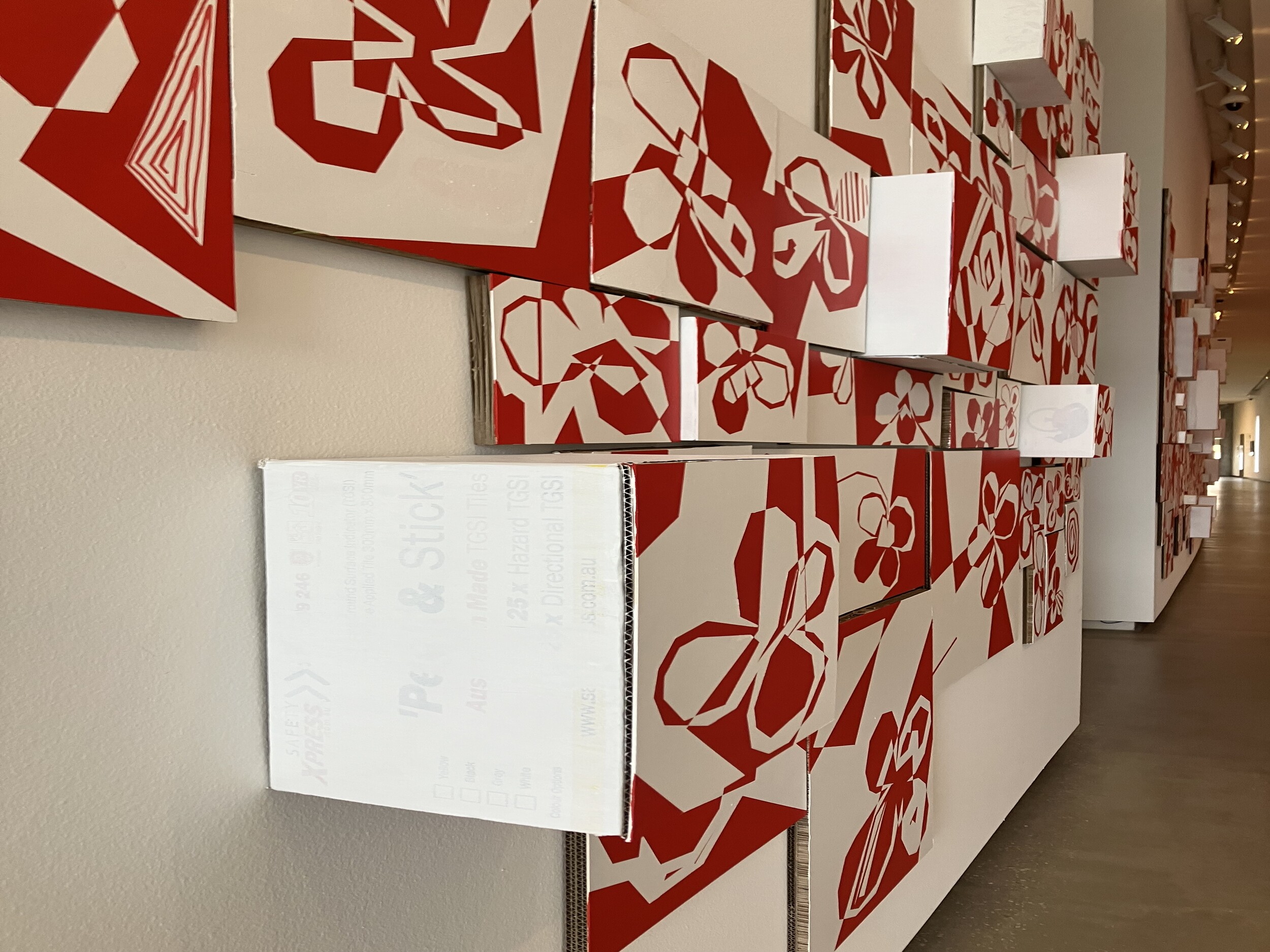

Installation view of Rose Nolan, To Keep Going Breathing Helps (circle work), 2016–17, acrylic paint, hessian, embroidery thread, steel, Velcro, 420 x 600 cm, TarraWarra Museum of Art. Photo: Ella Howells.

Rose Nolan: Breathing Helps

Ella Howells

The rammed earth fortress that is TarraWarra sits atop a steep hill; a sandcastle scaled-up. Entering requires scaling the incline to reach its red (and white) heart: Rose Nolan’s latest career survey exhibition, Breathing Helps.

Breathing helps: breathe in, hold, breathe out. A box breath. When breathing fails, dissecting everyday detritus with a box cutter helps. Nolan is known for her use of boxes as the material basis for many of her works, assembling, dissembling, and denuding them, often leaving their original purpose recognisable so their transfiguration is overt. The survey begins by contrasting two works in this vein, both with brand logos still half-intact. The first is Low-down White Trash Work (1995), which leans nonchalantly against the wall, representing the series of cardboard Constructed Works she initiated during her 1990s Store 5 era. It protrudes towards a smaller 2023 Working Model, composed of concertina-sliced and stacked homeware boxes with a diaristic Marimekko logo peeking through a blotched veil of thin white paint.

The boxes’ difference in pallor is what interests me here: the warmth of the White Trash Constructed Work (1995) against the stark, cool white featured throughout the rest of the exhibition may be the sepia result of the cardboard maturing, or maybe the rosy lens of nostalgia is built in. The first time I saw and loved this work, its rigid proboscis was grazing the dirt floor of Guzzler, the Rosanna gallery-cum-shed, in 2022. This was a time where Nolan was showing at a new crop of DIY galleries that have now all dried up as quickly as they sprouted, their proponents propelled to (arguably) greener pastures.

Reviewer’s personal instagram post of Low-Down White Trash Work, 1995, cardboard, glue, oil paint, plastic tubing, staples, 109 x 46 x 113 cm, Guzzler, 2022.

Much has been said on the tendency of Melbourne’s commercial and public institutions to overlook their local constituents, causing fellow artists and artist-run spaces to enact that recognition instead until they’re overpowered by obscurity or the overseas pull. Even back in 1998, when Andrew McQualter and Sandra Bridie discussed the legacy of the artist-run space Store 5, they said that:

Over the last five to ten years, artist-run spaces were seen as a stepping stone along the career path of artists, now they have assumed a role that is more on par with that of the commercial scene and the art institution. They still represent the work of emerging artists, but also that of more established artists, the boundaries are less clear.

For some, this is not necessarily a bad thing. Some scenes thrive on neglect. Art made from rubbish has to retain its dirty integrity somehow.

In Nolan’s case, this agility is part of what draws new people into the fold of her practice. She’s just as likely to show at a lowkey DIY space like Hyacinth as she is at a commercial gallery or institution, and the essence of the work never loses its shape due to her sensibility for viewing exhibition spaces as extensions of her studio. For the survey, she created a scale model of TarraWarra’s galleries to inform her works’ placements. This level of investment in the artistic ecosystem at every level makes me believe the rumour I hear that she was present for every single day of the install.

Installation view, Rose Nolan, Big Words (Not Mine) — Transcend the poverty of partial vision (floor version), 2021, Big Words (Not Mine) – Read the words “public space”…, 2013, and Low-Down White Trash Work, 1995, TarraWarra Museum of Art. Photo: Ella Howells.

Opposite the constructed works, in situ and in essence, is a carpet series inlaid with the all-caps quote: “TRANSCEND THE POVERTY OF PARTIAL VISION,” only legible in perpendicular mirrored panels fitted to the gallery’s wall. The phrase, and many others contained in Nolan’s ongoing body of Word Work, is borrowed from Ian Burn. In his 1990 essay “Glimpses: On Peripheral Vision,” Burn discussed how artworks containing words and letters create friction between seeing and reading. Here, his instruction is repeated as an incantation. I also received instructions from the attendant to remove my shoes before walking across the rug. It’s 100 percent New Zealand wool. It’s soft, but the inlaid text is too crisp underfoot. In contravention of the folk-approach Nolan has taken with the surrounding works—each carrying evidence of a hand-wielded box cutter—it seems depersonalised. I wonder whether the carpet will become collaboratively stained by the end of the exhibition’s runtime or whether someone is dutifully vacuuming it—perhaps with a Henry, to match the red wool, or with a Rug Doctor to resuscitate the white letters. Following the carpet’s instructions now, I lift my head in an attempt to TRANSCEND. Above, hessian bunting is adorned with more words, this time from 2013: Big Words (Not Mine) – Read the words “public space”… Having removed my shoes, the public and private spheres feel suddenly converged, and the barrier between them is now as thin as my socks. Fine. I put my boots back on to continue.

TarraWarra’s central gallery is cavernous. What you see immediately is what you get. This leads to an intentional yet unfortunate sense of seeing most of the exhibition at once. The whorled panels of To Keep Going Breathing Helps (circle work) (2016-17) are suspended between the white ceiling and the grey polished-concrete floor, glitching like lassoed pixels when viewed whilst walking. Close up, these pixels reveal the organic humility of their hessian substrates. On their verso, each disc shows that paint has bled through its weave, as though oozing from their precisely cut edges, then been stitched onto a white grid of bandage-like strips. Velcro clasps each large gridded panel together so it can hang in a spiral on a customised rig. It’s all quite orderly and medical, like hospital curtains that are whispered behind, and, at certain moments, are possible to glimpse through. The sheer volume of effort involved in creating these hessian panels is overwhelming, which gives the adjoining room’s screen-printed photographs of Nolan producing them a sense of gravitas—especially as she’s juxtaposed herself with Jackson Pollock working in his studio. The press release confirms that these interspersed photographic stripes are a comment on gendered creative labour. I admire the convivial machismo of displaying his chaotic, piss-soaked workmanship alongside her relatively methodical process, and irrespective of these feminist overtones, the blurred, flipbook stop-motion effect is fascinating.

Rose Nolan, Immodest Gesture #3, 2025, ink, archival paper, cardboard, 80 x 120cm, TarraWarra Museum of Art. Photo: Ella Howells.

The name of the circle work, To Keep Going Breathing Helps (circle work) (2016-17), is lifted from a snippet of speech Nolan overheard. Found objects and found words. It belongs to a series titled Big Words (not mine), which almost absolves Nolan of being a conduit. Don’t shoot the messenger. With many works from this series lining the perimeter of this room, the effect is that of a word-salad spinner, where words are flung at the wall to see what sticks. Many of these works borrow from the language, literal and visual, of product design as much as they do from Russian Constructivism. A process of obfuscation occurs through the layered cacophony of meanings, ultimately to arrive back at the superflat surface itself, demonstrating how, as Susan Sontag says, “the greatest artists attain a sublime neutrality.”

There’s also a psychoanalytic reading here. The survey’s curator, Victoria Lynn, cites psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster’s latest book, On Breathing (2025), as context for how the exhibition speaks to our cultural era. Webster asserts that breath “brings us back to the foundational tenet of psychoanalysis: say anything.” She also mentions how, in their attempt to find meaning through psychoanalysis, Freud’s collaborators Sándor Ferenczi and Otto Rank (both explorers of breath and anxiety) wanted to “rip open the box.” This was apparently followed by a moment when, as Webster writes, “Freud was like, ‘all of you, just stop,’ and he got really angry about it. He felt, ‘you can’t raid the lock box. You’re not going to reach the bottom. The bottom’s always a false bottom.’” This doesn’t deter me from contemplating the proverbial box and its capacity for holding meaning though, even if I can’t observe all its contents. In Nolan’s Flat Flower Work (2004–25), painted and fragmented boxes continually grow in number over the years with each installation, creating a visual kaleidoscope of symbolic concealment. The effect is dizzying. I empathise with Ferenczi and Rank when I’m inside the exhibition: I’m surrounded by linguistic commands that appear to hold meaning—even inadvertent meaning by virtue of including the occasional logo on an iPhone box, for example, but any attempt to pry deeper is rebuffed, and I’m left with myself and my breath. Sublime neutrality?

Installation view, Rose Nolan, Flat Flower Work, 200–25, acrylic, cardboard, dimensions variable, TarraWarra Museum of Art. Photo: Ella Howells.

Recently, Nolan’s gallerist made an announcement via a vividly recounted interview in The Age. The eponymous Anna Schwartz Gallery will, after one more show by Nolan’s late mentor John Nixon, become Anna Schwartz Projects. This reflects a broader shift towards the fast-paced immediacy of events, talks, and other ephemeral interventions where you “just had to be there.” Having forfeited sublime neutrality, I suppose one must hit the accelerator and avoid sitting still at all costs. I pay the gallery a visit, on the last day of Nolan’s Word Work exhibition there, running (almost) concurrently with the TarraWarra survey. Last time I saw these walls so red, they were painted with references to Gaza and Israel by a blindfolded Mike Parr, after the performance that marked the end of his and Schwartz’s thirty-six-year professional association. The end of an era is nigh, and even the words chosen for these works, again from Burn’s pen, seem prescient, purposefully or not: “ALMOST OVER BUT NOT QUITE,’‘ENOUGH’, ‘NOW WHAT/WHAT NOW.” The writing is literally on the wall. Or on your embroidered Alpha60 outfit purchased from the TarraWarra gift shop.

Installation view, Rose Nolan, Word Work, 29 August – 11 October, 2025, Anna Schwartz Gallery.

There are many moving parts, orchestrated and maintained consistently over the span of decades, that go into creating a powerhouse figure such as Rose Nolan. Lynn has, in this case, shared her curatorial responsibilities with Nolan, saying that the artist has, “in many respects, curated her own exhibition.” In electing to use this survey opportunity to create a new project, Nolan actively approaches it as she would a solo at Anna Schwartz Gallery, or as an extension of her current studio.

Artists having this level of control over installation and curation, particularly in a show of such scope and involving a first-time collaboration (here, with choreographer and performance artist Shelley Lasica), pose a unique challenge to viewers: get with the program. Due to this, viewing the TarraWarra exhibition as a survey in the conventional sense might leave those who are seeking fulfilment of this chronological and context-rich premise wanting, as Nolan’s oeuvre isn’t necessarily showcased with a balanced vision. Rather, Nolan’s intimacy with her own work has allowed her to extend her creativity and generosity elsewhere, by extending her practice collaboratively, implementing custom installation, and placing works in unconventional configurations that are often generative, or at least keep us guessing, imagining her wry smile.

Ella Howells is a writer, artist and arts worker in Naarm/Melbourne.