rehabilitate” broken subjects back into conformist social reality. Artistic practice can also be about breaking down the sense of self even further to explore those escape routes out of repressive social norms altogether. As one of Ringholt’s scrawlings pithily encapsulates contemporary care culture’s conformist ethos, “health = de-programming desired persons.” More subversively, the same work entertains another possibility: “psychosis = the role playing of desired persons” who we really want to be.

In Min Tanaka à La Borde (1986), one of three films screened to accompany the exhibition, filmmaker and La Borde medical intern François Pain captures the Japanese Butoh dancer Min Tanaka’s performance at the clinic. Through grotesque movements and contorted expressions that break with his formal training in ballet and modern dance, Tanaka channels the schizophrenic scrambling of codes to become a shamanic body without organs (certainly much more so than that other notorious Deleuzian and Australian breakdancer Rachel Gunn/Raygun, who wrote her PhD thesis on Deterritorializing Gender in Sydney’s Breakdancing Scene). As this experimental avant-garde artist starts to look and move a lot like some of the patients around him, Tanaka evokes an admittedly romantic and perhaps even cringe idea—albeit one that I at least believe that Desire is a Machine is right to bear repeating: a true art institution is simply anywhere that the inmates are running the asylum.

Vincent Lê is a philosopher, PhD graduate from Monash University, and teacher at Monash, the New Centre for Research & Practice, and the Melbourne School of Continental Philosophy. More of his ravings can be found in Urbanomic, Un Magazine, and Art and Australia, among other publications. He also writes at vincentl3.substack.com