The giant arched doors swing open to the street—once kept shut before the glazing was added. Photograph by John Gollings.

Central Goldfields Art Gallery

Hannah Zhu

It takes a village to raise this gallery. I’m standing in the Central Goldfields Art Gallery in Maryborough, recently refurbished by Nervegna Reed Architecture. One foot rests on a concrete floor from 1861, the other on a slab poured in 2022. My eyes wander across flaming red doors, historic brick walls, and white plastered skylights. My heart carries voices of the Dja Dja Wurrung people, nineteenth-century settlers and Gold Rush prospectors, and architects and gallery attendants. The gallery asks its people: “How do buildings tell stories of our contested past? What if they were violent? What if they were loving?”

View from Neill Street—cluster of red-brick buildings. Photograph by John Gollings.

Maryborough has The Avalanches, the train station, and now, the newly refurbished art gallery. Located on Dja Dja Wurrung country in central Victoria, it is a two-and-a-half-hour V-Line away from the Melbourne CBD.

It’s difficult to mention Maryborough without its famous train station—big, indeed, with an impressive four-sided clock. The gallery, a ten-minute walk away, also boasts a big bell tower, though it no longer houses the fire bell.

The former fire station presents itself as wholly intact to Neill Street. Red brick dominates the neighbouring heritage buildings—well-preserved fabric where my Chinese Gold Rush ancestors once walked. Two gigantic arched doors, red with sans-serif “CGAG” letters, announce the gallery’s presence, reminding me it’s 2025, not 1855. Above rises the majestic 1888 bell tower, now bell-less but embedded with stone plaques and street signs.

Garingilang Gatjin Wii with the “sun/moon” wall and the bell-less fire tower behind. Photograph by Nervegna Reed.

Behind the tower lies the Indigenous Interpretive Sculptural Garden, designed under the leadership of Dja Dja Wurrung Elders and artists who formed a wartaka, or advisory group, supported by DJANDAK. A loose palisade fence—more dancing logs than barrier—leads to a Yarning Circle surrounded by rockwells, grinding grooves, and colourful native plants. Even though I’m here alone, the air is filled with inanimate spirits. A firepit plaque bears flowing water figures in corten steel, designed by Djaara artist Sharlee Dunolly-Lee. The nearby trench grate matches this finish—humble details creating unexpected joy. True to its name, “Garingilang Gatjin Wii” (Water and Fire Garden), water flows beneath while fire passes over.

Through the red grevilleas and yellow lily billy flowers, the northern facade showcases three distinct materials: red bricks, translucent fibreglass, and corrugated metal in Colorbond “Monument.” These segments correspond to programmatic sequences: gallery, education, and loading. Contrasted with other heritage adaptations that use manic colour-matching, this gradual transformation of fundamental building finishes offers a sensitive touch. The gallery resembles a fire station joined with a farm shed and present-day garage—a fitting context.

The “sun/mooon wall” proves most fascinating. In the fibreglass segment, a brightly lit circle encloses a rectangular glazed window. From the outside, the northern sun hits the fibreglass, creating a milky grey shade with a dim circle and black window—like a pupil patiently watching. From inside the educational workshop, the wall appears as a dark wave of corrugation, the circle shimmering white, transmitting sunlight, the black window now showing the garingilang. I can only imagine its third form as the “moon wall” at night, glowing with soft yellow tones against a dark blue sky. This immaculate manipulation of material and lighting properties pleasantly surprises me: a shared cultural mythology that gently rises above the garingilang, while simultaneously connecting it back to the gallery. Now I want a “sun/moon wall” too.

The “sun/moon” wall seen from the gallery’s workshop space. Photograph by John Gollings.

Now we enter the gallery.

“The old timber door entry was replaced with glass,” gallery attendants Andy and Sandy inform me. “You used to not be able to tell whether the gallery was open—the large arched doors were concealed.”

“You used to walk in and just see a service unit on the wall, then to your left was the reception desk”, they gesture with all four hands, “and to your right you had to loop around a tiny corridor to get to the back,” and now with all four feet. “It was not great,” added Sue, the third attendant.

The architect came in and optimised the space. To follow, I’ll discuss the three main operations by the architects that have proven to be less than straightforward to assess: an attitude of play with heritage, enabling ways to see differently, and subverting imperial methods of “erasure” to foster plurality in storytelling.

Careful infill of the brick wall—just enough added for the building to function, neither revealing nor concealing more than necessary.

The gallery’s concrete floor is thought to be the original 1861 mix (right), with a later extension in a different mix. Photographs by the author.

First, we play. Play is respect and denial simultaneously. Nervegna Reed oscillates between both, teasing the historic fabric. Most original brickwork remains at the entry, the two oldest walls flanking the reception. The bricks reveal a time-lapse—varied colours, textures, conditions. Where historic walls meet the new automated glass entry door, minimal mortar fills gaps. Jagged historic bricks rest against thin binding patches, creating fragile beauty with seeming structural impossibility.

Nervegna Reed had fun with concrete floors. Different colours and aggregate densities appear gradually across spaces. The main gallery sits on the original 1861 slab, polished like a foggy lake. The concrete splits at one point—a clear line delineating darker, denser aggregate from a suspected later addition. Most striking are visible footsteps marking a route aligned with timber trusses above—like following nineteenth-century ghosts installing those massive beams. Former residential units retain silhouettes of removed walls, where today’s staff work among yesterday’s spirits.

Multiple storytelling layers emerge through this exhaustive balancing of repair and intervention. These acts commemorate anonymous workers who laid the building’s foundation and spent nights at the brick fire station—everyday people without stone plaques bearing their names—subverting storytelling from a single protagonist’s perspective.

“The view”: looking up to the fire tower, and through the archway in the walls, aligned with the arch at the base of the tower. Photograph by John Gollings.

Following play, we attempt to see. A tower perspective defines the gallery’s most recognisable instance of seeing. Standing at the entry, we look up: white-plastered geometries transform into a skylight offering a low-angle view of the tower’s head. As Toby Reed delicately explained to the AIA Victorian Awards jury, this intends to challenge “the Victorian system of architecture” and “the Victorian ideology.” It’s an unflattering angle—the underside of the historic bell tower, bare with no bell; it’s like a camera placed too low on a video call, revealing your double chin.

This magnificent yet cruel perspective gives people the opportunity to see differently. The entire building serves as a framing device, enabled by the white skylight that temporarily mutes the context. The view is surprising, mildly disturbing, but also loving—a “desire sight” of sorts—a route connecting people in the fire station with the fire bell that rang through the whole town.

So, is this operation loving or cruel? To Nervegna Reed, it’s both. The encounter breathtakingly confronts, evoking guilt and delight, meant to trouble rather than please. The architects respect the tower while denying its established viewport, irritating its grandeur. It asks the first question in a series: how do we truly see when our ways of seeing are inherently entangled with colonial perspectives?

Nervegna Reed’s operation suggests sitting with the discomfort of both tenderness and cruelty, to look, then ask for forgiveness, and to desire outside of our own systematic biases.

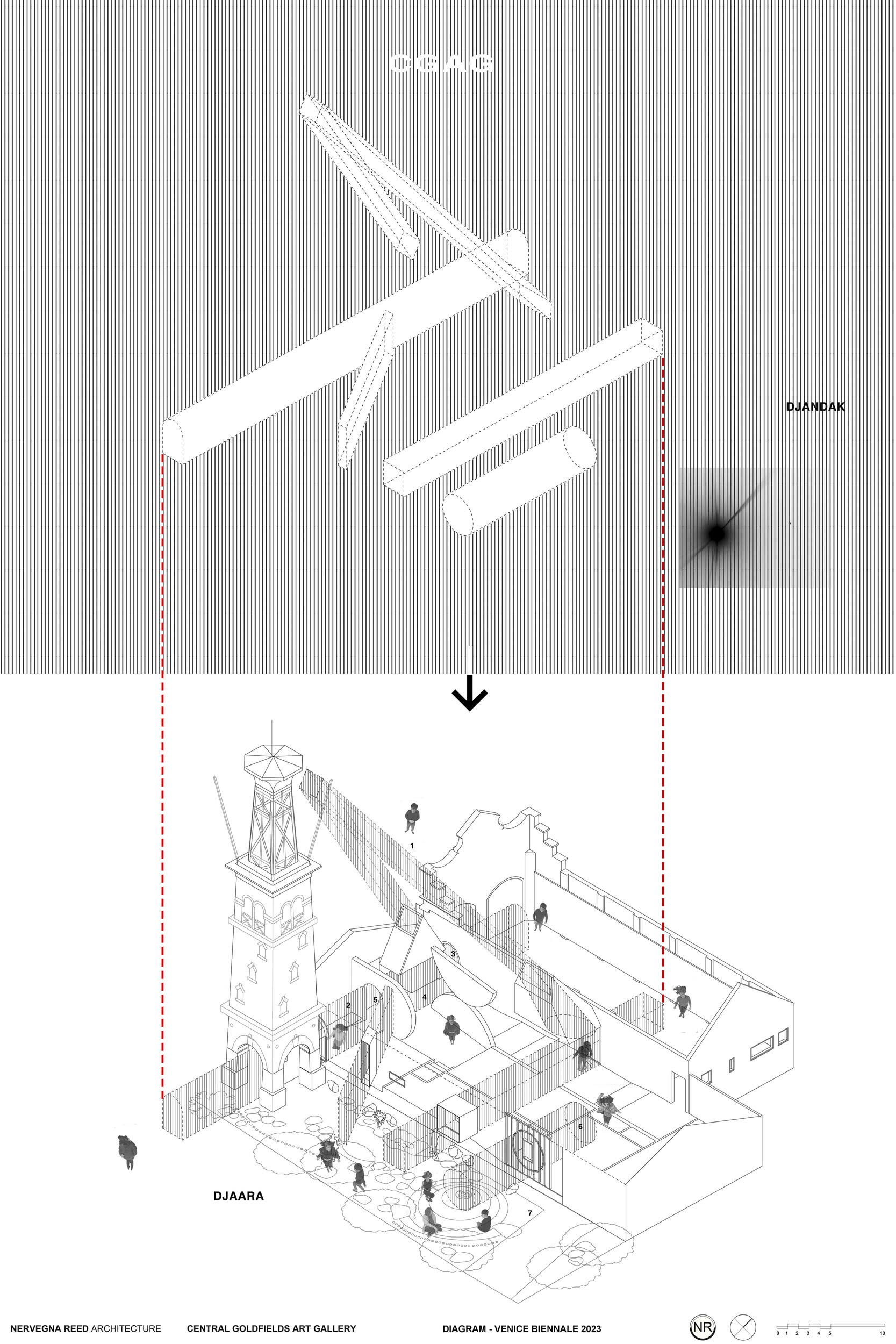

Axonometric diagram tracing sightlines that pass through the historic structure, taking on lives of their own as “space objects” and “displaced geometries.” Image by Nervegna Reed.

“As if we were like Rauschenberg, who rubbed out the de Kooning drawing,” Toby Reed references Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953). “What can you do if you just get an eraser and design through negation?”

The key is “design through negation” and not “negation” alone. Aligning with Rauschenberg, Nervegna Reed demonstrates creation through removal, but instead of erasing the drawing, they are trying to find the Willem de Kooning inside the page. Like a perverse tribute, the operation both submits to and violates figures of authority. Such architectural operations find their inspiration in the methods of Gordon Matta-Clark and later architects like ARM Architecture.

The white geometries of the skylight are far from mute backdrops like gallery walls. The operation is discrete and intense. An axonometric diagram by Nervegna Reed demonstrates this well: grey extruded volumes—”space objects” and “displaced geometries,”—appear to violently penetrate the heritage structure. These operations continue the late twentieth-century postmodernist stance, where semiotics drive spatial design. Kerstin Thompson’s Melbourne Holocaust Museum employs a reversed operation—infill on the heritage facade, much like Peter Zumthor’s Kolumba Museum. Both contrast with NMBW Architecture Studio’s recessive approach at the University of Melbourne Student Precinct, where intervention manifests only through meticulous detailing—perhaps a truer embodiment of Rauschenberg’s method.

The new entry and reception area of the gallery. Photograph by John Gollings.

The need to balance the “white cube” trope and the textural qualities of a historic building comes to mind. Nervegna Reed’s strategy is to vary the intensity of these “displaced geometries” across rooms. The main gallery prioritises function over heritage or ego. At entry reception, architects took the greatest formal liberty—cubes, circles, triangles colliding at varying heights, truly “displaced,” despite uniform whiteness.

On whether the architecture competes with art, Nervegna Reed walks a fine line. The architects engage with clear hierarchy and flexibility, including visible art storage—an increasingly popular strategy in museum architecture nowadays. Sandy demonstrates pulling storage racks in and out, pointing out another dedicated window onto the racks. “It’s so you can see one of the pictures in storage,” she explains. “We sometimes change it up!”

This painting was selected by staff for display in the storeroom portal during the visit. Photograph by the author.

Heritage buildings are both painful and delightful. Every element uncovers events—celebrations and traumas alike. You piece together what happened, imagining previous storytellers’ decisions. Some actions disgust; others enchant. Building means constantly negotiating with the past.

Maryborough had a violent past. Like many Central Goldfield towns, the Gold Rush transformed the land to “upside-down Country”, with anti-social issues still an underlying subplot to the place’s character today. The gallery will continue to catalyse social and cultural change, and historic buildings will continue to house their activities. Like the gallery and garingilang, current practices predominantly involve non-Indigenous architects working with Indigenous co-operations on independent projects— the aim should be for their indistinguishability.

The “erasure” method deployed by the architects is therefore sensitive. Colonial expansion’s direct consequence is holding the eraser to make others disappear—evident in early settlers’ maps where one dominant storyline disrupts place-understanding, and in the near-perfect overlap between nineteenth-century goldfields and Dja Dja Wurrung country boundaries. For non-Indigenous architects to erase colonial history isn’t mere spectacle—Nervegna Reed operates with the constant irritation of an admiration of and spite for our history. When I walk around Central Goldfields Art Gallery, I don’t sense architects content with usual business; I sense ones asking hard questions and taking a stab at answers.

There is nuance also in how erasure can be applied to our colonial history. During the AIA Country Culture Community event last year on Palawa Country in Hobart, Palawa and ngāti wai architect Marni Reti from Kaunitz Yeung Architecture presented the BAAKA Cultural Centre. She explained the reasons for maintaining the prominent corner with the former Knox and Downs store, despite non-Indigenous architects’ initial inclination to remove all traces of colonial history: the Indigenous community cherished the structure as part of their collective memory, and they advocated strongly for its retention. While a different context, and never a one-case-fits-all, this example prompts interesting questions.

A multi-layered approach requires continued case-by-case examination. Non-Indigenous architects contending with their conflicting motivations to culturally self-protect and self-destruct will continue to play assisting, but nevertheless critical, roles in our decolonising future.

Looking back at the entry at the bottom of the ramp: the staff office and art store are to the left, the main gallery space to the right, and a second skylight directs light toward the tower. Photograph by John Gollings.

Nervegna Reed’s “erasure” and “negation” techniques create an inverted palimpsest of Rauschenberg’s method. The architect’s urge to create geometries for both gallery program and artistic agency cannot be elegantly summarised as “erasing de Kooning’s drawing”—rather, it’s a painstaking exercise of subtraction and addition, pushing between white cube and red brick, oscillating between being something contemplative and art-enabling, and grotesque historical manipulation.

The refurbishment acknowledges contested histories in a decolonising context, first posing alternative ways of seeing, then strategically reappropriating colonial “erasure” as a methodology. Minor but significant material reworkings create lasting visitor impact through delicate, case-by-case interventions. This nuanced blend of respect and violation is provocative to other non-Indigenous architects, as we work out ways to decolonise through our work.

Where history collides around the gallery, you confront both enchantment and guilt. Nervegna Reed encourages sitting with discomfort while witnessing colonial heritage violently punctured, painstakingly concealed, or gently repaired. Within these messy operations lies nuanced judgments about whose stories deserve telling. One belongs to Dja Dja Wurrung peoples, told through Garingilang Gatjin Wii—or rather, through curated architectural access from the gallery. Others belong to nameless historic ghosts and spirits of the inanimate materials, such as the “sun/moon wall”. When we tell stories of our past, we have to constantly ask: how will we tell them differently?

Hannah Zhu is an architect, artist, and academic in Naarm/Melbourne. Her work focuses on nomadic ecology and cinematic techniques in the built environment.