Discovering Dobell / Dobell’s Circle

Victoria Perin

TarraWarra, clearly reaching for the best of both worlds, likes to market itself as 'privately funded, public art museum'. As a charitable not-for-profit company, the museum is sponsored by the Besen Family Foundation, while also receiving project-based public funding. Twinned to a vineyard, it balances out Melbourne's other favourite weekend getaway, John and Sunday Reed's publically-bequeathed Heide Museum of Modern Art. The three current exhibitions, Discovering Dobell, Dobell's Circle, and the additional Selected works from the TarraWarra Museum of Art Collection, draw heavily on artworks collected personally by the Besen family, and works collected since TarraWarra's founding in 2000.

Relevant to the showc_ase of 'coll_ection highlights', it is galling that TarraWarra's relatively small collection is not completely available for viewing online. The private origins of TarraWarra (and Heide, whose collection search is equally terrible) means that we exclusively conceptualise such places as gifts to the Australian public. For that perhaps our expectations of access are lower. After all, it is poor taste to look an art-donor in the mouth. Yet even if we gloss the public backing, and the cultural gifts made to them with substantial tax-breaks from the Australian Government, these institutions hold artworks of national importance that are a part of our collective cultural heritage. State and national institutions are expected to rapidly prioritise their digital access to collections. With public money comes public responsibilities. TarraWarra, if they don't already, should have the task of collection digitalisation prioritised in the near future.

Discovering Dobell highlights a favourite artist of the Besen's, whom they began collecting in the 1950s. The William Dobell we are invited to discover in this exhibition is coloured by 'Besen's Dobell', with highlights from major lenders added for heft and breadth. Discovering Dobell is small, wholly contained in the Museum's first room. Visitors will typically recall this room being used to display an artist's 'early works'. So to find Dobell's early, middle and late period gathered together feels condensed. It is justified though as, contrary to his big reputation, Dobell's works are petite. They oscillate between a small intimate scale (sketchbook size, or boards that fit in the crook of your elbow) and large three-quarter length portraits, as featured by the bow-lipped The Student (Warren Stewart) (1940), Dame Mary Gilmore (1957), Helena Rubinstein (1957), and the cursed Mr Joshua Smith (1943), in a heavily restored, heavily compromised condition. These four works are the room's consciously 'big' pictures, which the artist clearly intended for public display. These are the Dobell paintings everybody recognises, and are coming to see. They hover in the Australian cultural subconscious in a way not dissimilar to the portrait of Mary Gilmore hovering in the background of the Australian $10 note.

So the job of Discovering Dobell curator, Christopher Heathcote, is to sell the private, small-scale works to a crowd coming with very different pictures in their mind. James Gleeson, in his beautifully intimate account of Dobell's work from 1964, sets up this problem immediately, informing his reader that: 'His largest things would be lost in the corner of a Pollock and some of his masterpieces would fit comfortably in a pocket.' He conveys his affection for Dobell's small-scale work, describing the New Guinea boards as 'tiny masterpieces of such exquisite delicacy'. There is enough in this tight first room to make the large Dobell's circle that follows appear over-generous with its liberal free-associations on Dobell's social group.

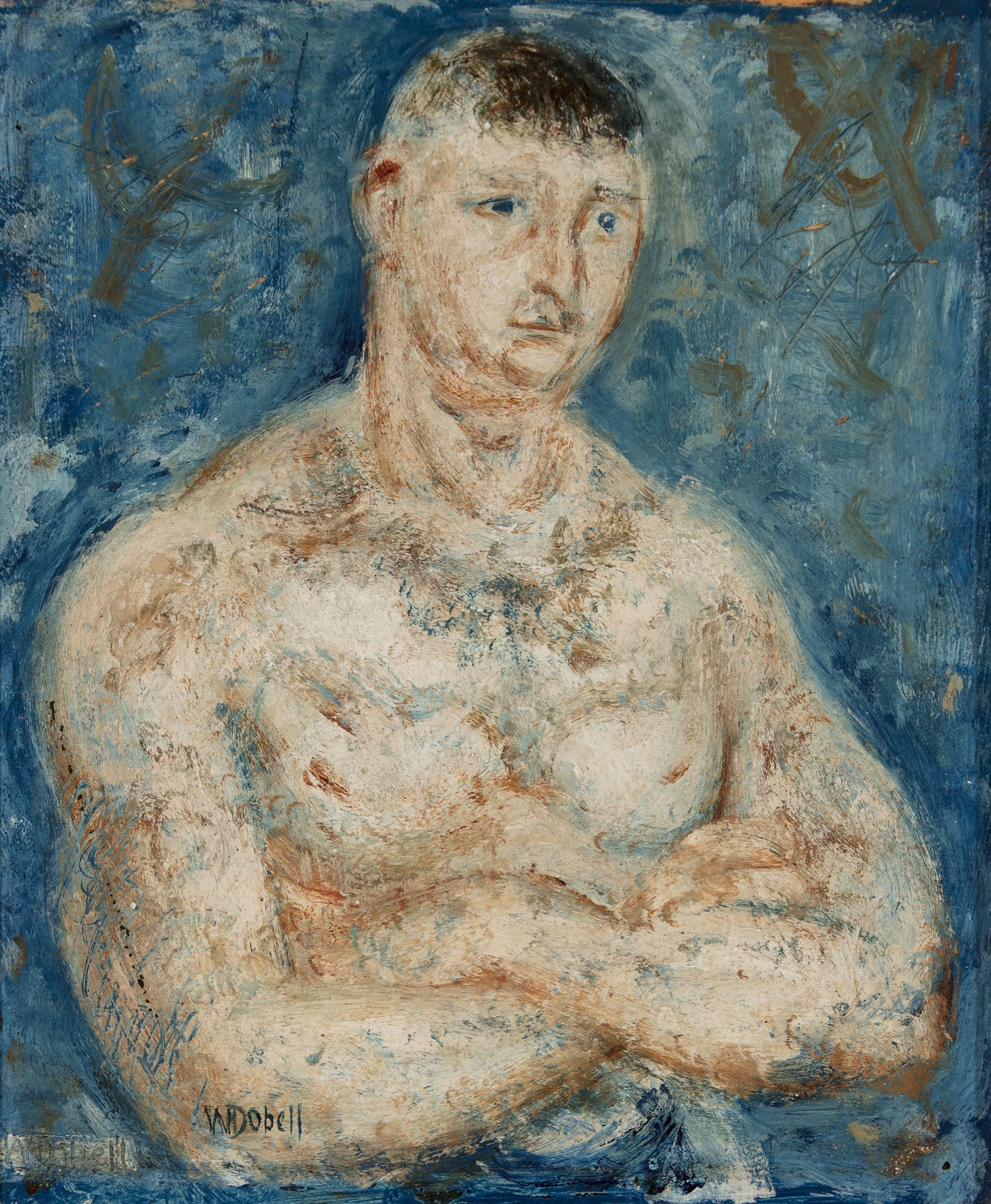

Gleeson and Heathcote give several clues for Dobell's peculiar painting technique, dominated by a tendency to highlight figures until they glare with an otherworldly translucence. The billy boy (1943), a glowing ball of a man with ghostly blue tattoos, is a typically strange depiction of a hyper-masculine working-class blagger. The white highlights are dragged around and around in circles until his facial features almost disappear. It is the confident outcome of a technique begun in London, featuring most notably in Mrs South Kensington (1937), which he picked up from staring at Rembrandts, Goyas, Van Goghs and Renoirs.

Dobell also took a long time to paint each image. In the copious comparisons between sketch and final work you can see that Dobell used that time to erase anything that was obvious or explicit. The small images and sketches frequently have more to say about Dobell personally. The men are handsomer, the women more down-to-earth, the London scenes are quiet with a sense of winter loneliness. The suprising study for The billy boy is a good example. It shows a crew-cut, muscle-bound hulk with sustainably more sex-appeal than the final work. The study shows an initial sensual attraction to the subject, while the finished piece smooths down the pecs and the shoulders into a warm character study (albeit of a 'coarse' member of the lower classes).

It is this same distancing effect that complicates Dobell's commentary on class in general. After three Archibald prize wins, Dobell was an in-demand portrait painter of noble elites. Yet his early years were spent chasing a Hogarthian cycle of London's poor cockneys. Unlike Hogarth, however, Dobell's feeling towards such people are too subtle for the contemporary viewer to read clearly. Heathcote writes of the famous portrait The Cypriot (1940, not on display), that 'Offensive paintings often lose their tone with the passing of time, because meaning fades as a society changes.' He suggests that the sitter, named Aegus Gabriell Ides, is posing as a 'cockney crook', a smooth criminal. 'A contemporaneous West London eye would further point out he is depicted during a break from a gambling session…' If this reading is correct, then indeed the tone has been lost by some viewers, quite markedly, as this is the same portrait that poet Clive James interpreted as a dark-eyed vision of Dobell's lover, 'A man who he had loved and seen asleep/The painter painted naked, a Greek god.'

As fitting with his ghostly technique, Dobell's social judgements are elusive, wary of being too vocal, too crass. While his initial observations are sharp and fast, as seen in the chattering collection of pen and ink sketches from Kings Cross, stereotype is detached as the painting drags along. Is The Cypriot a sly 'social type', or an intense portrait of a lover? The point of obfuscation begins with the artist. An extremely late image, Gentleman conversing with a prawn (1970) shows an older Dobell continuing a trajectory of ambiguity; a smoking geezer holding up the bar is seemingly painted with jewel-toned glazes and mist.

If it weren't for the paintings inspired by New Guinea (now Papua New Guinea), perhaps we could continue to look at Dobell as a beautiful painter with an introverted voice. What Gleeson termed 'tiny masterpieces' are highly-finished studies of larger compositions that Dobell did not have the confidence to complete (after exhibiting them he was discouraged by a critical attention). Collected on their own green-painted wall, they represent a seismic rupture in the curator's narrative. Dobell's distant gaze suits these deeply exoticised and abstracted studies. His two trips in 1949 and 1950 inspired radical experimentation, matching the artist for once with the modernist reputation he was popularly attributed. The wall text claims allusions to classical Greek art, Pablo Picasso and Henry Moore. But nothing here visually connects with the free-form Abstract-three figures, looking uncannily like Robert Klippel improvisations in a dark and verdant landscape. Here is where I needed the works in the next exhibition, Dobell's circle, to contextualise this departure. Unfortunately, limited to the TarraWarra collection, no such guiding focus is offered. Although Godfrey Miller, Justin O'Brien and Donald Friend could have helped illuminate the New Guinea visions (and all are present in Dobell's circle), the relationships drawn here are purely anecdotal.

Dobell's circle is a great idea for padding Dobell's slight images. However in practice it draws you further and further away from him. While each artist is justified by some connection to Dobell, the fast-paced comparisons reflect poorly on a few pictures. Margaret Olley in particular was looking sloppy beside Margaret Preston's bold eye for design. William Rose's linear abstraction appeared forced next to Godfrey Miller's shady agility. By the time I'd got to a display of Jeffrey Smart paintings from 1968, 1977 and 1984, I'd not so much discovered Dobell (who died in 1970) as I had been diverted and distracted from thinking about him, and his coy strangeness.

Victoria is commencing her PhD at the University of Melbourne. Her research concerns printmaking in Melbourne during the 1960s, 70s and 80s. In 2013, she was the Gordon Darling Intern in the Australian Prints and Drawings Department at the National Gallery of Australia.

Memo Review apologises for factual inaccuracies originally published in this review regarding the funding of TarraWarra Museum of Art. These have been corrected at the request of TarraWarra.

Title image: William Dobell, Abstract-three figures, 1960, oil on hardboard, 16.9 x 27 cm, Private collection © Sir William Dobell Art Foundation)