I am hesitant to say that I am employed. Although to say I am unemployed is also incorrect. I do not have a job to go to, but I do have four email addresses — 1 personal, 3 professional — and from the moment I wake to the moment I go to sleep my mind is preoccupied with work. The question is, at what level of productivity am I working? I check emails when I get up, go to my studio and write inefficiently while generally procrastinating by means of social media and online shopping, and at night I sit in bed, scrolling Instagram while chastising myself for not reading or watching some foreign film that will improve my neural paths. On top of all this, my days also revolve around applying for jobs, jobs that will invariably take me away from my writing, the work that is really my ‘profession’. I am working to work: a tautology, if you like.

Unproductive Thinking considers the contemporary lack of division between labour and leisure, which is certainly exacerbated in the arts. In addition to a general decadence/discipline binary culture of food, wine and socialising at one spectrum and Fitbits, fun runs and ‘walking meetings’ on the other, arts workers must also attend never-ending exhibition openings, endless networking drinks and too many public lectures. Unproductive Thinking’s central focus is the artist, though there is food for thought for anybody even remotely engaged with contemporary society.

Curated by James Lynch, the exhibition is a breath of fresh air for Deakin University Art Gallery, which, before Lynch’s appointment, generally lacked a deep engagement with contemporary art. Indeed, Deakin should be thankful to have Lynch who, thanks to his years as Collections Curator at MUMA as well as his experience as a practising artist, appears determined to bring the gallery up to a level that entices people to make the trek out to Burwood. This exhibition is a promising start. Using a cross-generational model to present the idea of the overextended mind and soul of the artist, Lynch has also used three sites to stage the exhibition – the galley, the campus gym and the library – in what is perhaps a wry nod to the renaissance notion of the well-rounded human comprising of a healthy mind, body and soul.

Allow me to begin by returning to the tautology of working to work. The first piece in the exhibition could easily go unnoticed. It is a page from the mX newspaper from May 16 2013 that has been taped against the window of the gallery. The page contains an ‘advertisement’ of a stock image of an orange paid for by Jessie Buillivant and is called Giving Away Something that is Free. The image was free for the taking, most likely plucked from a Google search, while the mX newspaper, too, was free of charge. However, the irony is that Buillivant paid to give away what was already free: she worked for the sake of working without really adding value to the original image.

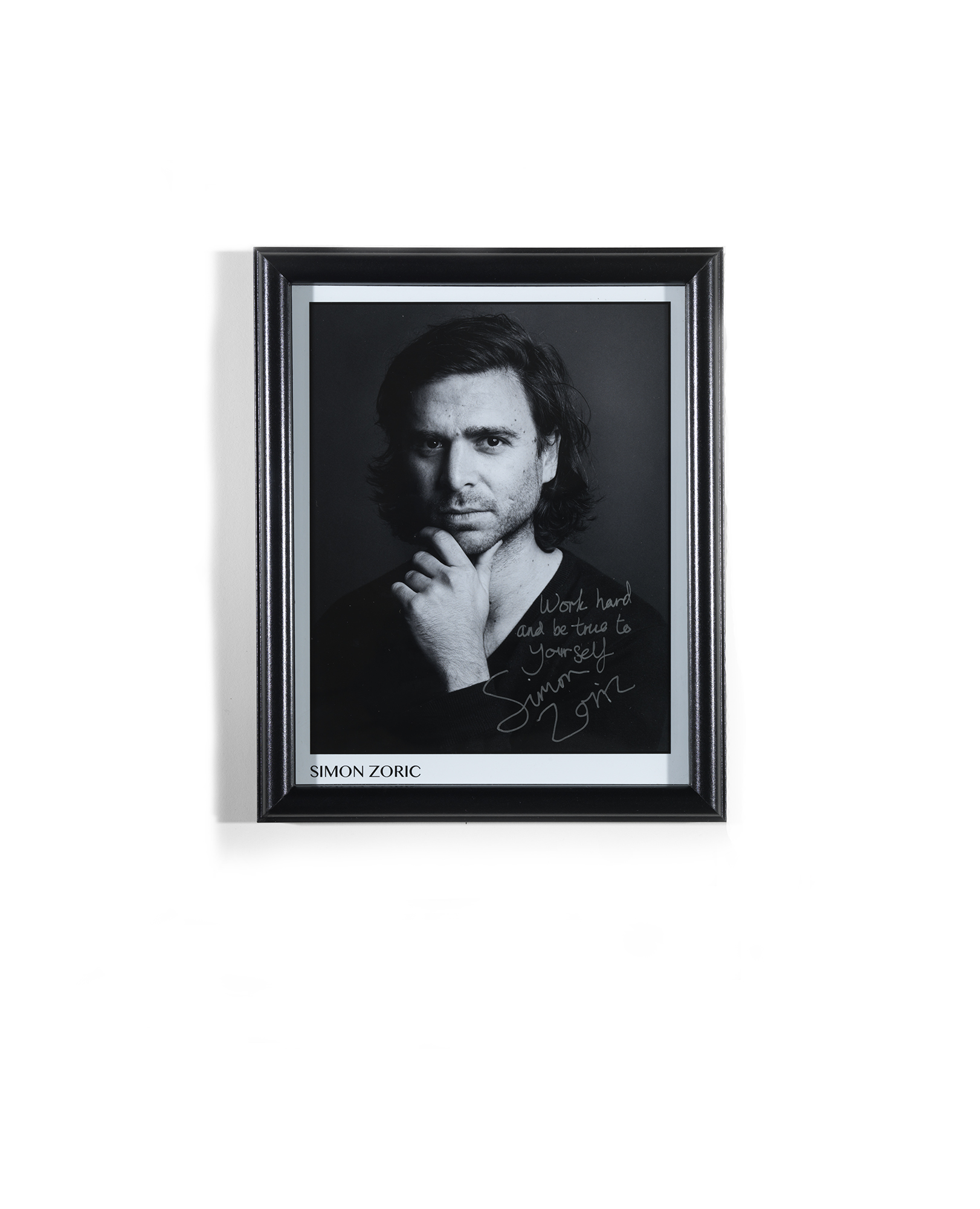

Elsewhere, the work of Simon Zoric is rife with humour and unease. Indeed, the exhibition’s hero image of Zoric’s cool, calm and collected headshot — The Finest Actor of our Generation (2016) — is at odds with the immense anxiety of What’s Your Beef Guv’nor (2007), a familiar butcher’s chart that labels each beef cut with all the common failings of human beings, be that ‘eat bad food’ or ‘waste time on the internet’, and From the Desk of (2013) a letter to the NGV requesting that they acquire one of Zoric’s pieces that quickly digresses into ramblings of Zoric’s general anxieties. Anybody familiar with Zoric’s oeuvre will recognise the pendulum swing between absolute egocentric facades and the fear of exposure that is at the core of his image-making. With the constant need to be switched on comes a constant feeling of self-doubt (barely) contained under a calm exterior.

Several instructional works on paper from Ian Milliss — the artist best known for his falling out with Ian Burn, but who should also be recognised as one of Australia’s most interesting conceptual artists — sit quietly opposite Zoric’s pieces. It is a genuine joy to see these works. All dated 1970, they were created at a moment when Milliss was really beginning to interrogate the meaning of the institution. These works plant the seeds for Lynch’s exploration of time and process in the exhibition. I also can not help but think there is a beautiful parallel to be made between Zoric’s satirical From the Desk and a genuine 1971 letter written by Milliss to the judges of the Young Contemporaries art prize that is held in the NGV archives. In this letter, Milliss demands an award, writing ‘it’s about time I was given a prize of some sort’.

Elsewhere, action and repetition play out as age-old processes of the procrastinating artist in Eugene Carchesio’s doodles and cardboard sculptures, Rob McHaffie’s watercolours and Elyse de Valle’s marble sculptures. One gets the impression that these pieces reflect a mediative respite that is all too commonly pushed to the wayside. But process is most poignantly explored in Lauren Burrow’s Lose the Language (2015). Over a series of nights Burrow went to sleep with slabs of clay, which then became imprinted with the creases of her skin. She then fired and glazed these slabs before scattering them around the gallery wall, about a foot from the ground. The metaphor of working in one’s sleep is pertinent to the endemic feeling that shutting down is all but impossible in a society of 24/7 connectedness.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

In the campus gym, Laresa Kosloff’s video Personal Trainers Demonstrate (2017), featuring two personal trainers repeating actions choreographed by the artist, is nothing short of comical. Certainly, the concept of empty actions performed by people who, in their professions, push people to constantly succeed and self-improve is perversely satisfying. Kosloff’s exploration of the irony of ‘doing nothing’ is rounded out by I Can’t do Anything (2015) back in the main gallery. The work is a simple video of people of various ages repeating the same line — ‘I can’t do anything’ in Italian or English (the video was filmed during a residency in Italy). Indeed, the notion of ‘nothing’ has been grossly exaggerated under the pressures of late capitalism. Because simply by being in the video, by uttering this line, by existing, these people are doing something. We can then interpret Kosloff ’s idea of ‘nothing’ as not doing anything that is considered of value in an era of quantification and outcomes.

I want to conclude with the artist I began with. Jessie Bullivant’s In the Event of Fire (evacuation) (2017) is perhaps the most poignant work by virtue of the fact that it is not present due to bureaucratic rules. Bullivant proposed a fire drill in the gallery that would force students and employees to stop what they were doing – essentially imposing a moment of cease work. However, the drill was not allowed to happen due to OH&S regulations. Anybody who has ever worked in an administrative organisation such as the university will cringe to think of the hoops that the artist and curator would have jumped through only to be finally told that their efforts and time were for nothing. And so while Bullivant’s goal was to create a time of meditative nothingness from a simple gesture, she invariably exerted maximum effort for zero outcome.

Lynch sums up the complexities of the current ‘condition’ in his essay for Unproductive Thinking. He writes, ‘immersed in a sea of endless data, there is very little time remaining to reflect.’ I would add to this observation that reflection is generally viewed as a waste of time when outcomes and numbers are what reap the reward. However, in drawing our attention to the economy of constant work and its best friends anxiety and fatigue, Unproductive Thinking succeeds in coercing its viewer into a rare but welcome moment of contemplation.

Amelia Winata is a Melbourne-based arts writer with an Honours degree in Art History. She is also the Sub-editor of un Magazine, a Research Assistant and an Arts Administrator.

Title image: Simon Zoric, The Finest Actor of Our Generation, 2016, autographed, inkjet print, framed, 20 x 25 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.)