Drawing inspiration from two fertile periods of art activism in Australia, one from the 1930s to '50s and another from the late 1970s to '80s, the exhibition State of the Union at the Ian Potter Museum of Art is framed around the relationship between artists, trade unions and the labour movement. In recent years there has been a burgeoning literature on the interrelated issue of artistic labour, as well as a growing number of art collectives contesting issues related to their own labour, and the question of whose labour supports the art world. Prominent examples include the Precarious Workers Brigade, Gulf Labor, Working Artists and the Greater Economy, Occupy Museums, Art Leaks and Occupy Wall Street Arts & Labor. The intensified interest in the relationship between art and labour has no doubt arisen due to the pressure that neoliberalism is applying to the vast majority of people world-wide. The last three decades of deregulation and privatisation have reshaped work for almost everyone in the industrialised world. The percentage of people in contingent employment has risen steadily in industrialised countries (affecting both workers in in low-end service roles and high-wage occupations) and has maintained its stronghold in developing ones. Today's employment conditions, shaped by an explosion of casual, temporary and part-time arrangements in the West, are far removed from those of the Fordist-era in which workers could expect incremental wage hikes and job security in return for increased productivity and industrial stability. In much of the recent theoretical discourse surrounding artistic labour, artists have been interpellated as the paradigmatic worker under these precarious conditions. The curator, Jacqueline Doughty, situates the exhibition State of the Union within these debates by calling for a breakdown of the distinction between artistic labour and other forms of labour, so that artistic labour might be more fully recognised as work.

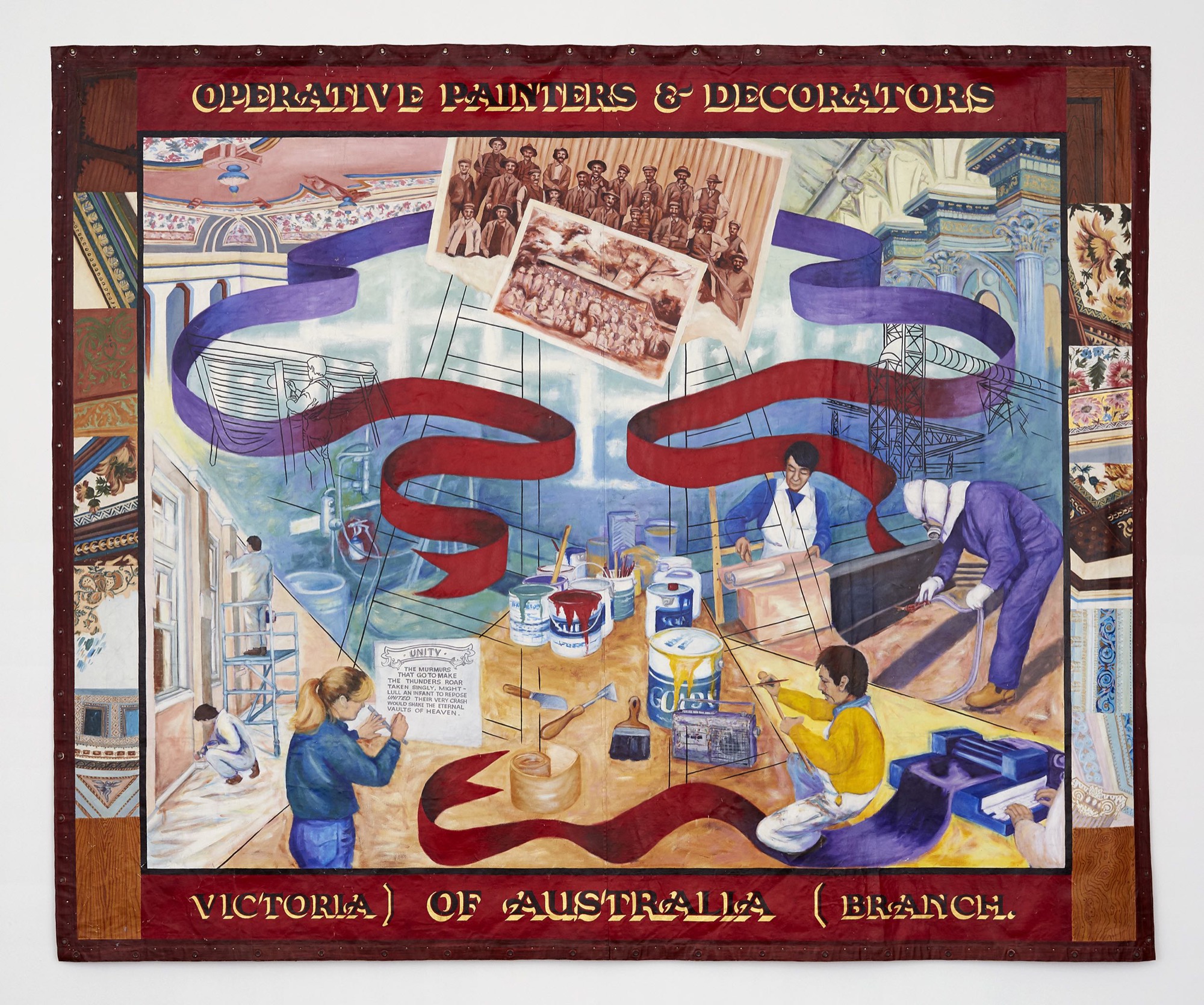

Although the exhibition has no hard and fast structuring device, such as proceeding along strict chronological lines, certain affinities emerge in a number of galleries. This is most pronounced in the first, which is dedicated principally to protest banners. It begins with two large-scale banners, one made in 1915 and the other in 1988, representing the Operative Painters and Decorators Union of Australia. Upstairs, to the left, we encounter a gallery focused primarily on the work and activities of the Art and Working Life program. A number of works in this section also broach the important topic of women's work. Shedding light on the under-acknowledged period of Australian art activism that was centred around the Art and Working Life program is one of the most significant aspects of the exhibition. The Media Action Group was founded in 1977 by a group of artists and academics, including Ian Burn, Michiel Dolk, Kieren Finnane, Mary Kinney, Nigel Lendon, Ian Milliss, Anne Sutherland and Terry Smith to develop alternative media and agitate around cultural and political issues. In 1981 the group was renamed Union Media Services; its directors were Ian Burn, Ian Milliss and Lesley Pearson and its focus turned to working on trade union publications. Union Media Services played a major role in the Art and Working Life program, which was created in 1982 by the Australia Council for the Arts in partnership with the Australia Council for Trade Unions to encourage art both by and for workers in collaboration with trade unions. A number of works, posters, publications and documents show the activities of Union Media Services and the Art and Working Life program during the 1980s. Rotating mechanically in an outmoded slide projector, Ian Burn's activism is, in part, represented by a grainy pedagogical slide kit that he made in 1984 to promote the Art and Working Life program to trade unions. Burn was a key advocate for the Art and Working Life program and State of the Union appears to have drawn inspiration from an exhibition that he curated in 1985 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, titled 'Working Art: A Survey of Art in the Australian Labour Movement in the 1980s'. The exhibition was the first national survey of projects from the Art and Working Life program and one of Burn's aims through it was to democratise the context of art by undermining the conventional separation between the creative strategies being used in the labour movement and those of fine art.

'It's not a bad job': Re-presenting work (1984) is a compelling political photo-work that State of the Union brings to renewed public attention. Made as part of the Art and Working Life program by Julie Donaldson, Helen Grace and Warwick Pearse, it is presented on cheap, portable laminated cardboard panels overlaid with black and white photographs of workers, images of workplace injuries, advertising and text. The work shares marked similarities with political photography projects from the 1970s, such as the agit-prop panels by the British feminist photography collective, the Hackney Flashers (with whom Grace collaborated for a brief period from 1975 to '76); and in both its form and content (the handling of workplace injuries and the everyday violence experienced by workers under capitalism), The Health and Safety Game (1976) by the American artist, Fred Lonidier. Coincidently a number of Lonidier's works were shown at the Victorian Trades Hall in 2017 as part of Nicholas Tammens' ongoing curatorial project, 1856, which is also centred around issues of labour. 'It's not a bad job': Re-presenting work, is part of a lineage of political photography that can be traced back to the worker photography movements of the 1920s and '30s. While its subject matter addresses factory work, workplace health and safety, the ideological function of advertising, reproductive labour and the role of photography within the workplace, its form looks much like a workplace bulletin board. This style of arrangement, which re-emerged during the 1970s, can be traced back to the wall newspaper, which was a type of makeshift bulletin board used in factories in Soviet Russia and in Communist East Germany as a leftist alternative to the mainstream press. 'It's not a bad job': Re-presenting work uses photography as a socially engaged form of political pedagogy. In its original context, it sought to reach out beyond the art world; it was first shown at the Workers Health Centre in 1984 and then toured various workplaces and unions. Showing works in non-art venues, such as unions, trades halls and community centres was an activist strategy used across a number of countries during the 1970s and '80s. The work builds on these traditions of political photography through its implication of photography itself as a form of power, drawing attention to the fact that it is most often used in the workplace in the form of surveillance and control.

Supported by a raw wooden plinth in the final gallery, two iPads allow artists to log their pay grievances in a work called, ARTSLOG (2018) by a Melbourne collective, the Artists' Subcommittee. Both the Artists' Subcommittee, and the curator, Jacqueline Doughty, call for artistic labour to be unionised. While contemporary art is a large global industry with massive inequalities, there are problems with the demand to unionise artistic labour. Firstly, artistic labour does not strictly conform to the capitalist mode of production, but instead has a dialectical relationship to it. This is because under capitalism, production is subordinated to capital through the commodification of labour and its exchange for capital. According to Marx, this occurs when workers are compelled to sell their labour-time to a capitalist who profits from their work. In contrast, artists do not sell their labour-time as a commodity. Instead, artworks enter the market and become commodities when artists sell their artworks. Further, a work of art's value is based primarily on the artist's reputation and not on the amount of labour-time the artist puts into them. This, and the fact that artworks are largely unreproducible, separates art from other forms of commodity production and from wage labour. While it is true this separateness from the capitalist mode of production, which is still fundamentally structured by wage-labour, can be used to justify exploitation, the danger in calling for artistic labour to be regulated is that this would simply subsume it more fully under capital. In addition, generally speaking there are class tensions between artists and wage labourers that their conflation tends to obfuscate. Admittedly, artists' fees are not the same as wages, and it is certainly positive to put pressure on art institutions to pay them and to make transparent working conditions in the art world. However, artists' fees at their current rates do not go anywhere near covering an artist's cost of living. For this reason, a guaranteed income or social wage unattached to productivity, as well as addressing the unaffordability of housing, would be a better way of supporting artists than the payment of artists fees. Unfortunately, art practices that foreground issues of remuneration still operate within a competitive capitalist system in which supply outstrips demand, and while they attempt to intervene in capitalism's accelerating contradictions they do not fundamentally disrupt its logical conditions—those of wage labour.

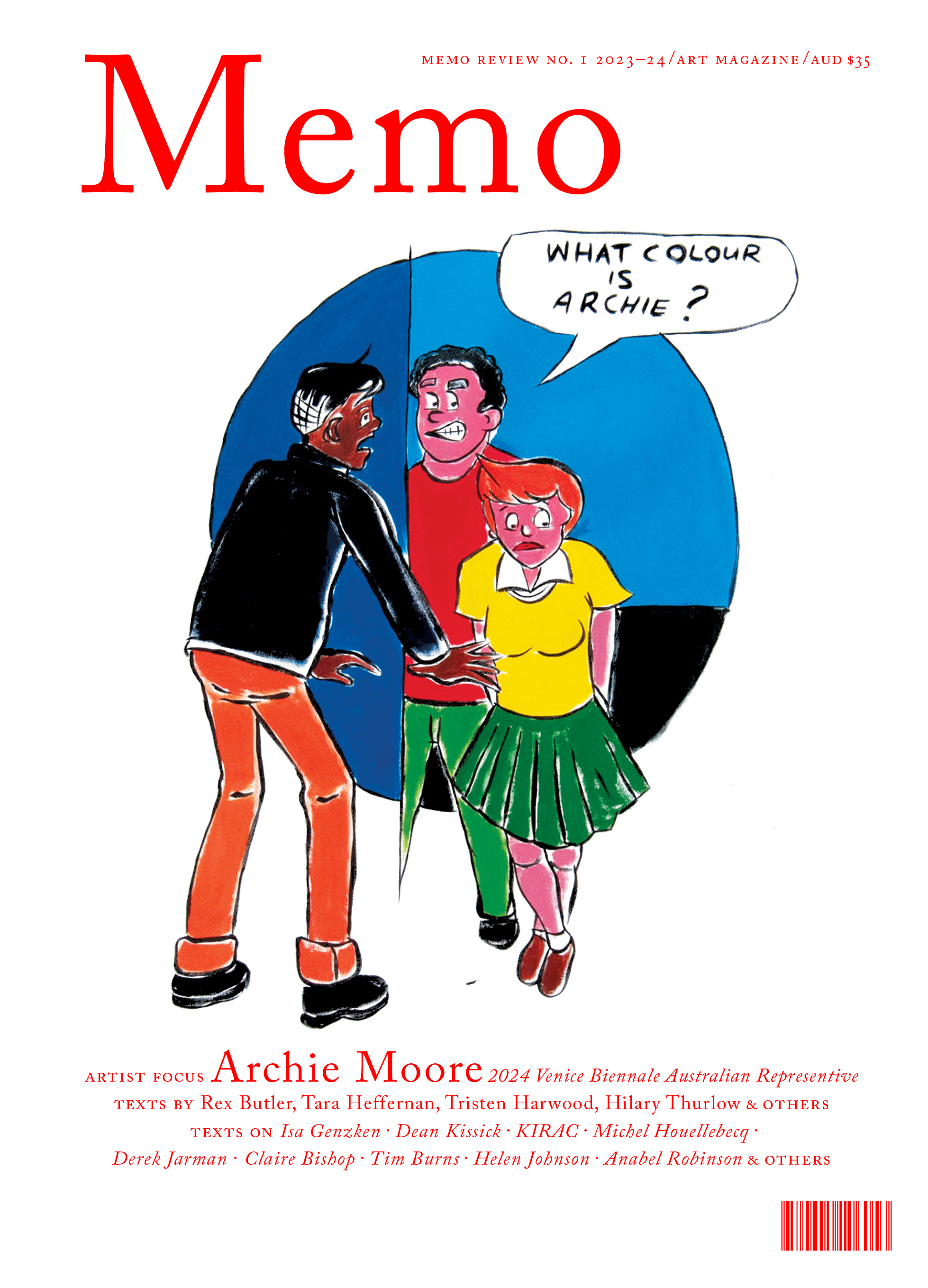

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

The exhibition blurs high and low cultural distinctions by bringing together a wide variety of materials that encompass both art and non-art objects. These cover an extensive period of art history (the twentieth and twenty-first centuries) and take a multiplicity of approaches to both art making and art activism. This produces an exhibition where the works and materials often sit beside each other uneasily. There are a number of additional tensions within the exhibition. One of these is the contrast between the documentation of grassroots activism and the relatively high budget, international film and video works. This, in addition to the fact that there are only three international works in the exhibition, leads one to question whether their effect might be one of legitimation and consolidation within an international art world context. If the works do in fact function in this way, then any attempt at the democratisation of art by dissolving the distinction between art and non-art within the exhibition must be deemed unsuccessful. Another tension is between the works that think more critically about the politics of aesthetic form, such as The Battle of Orgreave (2001) by Jeremy Deller, and those that use traditional modes of representation. While these tensions between different styles and positions may have been intentional, a more focused exhibition could have been produced by honing in on a specific period or approach.

State of the Union presents a salient examination of the issue of labour and an opportunity to debate the current working conditions of artists, but to structure the exhibition specifically around the topic of unions today seems somewhat problematic. Firstly, the position of unions is currently one of crisis. Union membership in Australia has fallen for more than three decades. From being a world leader in terms of union membership, Australian unions have experienced one of the most rapid declines of any Western country. This decline is highlighted by the fact many of the contemporary artists in the exhibition take an archival approach in their exploration of the topic, re-examining past events in times when unions had more power. Focusing on unions also brings up the issue of the individuals and groups that unions have historically excluded; an important example in Australia is the slavery of Indigenous people, which was taking place right up until the 1970s. While the catalogue essay does note the decline of trade unions, the question still remains of whether focussing on them now is the most well-timed way of structuring an exhibition on the topic of labour. Importantly, though, this problem may generate critical thinking about the current role of unions and how they might be linked to a broader political movement.